In Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College?, Alexander Keyssar unpacks the history of the Electoral College and explains why it persists despite longstanding criticism of the system and efforts to reform or abolish it. Adeptly written and bringing to light untold stories, this book should be read by anyone interested in the upcoming US presidential election, recommends Kyle Scott.

Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College? Alexander Keyssar. Harvard University Press. 2020.

On 3 November 2020, voters in the US will go to the polls and cast a ballot for either President Donald Trump or his challenger, Joe Biden. The person who gets the most votes may not win the presidency. Four years ago, once all the votes were tallied on election night in 2016, Trump had lost the popular vote to Hillary Clinton but won the electoral vote, thus making him the 45th President of the United States. Writing this review as an American voter, this peculiar mechanism by which we elect our president may once again produce a president who most voters do not want to win.

On 3 November 2020, voters in the US will go to the polls and cast a ballot for either President Donald Trump or his challenger, Joe Biden. The person who gets the most votes may not win the presidency. Four years ago, once all the votes were tallied on election night in 2016, Trump had lost the popular vote to Hillary Clinton but won the electoral vote, thus making him the 45th President of the United States. Writing this review as an American voter, this peculiar mechanism by which we elect our president may once again produce a president who most voters do not want to win.

Alexander Keyssar’s book, Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College?, is perfectly timed with the next presidential election less than four weeks away. Keyssar unpacks the history of the Electoral College and explains why it persists despite its lack of popularity and violation of democratic norms.

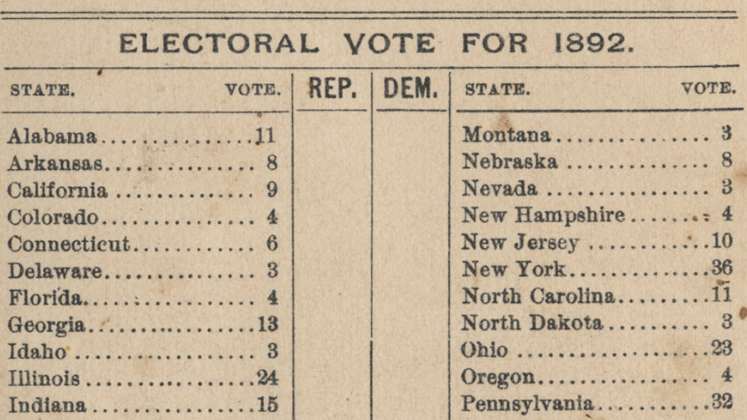

The Electoral College is the body which elects the President of the United States. It forms every four years to elect the president and then disbands. Electors are apportioned to states based upon the state’s representation in Congress. Texas has 38 electors (36 representatives in the House of Representatives plus two Senators) and Montana has three electors (one representative in the House of Representatives plus two Senators). Electors are chosen by each state’s legislature. The process of choosing who gets to be an elector varies per state. When casting a presidential ballot in the US, a voter is effectively casting a ballot for a slate of electors that represent the candidate’s party in the Electoral College. Whichever party wins the popular vote in the state wins all of that state’s electors — electors are not divided up proportionally to the candidates with the exception of Maine and Nebraska.

Keyssar tells a riveting and winding tale about attempts to reform the Electoral College and replace it with either a national popular vote or a distribution of electors in proportion to the state’s popular vote. The author is a captivating storyteller who brings to life events and individuals who might have otherwise been forgotten. For instance, he tells the story of the political odd couple, the Republican Henry Cabot Lodge and the Democrat Ed Lee Gossett, who together introduced a proposal that would effectively get rid of the Electoral College in 1948. Although ultimately unsuccessful, the Lodge-Gossett Resolution is an important story about two political opponents coming together for a common cause.

The book takes the reader through the history of reform efforts from the drafting of the constitution in 1787 until the present day. It does not follow a strict chronological order but is broken down by thematic epochs to help the reader understand the defining debates of various reform efforts. Part One discusses the early debates about the presidential election to show how the Electoral College was not unanimously supported during the constitutional convention nor during the ratification debates of the constitution. The chaos caused by the Electoral College threatened the stability of the nation in these early days which led to the ratification of the 12th Amendment in 1804. Part Two then goes through a set of reforms designed to eliminate the winner-take-all system and distribute electors based upon the proportion of the popular vote, covering the period 1870 to1960.

