While women have tended to be more supportive of Democrats than Republicans in recent years, the gender gap in support for Donald Trump between men and women is exceptionally large, write Harold Clarke, Marianne Stewart, Paul Whiteley and Guy D. Whitten. They argue that a combination of poor economic factors, women’s party identification, and many women’s personal dislike for Trump are all significant factors in the gender gap in support for the president.

While women have tended to be more supportive of Democrats than Republicans in recent years, the gender gap in support for Donald Trump between men and women is exceptionally large, write Harold Clarke, Marianne Stewart, Paul Whiteley and Guy D. Whitten. They argue that a combination of poor economic factors, women’s party identification, and many women’s personal dislike for Trump are all significant factors in the gender gap in support for the president.

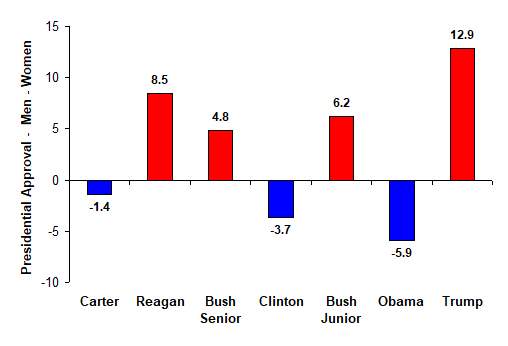

Donald Trump has a three-dimensional gender gap along economic, partisan and personal lines, among American voters that seriously threatens his re-election chances. As monthly public opinion polls summarized in Figure 1 show, where the columns are men’s minus women’s presidential approval ratings (with blue bars for Democratic presidents and red bars for Republicans), Trump’s gender gap is considerably larger than that for any previous president of either party. On average men are almost 13 percent more likely to support Trump than are women. During his term in office, his approval average among men is 48 percent, but among women it is only 35 percent.

Figure 1 – Average Gender Differences in Presidential Approval Since 1978

Gender differences in support for Democratic and Republican presidents are not new. The tendency for women to support Democratic presidents more than men has been prominent feature of American politics for many years. Our statistical analyses show that there are three principal sources of Trump’s gender gap. Two of them are “structural” in the sense that they would affect judgments about any president’s job performance. The third is “personal”—how voters react to a specific President. Regarding the structural factors, evaluations of economic conditions and the percentage of Democratic and Republican Party identifiers always have strong effects on the electoral fortunes of presidential candidates, including Trump. But, there is also Trump’s personal image—many women have a very negative view of him. All three factors have driven down Trump’s approval ratings, with the cumulative impact being especially strong among women.

It’s still “the economy, stupid”

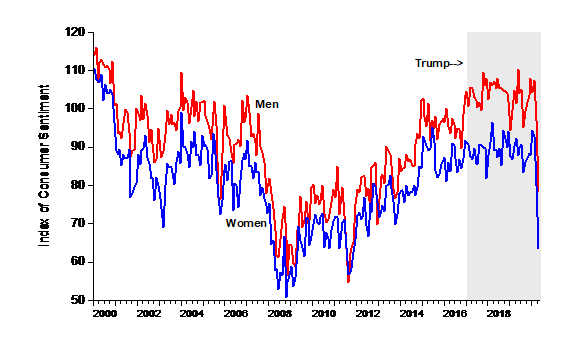

The state of the economy is inevitably politically consequential and often crucial. Economic evaluations powerfully influence voters’ judgments about a president’s job performance and data gathered in the University of Michigan’s monthly Surveys of Consumers reveal consistent gender differences. Since the late 1970s women almost always have been more pessimistic than men about both national economic conditions and their personal financial situation. As Figure 2 shows, during Trump’s term in office differences in consumer confidence between men and women have reached a new high, averaging nearly 15 points. This has occurred despite a strong economy that pushed unemployment among women and ethnic minorities to very low levels before the COVID-19 crisis struck.

Figure 2 – Consumer Confidence by Gender, January 2000-May 2020

Measures taken to combat the pandemic have crashed the US economy and not surprisingly, consumer confidence has fallen sharply in recent months. As shown in Figure 2, the decrease has been especially pronounced among women. Our statistical analyses indicate that consumer confidence has the same impact on presidential approval for both men and women. However, feelings about the economy are considerably more negative among women so the impact on Trump’s performance ratings has been stronger for them. The sharp economic downturn has hurt Trump among both genders, but the effect on women has been especially pronounced.

