Thirty years ago, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed by Congress with the aim of addressing the persistent social and economic marginalization of disabled Americans. But, writes David Pettinicchio, weak enforcement and narrow interpretations of the ADA have since limited its effectiveness. He argues that the ADA was only the beginning: now we must extend its values across all social policy arenas.

Thirty years ago, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed by Congress with the aim of addressing the persistent social and economic marginalization of disabled Americans. But, writes David Pettinicchio, weak enforcement and narrow interpretations of the ADA have since limited its effectiveness. He argues that the ADA was only the beginning: now we must extend its values across all social policy arenas.

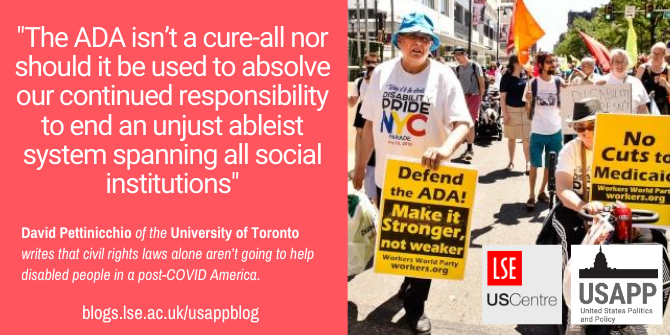

On this thirtieth anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the COVID-19 pandemic reminds us that rights aren’t enough to effectively challenge structural inequality and widespread ableist attitudes and beliefs. Despite the landmark 1990 ADA – the so-called “emancipation proclamation” for people with disabilities – the socioeconomic struggle among disabled Americans is still very real today.

Over the last few months, we’ve reflected on the everyday things we take for granted like where we want to be or who we want to see. That is, the freedom and independence to do what we want, to have control over our everyday life. The social distancing measures some of us have begrudgingly embraced and others, taking them as a challenge to personal freedoms protested against, have us longing for a return to normalcy.

But for many people with disabilities, COVID-19 wasn’t a needed reminder about those taken-for-granted everyday freedoms. Rather quickly, the pandemic revealed deeply entrenched inequalities upheld by discriminatory, ableist beliefs. Things like not getting needed masks, respirators or even medical care simply because disabled lives are seen as less of a priority. Or, a total disregard for the anxiety and panic masks may cause some people with autism or to people who rely on lip reading to effectively communicate.

For people with disabilities at work or in school where life continued remotely, major assumptions were made that employment and academic accommodations mandated by civil rights legislation continued under these new conditions. Yet, many people with disabilities are struggling with unmet needs because appropriate accommodations have not kept up with remote work or study.

These serve as a reminder that people with disabilities remain second class citizens and they will only be further forgotten if something isn’t done throughout and following the pandemic.

Over the last few years, employment rates among disabled people have been at an abysmal 20 percent. During the pandemic, employment rates dropped to a low of around 14 percent. Disabled workers are more often clustered in low-paying jobs in the food and service industry – sectors among the hardest hit by COVID-19. The likelihood that many of these workers with disabilities will resume regular employment is in doubt further exacerbating already large earnings gaps between people with and without disabilities and high disability poverty rates.

“Philly Disability Pride March June 16” by Joe Piette is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0

The ADA: Good intentions, weak enforcement

It was actually nearly 50 years ago that legislators recognized that something had to be done about persistent social and economic marginalization of disabled Americans. Their solution was to extend an existing vocational rehabilitation policy to include civil rights. Members of Congress believed their approach would situate people with disabilities alongside other historically marginalized groups highlighting parallels in their struggles. But this approach was quickly plagued by weak enforcement, legislative compromises and narrow court interpretations all of which also continue to haunt the ADA.

Despite the ADA’s first title which directly speaks to employment discrimination, it’s not a stretch to conclude as many have that the dire socioeconomic situation experienced by people with disabilities today is in part a failure of policy, and indeed, the political process more broadly. But, the fact of the matter is that rights laws alone – at least as we know them – are not enough to deal with the kinds of inequality people with disabilities are experiencing. And, this has been made even more acute by the pandemic. Put differently, rights remain platitudes when there aren’t effective social welfare, health and educational supports to make those rights meaningful.

The need for better home and community care

A particularly good example of this is the continued fight for home or community-based care. The pandemic has raised the stakes in the national crisis around care as nursing homes became COVID-19 hotspots and social distancing measures have made it nearly impossible for care workers to enter people’s homes. The pandemic should be shining a brighter spotlight on the rising number of adults with disabilities under 65 needlessly placed in these facilities – even when the ADA and the Supreme Court in the 1999 Olmstead case made institutionalizing disabled people discriminatory and illegal if they could live in their communities with adequate supports.

But herein lies the problem: adequate supports within the American healthcare system are seriously lacking. Home care unlike nursing home care isn’t an entitlement under Medicaid, currently the largest funder of care for people with disabilities. Home care is among the first targeted for cuts when threats to Medicaid funding are made – despite the right to live free from restrictive and isolating environments.

The ADA should be just the start

While we celebrate the ADA, we should also acknowledge that it wasn’t the end of a process, it was the beginning. The ADA isn’t a cure-all nor should it be used to absolve our continued responsibility to end an unjust ableist system spanning all social institutions. For rights to work, a more systematic integration of their principles and a wide recognition of their inherent value must be extended to all social policy arenas. Without adequate social supports, we cannot expect civil rights alone to address inequality. This is an all too important point given the talk about returning to a post-pandemic normal. To many, returning to normal means returning to confinement, to low-paying jobs or to no job at all. The new normal can certainly mean going back to the status quo or something even worse. But it doesn’t have to. The new normal can be an opportunity to right the wrongs disabled people face. To do that though, we must look beyond the ADA to a larger set of policies that continue to ignore disabled Americans and their rights.

This article is based on the new book Politics of Empowerment.

This article is based on the new book Politics of Empowerment.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/31wqlN8

About the author

David Pettinicchio – University of Toronto

David Pettinicchio – University of Toronto

David Pettinicchio is assistant professor of Sociology and affiliated faculty in the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. His new book, Politics of Empowerment: Disability Rights and the Cycle of American Policy Reform (Stanford University Press, 2019), investigates how and why seemingly entrenched policies like the ADA succumb to retrenchment efforts and the important role of both political elites and everyday citizens in mobilizing against these political threats.