Part Three covers roughly the same timeframe (1800-1960), but focuses on efforts aimed at scrapping the Electoral College altogether and replacing it with a national popular vote. The concluding chapters in Part Four examine modern-day disruptions caused by the system and recent elections whose outcomes violated the democratic principle of majority rule, including the election of George W. Bush in 2000 and Trump in 2016. These last chapters bring into focus the importance of reform and how unsettling recent elections have been.

Throughout the book, Keyssar draws upon congressional testimony, third party research and news accounts to debunk common objections to electoral college reform. Supporters of the Electoral College argue that its reform would abandon the ideals of the US founders, disadvantage smaller states, create a rural/urban divide in the electorate, disadvantage minorities living in poor urban communities and violate the republican (as opposed to democratic) ideals embodied in the US Constitution. States’ rights and federalism would also be threatened by electoral college reforms. The author provides convincing counterexamples and enough evidence for the reader to conclude that, while reform would be a departure from the norm, it would be neither an unprecedented departure nor a stark break from the past.

Keyssar’s most powerful analysis occurs when he exposes the racial undertones regarding much of the opposition to reform. His confrontation with racism in the US as it relates to electoral reform — a topic that isn’t often viewed through this lens — is one of the strengths that make this book well worth the read. Keyssar provides original insight on how racism can be a motivating factor in preventing reform. After Keyssar pulls together the relevant evidence, he concludes that reform has threatened a political structure that keeps white males in power at the expense of Black people and other historically disadvantaged groups. The argument is most prominent in Chapter Four but it is a thread that runs throughout the book and is an important area of investigation.

One question raised by this narrative, which the author does not discuss, relates to the fact that there have been many successful reforms that were also opposed on racist grounds. Keyssar notes that barriers to representation have been lifted, and representation increased, with the ratification of other constitutional amendments. Seven of the seventeen amendments ratified after the Bill of Rights have increased representation and removed barriers between the populace and elected officials, and five of the seventeen have dealt directly with the office of the president. If we don’t count the 18th and 21st (concerning the prohibition of alcohol and its repeal, respectively), one-third of all amendments ratified after the Bill of Rights have dealt directly with the office of the president and more than a third have increased representation. The reader is left to wonder what is unique about the Electoral College that separates it from amendments like Women’s Suffrage (19th), Direct Election of Senators (17th), Presidential Tenure (22nd) or Abolition of the Poll Tax Qualification in Federal Elections (24th). All these amendments were controversial and had to overcome entrenched interests — including those with racially discriminatory motivations — in order to be ratified. Unfortunately, the author neither undertakes a comparative study nor uncovers unique aspects within the debate over the Electoral College that would set it apart from these other amendments.

Keyssar concedes that there has been a mosaic of issues standing in the way of electoral college reform that do not align along clear sectional, partisan or ideological lines. Lay on top of this a process that is designed to make reform difficult, and it’s unsurprising that the Electoral College has remained unchanged. The author explores a lot of the causes for stasis except two of the most obvious: no one cares enough to make it happen and there is not a compelling enough reason for change. These possible explanations are not addressed by the author.

The Electoral College captures the interest of the US public once every four years at most. And reforming it gets on the agenda even less frequently as reform efforts only follow a perceived crisis. In the intervening years, when its threat to democracy is not immediate, people forget about the Electoral College. Constituent pressure is not sustained through election cycles so officials have no incentive to pursue reform.

For the reader interested in US history, US political developments or elections, this book is well worth the read. Keyssar writes clearly enough for the general reader and brings to light untold stories that add value for the researcher or student of the Electoral College. Keyssar is an adept storyteller who incorporates new and relevant research that will inform an important discussion for years to come. Anyone interested in the upcoming US presidential election should read this book.

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

- Image Credit: Cropped image of Cleveland Portrait Advertising Card, circa 1892. Collection: Collection University Collection of Political Americana. Cornell University Library. Repository:Susan H. Douglas Political Americana Collection, #2214 Rare & Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Cornell University (Cornell University Library, No Known Copyright Restrictions).

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2GRxcsw

About the reviewer

Kyle Scott

Kyle Scott, PhD, has published five books and over a dozen academic articles on American political development, judicial politics and policy diffusion. His work has also appeared in popular outlets like Forbes.com, Christian Science Monitor, Philadelphia Inquirer, Houston Chronicle and Huffington Post among others. He can be reached at kylescott@alumni.rice.edu.