In Violent Utopia: Dispossession and Black Restoration in Tulsa, Jovan Scott Lewis explores the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in the city’s Greenwood neighbourhood (known colloquially as ‘Black Wall Street’) and its legacies today, including contemporary efforts to rebuild Black prosperity. Rooted in ethnographic sensitivity, this is a detailed, expansive and stirring examination of Greenwood’s history and the inexhaustible pursuit of place-based freedom, writes Thomas Cryer.

Violent Utopia: Dispossession and Black Restoration in Tulsa. Jovan Scott Lewis. Duke University Press. 2022.

For a work completed during COVID-19 in the author’s linen closet, Jovan Scott Lewis’s Violent Utopia: Dispossession and Black Restoration in Tulsa provides a particularly arresting analysis of historical contestations over space. Here, space possessed and dispossessed is a launchpad for freedom dreams, a horizon of racial possibility and engraved evidence of centuries of dehumanising Black and Native Americans: all fertile yet destructive imaginaries revealing the interlocking conflicts over space, politics and race in the ‘Sooner State’ of Oklahoma. Lewis, Chair of Geography at the University of California Berkeley, reveals how violence has slowly seeped into Tulsa’s present urban landscape, becoming product, index and self-perpetuating guarantor of anti-Blackness.

For a work completed during COVID-19 in the author’s linen closet, Jovan Scott Lewis’s Violent Utopia: Dispossession and Black Restoration in Tulsa provides a particularly arresting analysis of historical contestations over space. Here, space possessed and dispossessed is a launchpad for freedom dreams, a horizon of racial possibility and engraved evidence of centuries of dehumanising Black and Native Americans: all fertile yet destructive imaginaries revealing the interlocking conflicts over space, politics and race in the ‘Sooner State’ of Oklahoma. Lewis, Chair of Geography at the University of California Berkeley, reveals how violence has slowly seeped into Tulsa’s present urban landscape, becoming product, index and self-perpetuating guarantor of anti-Blackness.

Particularly since the 2021 centenary of 1921’s Tulsa Race Massacre, much of this story may be familiar to readers. Yet Violent Utopia’s first chapter usefully roots Tulsa’s story in longstanding dynamics of racialised contests over land, as first apparent in Tulsa’s beginnings as an 1830s Muscogee settlement following the Muscogee expulsion from Alabama.

First ‘settled’ by white populations as the San Francisco railroad arrived in 1882, Tulsa boomed into the ‘oil capital of the world’ with 1905’s discovery of the Glenn Pool Field, quadrupling its population to 72,000 in the first decade after Oklahoman statehood in 1907 (12). Part of this boom was Black settlement centred in Greenwood, a community of approximately four square miles that reached a population of 9,000 by 1917. Socially and physically segregated yet economically bound to Tulsa, Greenwood was annexed by Tulsa in 1910, precipitating tighter restrictions on Black freedom of movement. In 1921, these racial anxieties exploded in the most catastrophic incident of calculated racial terror in US history.

Lewis offers a detailed and expansive account of these events. Yet he also theoretically reorients his narrative in unison with broader recent literature that understands racial violence not as the episodic or abnormal outpouring of anger, emotion or intolerance, but rather as an everyday structural mechanism foundational to US racial orders.

Lewis thus sets Tulsa, 1921 as one of many referents – Evansville, 1903; Atlanta, 1906; Chicago, 1919 – which each indicate both distinct outbreaks of extralegal violence and the underlying urban environments that were created, conditioned and stabilised by everyday lawful White violence. Tulsa, 1921 was ‘simultaneously destructive as well as constructive’, leading to an ‘arresting containment of Black Life’ that recalibrated and reasserted long-present White control over the city of Tulsa (27). Facing Tulsa’s subsequent ‘spatial-racial fix’, Lewis’s essential task is to explore ‘the juxtaposition of violence and Black freedom and progress in a direct assessment of the paradoxical circumstances of Blackness in the United States’ (15).

Image Credit: ‘Secretary Fudge Visits Tulsa Oklahoma’ by U.S. Dept of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Public Domain

Violent Utopia painstakingly illustrates how ‘long after the riot, that violence would continue to mark the life and experiences and circumstances of Greenwood’s descendants, now located in what was figured as North Tulsa’ (15). Dispossession names those overlapping blows of violence and isolation produced under the guise of integration, the ‘double wake of material privation through urban renewal and the semiotic dispossession represented in the narrative of the massacre’ (5).

