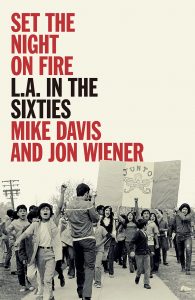

In Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, Mike Davis and Jon Wiener relocate the seeds of the radical 1960s away from New York City and Berkeley, California, centring the activism waged by African Americans, the Latinx community, Asian Americans, the LGBT community and women to ultimately redefine Los Angeles as the quintessential microcosm of paradigmatic change in America. This is a highly readable and scholarly volume that succeeds in giving renewed attention to the neglected voices of those central to the reconstruction of US society, writes Jeff Roquen.

If you are interested in this book, authors Mike Davis and Jon Wiener will be discussing it alongside Professor Robin D. G. Kelley and Dr Glyn Robbins for an online event organised by LSE Department of Sociology at 6pm on Monday 8 June. Information about the event can be found here.

Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties. Mike Davis and Jon Wiener. Verso. 2020.

Since the early 1800s, countless numbers of Americans have migrated beyond the Mississippi River in search of land, liberty and prosperity. One century later, during the Second World War, a new generation flocked to southern California to exploit expanding economic opportunities, the idyllic landscape near the Pacific Ocean and a superlative climate.

Since the early 1800s, countless numbers of Americans have migrated beyond the Mississippi River in search of land, liberty and prosperity. One century later, during the Second World War, a new generation flocked to southern California to exploit expanding economic opportunities, the idyllic landscape near the Pacific Ocean and a superlative climate.

In particular, many African Americans pinned their hopes on the Spanish-founded city named ‘The Angels’ to claim higher-paying manufacturing jobs and to escape racial discrimination. Their hopes would be largely dashed. Despite favourable US Supreme Court verdicts prohibiting both segregated seating on interstate buses and the use of restrictive covenants by real estate developers/communities to exclude minorities from purchasing homes in 1947 and 1948 respectively, the political establishment, which had largely aligned with or succumbed to the power of Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) Chief William H. Parker, presided over one of the most segregated and racially oppressive cities in the United States (9).

In the insightful and comprehensive new monograph Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, Mike Davis and Jon Wiener brilliantly relocate the seeds of the radical 1960s away from New York City and Berkeley, California, centring the activism waged by African Americans, the Latinx community, Asian Americans, the LGBT community and women to ultimately redefine L.A. as the quintessential microcosm of paradigmatic, ideological change in America.

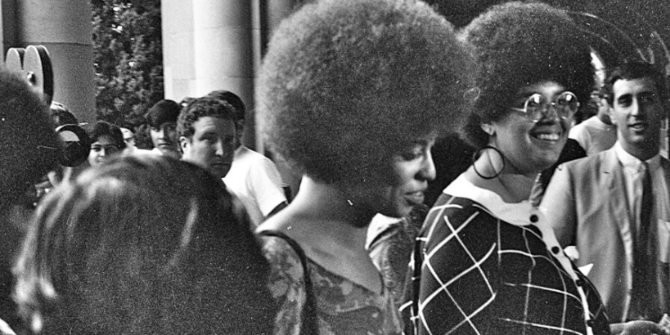

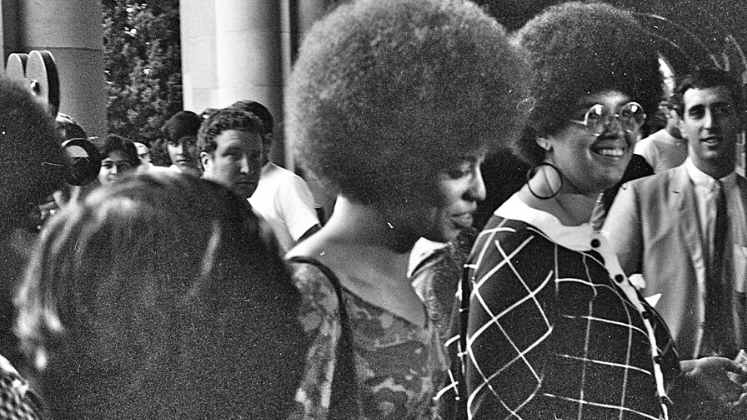

From the pages of their highly readable and scholarly volume on the origins and impact of radical activism in southern California in the 1960s, including essays on Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam (Chapter Four), the rise of the LA Free Press (Chapter Ten), the Watts Rebellion of 1965 and the ensuing cultural revolution of the ‘Watts Renaissance’ (Chapters Thirteen and Fifteen), the plight of Communist Party activist Angela Davis (Chapter 27) and the development of Chicano/Chicana identity and politics (Chapters 31 and 32), Davis and Wiener succeed in giving renewed attention to the neglected voices of subjugated minorities central to the reconstruction of society.

Separate and Unequal in Los Angeles: Mobilising for Fair Housing

Through Chapters Five to Seven, Davis and Wiener paint an effective and searing portrait of the stark inequities in housing between white people and the minority population. As a result of being denied low interest rate loans from the Veterans Administration (VA) and the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) as well as access to new housing developments, most African Americans, who had largely been relegated to subsistence-level wages, were restricted to living in poor neighbourhoods in the southern end of the city.

After successfully campaigning to open an all-white housing community to a Black physicist, Robert Liley, and pressuring the transportation industry to adopt equal hiring practices, the L.A. chapters of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the United Civil Rights Committee (UCRC) protested and filed a lawsuit against real-estate mogul Don Wilson for developing segregated housing for black people in Compton and building upscale residences in areas exclusively for white people. In response, the California Real Estate Association (CREA), all-white Citizens Councils and white Christian evangelicals formed an alliance, rallied for the ‘right’ to self-govern their communities and managed to gain statewide support and the adoption of Proposition 14 in November 1964 – a referendum essentially codifying housing discrimination.