We the people by Alice Donovan Rouse from Unsplash

The growing partisan divide

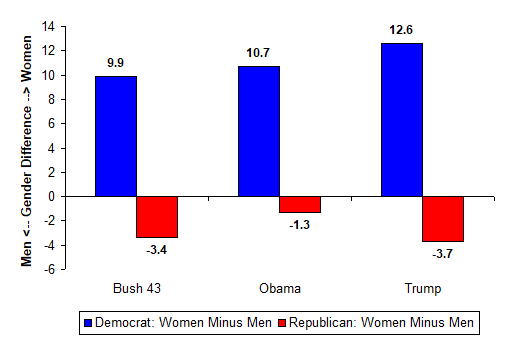

Voters’ psychological identifications with political parties are a second important source of gender differences in Trump’s approval ratings. Research stretching back several decades demonstrates that partisan attachments strongly influence Americans’ political attitudes and behavior, including their judgments about a president’s job performance. Gallup monthly polls conducted over the past two decades show large gender differences in partisanship—women are much more likely to identify themselves as Democrats while men are somewhat more likely to identify themselves as Republicans. Figure 3 indicates that the gender gap in partisanship has reached a new high in the Trump era. Since he took office in January 2017 on average nearly 13 percent more women than men identify themselves as Democrats while about 4 percent more men than women say they are Republicans.

Figure 3 – The Gender Gap in Party Identification Since 2000

These gender differences in partisanship are consequential. Our statistical analyses show that the percentages of voters identifying themselves as Democrats or Republicans at any point in time have large short-term and long-term impacts on trends in presidential approval. With the 2020 election only four months away, the Democrats’ partisan advantage among women has played a big role in driving down Trump’s approval numbers.

With Trump, it’s personal

Differences in presidential performance ratings prompted by gender differences in consumer confidence and partisanship are persistent features of American politics. They influence voters’ judgments about a president regardless of who occupies the White House. However, Trump’s low approval numbers also have a personal component that varies widely by gender. Taking into account the effects of consumer confidence, partisanship and several major international and domestic events, our statistical models show that presidential approval fell abruptly by fully 13 points among women the month after Trump took office. The comparable decrease among men was much smaller and not statistically significant. “Trump being Trump” has affected his job approval ratings among women right from the beginning of his presidency. This was readily apparent in our surveys at the time of the 2018 mid-term elections when Trump’s support was significantly lower among women than men. Structural factors aside, the president’s gender problem clearly has personal dimension—many women simply do not like him.

At the moment, many polls show that Trump is lagging far behind his Democratic challenger, former Vice President Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential race. Throughout his term in office, Trump has relied heavily on a buoyant economy to build public support. Facing largely intractable partisan and personal gender gaps, he has repeatedly claimed that he is responsible for bringing unemployment among historically disadvantaged groups, including women, to historic lows. Reacting to the massively negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, he is banking on a sharp economic rebound to validate this claim and save his presidency. Our models indicate that he very much needs such a sharp “V-shaped” return to prosperity. Without it, Trump’s huge three-dimensional gender gap will likely make him a one-term president.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2D4nwJt

About the authors

Harold Clarke – University of Texas at Dallas

Harold Clarke – University of Texas at Dallas

Harold D. Clarke, Ph.D. Duke University is Ashbel Smith Professor, School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas, and Adjunct Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex.

Marianne Stewart – University of Texas at Dallas

Marianne Stewart – University of Texas at Dallas

Marianne Stewart is Professor of Political Science in the School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas.

Paul Whiteley – University of Essex

Paul Whiteley – University of Essex

Paul Whiteley is a Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex. His research interests are in electoral behaviour, public opinion, political economy and political methodology.

Guy D. Whitten – Texas A & M University

Guy D. Whitten – Texas A & M University

Guy D. Whitten is Cullen-McFadden Professor of Political Science and Cornerstone Fellow in the Department of Political Science at Texas A & M University. His primary research and teaching interests are mass political economy, comparative politics, and political methodology.

This is interesting but it would be much more useful if it mapped the gaps onto states and considered the likely impact on the electoral college. Also, while I am here, although the term ‘gender gap’ has become accepted as a term that describes differences between the sexes, it is still incorrect to refer to ‘two genders’.