Chapters Two and Three, for example, illustrate how the ‘slow massacres’ of municipal disinvestment, blockbusting, over-policing and Tulsa’s general southward development all combined into North Tulsa’s present-day paucity of grocery stores and overall service provision. Such marginalisation indicates the ‘precariousness and vulnerability of intergenerational poverty, a more damning form of violence than any massacre’ (54). Infant mortality and unemployment rates for Black Tulsans remain three times those of White Tulsans, whilst North Tulsa has half of South Tulsa’s median income and is 35 per cent deeply impoverished compared to 13 per cent in South Tulsa (55-56).

These statistical deficits are enlivened as the Tulsans Lewis meets are voiced across entire pages, their registers combining in a ‘Great Gathering’ community session discussing opening a grocery store that speaks to the community’s persistent creativity. Here, Lewis’s analysis owes much to a rich intersection of history, economics and geography. Yet his ethical disposition is acutely ethnographic, ‘anchored by an explicit commitment to the empirics that only considerate and considerable ethnography can command’ (ix).

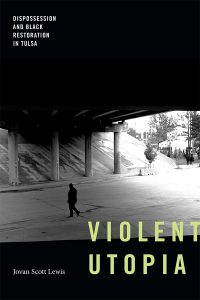

A striking set of black-and-white photographs also evidences how Tulsa’s present landscape archives this violence. The particularly resonant cover photograph shows an anonymous man walking under Interstate 244 where it intersects and domineers over Greenwood Avenue, splitting the community and becoming ‘a damning metaphor for the community’s inability to entirely overcome the forces of its dispossession’ (142). This photograph beckons the reader to explore how history can be mediated through such mundanity; how local indignities are meted out under the shadows of federal provision in a city that, as of 2019, dedicated a third of its budget to policing and only 4 per cent to socioeconomic development (60).

Chapter Four’s thorough yet readable account of reparation campaigns situates Greenwood as a powerful historical ballast for those facing poverty, incapacity and the constant alienation of Black humanity. Greenwood ‘served to articulate and validate the present’s concerns, needs, and hopes’ and remains a ‘geography of memory and aspiration’ (5).

Yet Lewis also underlines how the ‘Black Wall Street’ mythos that disproportionately celebrates Greenwood’s pre-Massacre economic prosperity sits uncomfortably alongside a dependency on external non-profits and churches that pursue community and behavioural ‘improvement’ with Black Wall Street as their resurrectionary goal. Indeed, ‘Black Wall Street’ boosterism ties Tulsa’s remembrance into celebrating a prosperity undergirded by segregation, obscuring the intraracial inequality of what ultimately remained a highly economically-concentrated district prior to the Massacre. Recent ‘Greenwood’-stamped gentrifying developments and the commercial fever surrounding 2021’s centennial left little room for such nuances in their search for an uncomplicated and appropriable form of ‘general Blackness’ (156).

Violent Utopia is also an important landmark in Oklahoman history, its final fifth chapter extending North Tulsa’s ‘repository of meaning’ to ‘the geography of freedom that was Indian Territory’ (175). Moving to displace plantation geography as the fundamental ordering principles of Black spatial imaginaries, Lewis situates Indian Territory as a ‘primary reference for the ethics and identity that form and inspire the North Tulsa Community’ (176).

Lewis remains attentive to the twinned expulsions of Indigenous groups from Indian Territory and the counter-Reconstruction violence that Black ‘Exodusters’ fled to Indian Territory to escape. Yet Indian Territory’s novel and differently racialised territoriality – its capacity to fulfil Reconstruction’s promise of ‘forty acres and a mule’ – grounded an alternative, material conception of a self-determinist Black Utopia. North Tulsa, Lewis suggests, inherits this ethos, articulating a ‘full experience of […] sovereign belonging, which is defined by the terms of inalienability and ownership but effectively by a sense of emplacement’ (196).

Precisely after Presidential recognition and popular depictions including HBO’s Watchmen have afforded Tulsa’s Race Massacre an unprecedented cultural prominence, Violent Utopia is an instructive, theoretically-driven complement to primarily narrative accounts, including Scott Ellsworth’s The Ground Breaking. Violent Utopia’s findings shed a searching light on Oklahoman history but are not limited to or by it. Whilst humble enough to only define itself as a ‘minor contribution’ to the reparations movement, Violent Utopia’s great strength is an analytical dexterity that studiously balances the dialectical dance of anti-Black violence and Black freedom dreams. Its theoretical virtuosity may admittedly restrict its audience, and the current symbolic power of the ‘Black Wall Street’ mythos will undoubtedly prove difficult to displace. Yet Lewis’s theory always remains rooted in ethnographic sensitivity, offering a stirring examination of Tulsa’s less-told story which asserts both historical geography’s analytical potential and its global resonance with the inexhaustible pursuit of place-based freedom.

- This review first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3h5eAaF