Despite the setback and an ensuing conservative backlash with the election of Ronald Reagan to the governorship two years later, the efforts by the L.A. coalition of activists illuminated the baleful consequences of institutional racism, created a paradigm to build a grassroots movement for future campaigns against exclusionary practices and set in motion new court challenges, resulting in the Supreme Court declaring Prop 14 unconstitutional in 1967 and the passage of the Fair Housing Act by the US Congress one year later (12-14, 78-118).

Relocating the Origins of the American Gay Rights Movement

In June 2016, President Barack Obama announced the creation of a Stonewall National Monument in front of the Stonewall Inn in New York City to mark the rebellion by members of the LGBT community who challenged the police during an unwarranted raid, with lesbians and trans women of colour key figures in the resistance. According to textbooks and the U.S. government, the Stonewall Uprising sparked the American LGBT movement and served as a catalyst for LGBT activism worldwide. In Chapter Eleven, ‘Before Stonewall: Gay L.A (1964-1970)’, however, the authors deepen the reigning narrative and historiography.

Nearly two years prior to Stonewall, the LAPD entered the Black Cat Tavern on 31 December 1967 and forcefully arrested more than a dozen patrons for ‘lewd conduct’ (same-sex kissing) to ring-in the New Year. In response, the LGBT community organised the ‘first gay rally against police violence’ and ‘the earliest gay street demonstration’ in the United States (168). In the wake of their groundbreaking and courageous stand for human rights, a flurry of LGBT activism followed over the next three tumultuous years. While the Advocate – a pioneering gay magazine established by Richard Mitch and Bill Rau – anchored the gay rights community through journalism and opinion, a group of LGBT Christians founded the Metropolitan Community Church in L.A. and exponentially increased the size of its congregation by running advertisements in the Advocate. Protests against harassment by the LAPD continued throughout 1968-69, and LGBT activists successfully launched the first officially recognised Gay Pride Parade on 28 June 1970 – one year to the day after the Stonewall Uprising – down the streets of Los Angeles (170-82).

On the Front Lines of Feminism: Los Angeles in the Struggle for Gender Equality

In Chapter 33, ‘The Many Faces of Women’s Liberation (1967-1974)’, Davis and Wiener re-establish Los Angeles as both a focal point and a flashpoint of feminist activism that stood poised to overturn centuries of conventional thought on the role of women in society. Two years after the creation of the L.A. chapter of the National Organization of Women (NOW) in 1967, L.A. NOW appeared outside the fashionable Beverly Hills Polo Lounge to protest its policy of disallowing single women to enter the premises in the absence of a male chaperone. In June 1969, feminists and supporters of L.A. NOW condemned Mother’s Day as a superficial sop to exploited women, called for a rally and demanded ‘a living wage for all women, equal pay for equal work, free child care centers, rehabilitation programs for imprisoned women, ending the special oppression of black and brown women […and] a world without wars’ (584-85).

Radical feminism in Los Angeles only became more brazen – and welcomed. At a feminist bookshop in Venice (a neighbourhood on the Pacific Ocean) in April 1971, Carol Downer, a staunch advocate for women’s reproductive rights and proprietor of a (Women’s) ‘Self-Help Clinic’, publicly examined her vagina and invited the female audience to ‘observe her cervix’ in an effort to teach her subjects how to assess their anatomical health – as women’s bodily concerns remained both somewhat taboo and commanded only a limited number of specialised medical professionals. Her demonstration earned accolades from the event attendees, and news of her bold initiative and support for abortion rights (two years prior to its legalisation) elicited invitations to replicate her talk at venues from coast to coast. One of her clinic coworkers, Lorraine Rothman, also joined the tour and educated women on how to ‘perform very early abortions’ with a simple procedure before Roe vs Wade (585-87). Clearly, the new Baby Boomer generation of women either had begun to question, categorically reject and/or challenge the narrow, stereotypical views of ‘the second sex’ as espoused by traditionalists. When Reverend Billy Graham proclaimed that ‘the word of God teaches that the primary duty of a woman is to be a homemaker’ at the 1971 Rose Parade in Pasadena, California, progressive women and men emphatically disagreed (585).

Past as Present, Past as Future? The Inconclusive Legacy of 1960s Los Angeles

The publication of Set the Night on Fire coincides with a pivotal moment in the life of the ‘City of Angels’. While community activists achieved a number of victories for civil rights, women’s rights, LGBT rights and – fundamentally – human rights during the 1960s and 1970s, African Americans and Mexican Americans remain circumscribed due to a long history of exclusion, currently commanding only ‘one percent of the wealth of whites in Los Angeles’. Not only do African Americans still endure the highest number of LAPD stops and searches without cause, but they also constitute a disproportionate share of both the state prison population and more than 44,000 homeless residents in Los Angeles County.

Beyond a chronicle of a metropolis or an era, Set the Night on Fire thoroughly illustrates the myriad dynamics of inequality, exposes the short- and long-term consequences of discrimination and offers hope in overcoming socio-economic divisions through unyielding activism for equal rights and equal justice – an activism that ought to begin with the question: ‘What happens to a dream deferred?’

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

- Banner Image Credit: (Tony Webster CC BY 2.0).

- Main Text Image Credit: Angela Davis enters Royce Hall, UCLA, for her first philosophy lecture in October 1969 alongside Kendra Alexander (GeorgeLouis CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons).

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2C6XbtO

About the reviewer

Jeff Roquen

Jeff Roquen is an independent scholar based in the United States.