In Me, Not You, Alison Phipps builds on Black feminist scholarship to investigate how mainstream feminist movements against sexual violence express a ‘political whiteness’ that can reinforce marginalisation and oppression and limits the capacity to collectively achieve structural change and dismantle violent systems. This short and accessible book challenges us to think deeply about how the politics of woundedness, outrage and carcerality are embedded within the feminist movement and our own organising, writes Lili Schwoerer, and serves as another encouragement to explore and engage with alternative imaginaries.

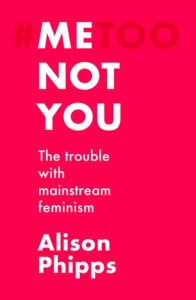

Me, Not You: The Trouble with Mainstream Feminism. Alison Phipps. Manchester University Press. 2020.

Me, Not You, authored by Alison Phipps, Professor of Gender Studies at Sussex University, offers a timely analysis of the connections between mainstream feminism, racism and carceral politics. Drawing on Black feminist scholarship while elaborating on the concept of ‘political whiteness’, Phipps investigates how mainstream feminist movements against sexual violence can reinforce the oppression of women who are not white, middle-class and/or cisgender. Her critique provides essential reading for white women involved in teaching and organising around sexual violence, as well as being of interest to all those seeking to understand and work against gendered and intersecting inequalities.

Me, Not You, authored by Alison Phipps, Professor of Gender Studies at Sussex University, offers a timely analysis of the connections between mainstream feminism, racism and carceral politics. Drawing on Black feminist scholarship while elaborating on the concept of ‘political whiteness’, Phipps investigates how mainstream feminist movements against sexual violence can reinforce the oppression of women who are not white, middle-class and/or cisgender. Her critique provides essential reading for white women involved in teaching and organising around sexual violence, as well as being of interest to all those seeking to understand and work against gendered and intersecting inequalities.

This short, accessibly written book pivots around the #MeToo movement, which, according to Phipps, provided a powerful opportunity to highlight the widespread nature of sexual violence, while also replicating and exposing some of the longstanding violences of mainstream feminism. The feminism that Phipps critiques here is Anglo-American, public feminism: the kind of feminism which is most hegemonic, and most visible, in corporations, NGOS and institutions, including universities. The book’s six short chapters draw together historical and conceptual analysis with empirical observations on the ways in which the tendencies to co-opt the work of women of colour and to centre white woundedness shape these kinds of feminist organising, and the political landscape more generally.

Phipps acknowledges that much of her analysis is not new to those immersed in Black feminist thought and is thus primarily directed at white women like her – and me – that are ‘interested in doing their feminism differently’ (11). She discusses the complexities that arise from her own positioning in relation to the topic she critiques, and the fact that critiquing whiteness from within can both re-centre it and reproduce some of its most vicious tendencies. Rather than seeking to solve these complicities, she leaves them open to critique, noting the incompleteness and collaborative nature of all knowledge production.

Chapter One, ‘Gender in a Right-Moving World’, situates sexual violence and gender inequality in the socio-economic formations specific to contemporary neoliberalism: the crisis of social reproduction and resulting precarity, the defunding of services providing safety for survivors and the global move towards the political right. Drawing on scholars such as Silvia Federici and Maria Lugones, Phipps links these newer formations to the historical development of racial capitalism through the intertwined structures of (settler-)colonialism and heteropatriarchy, connecting them to the centrality of the nuclear family in neoliberal capitalist, white-supremacist society. These formations, she argues, are central to contemporary right-wing ideology, which controls the bodies of women through restrictions on reproduction while simultaneously weaponising white women’s safety for racist and xenophobic means.

In the context of austerity-induced politics of scarcity, the control of women’s bodies intersects with increased fear and scapegoating of those who are constructed, often in contradictory ways, as ‘Other’. Phipps convincingly argues that these politics connect the far right, including the global anti-feminist backlash, with some forms of mainstream feminism, in particular those which seek to demarcate the boundaries of ‘womanhood’, excluding transgender women from its community. Later in the book in Chapter Five, she demonstrates that these connections are far from symbolic; they manifest in material links and coalition-building between the far right and anti-trans feminist groups (see also Lola Olufemi, 2020).

Phipps most skilfully connects histories of the feminist movement to its contemporary shortcomings in Chapter Two, ‘Me, Not You’. She retraces Black feminist critiques of the women’s movement, demonstrating how the subject of today’s mainstream feminism has arisen from white, Eurocentric, bourgeois and essentialist constructions of ‘respectable’ womanhood, which have always stood in opposition to women of colour and working-class women. She argues that these constructions, which leave no space for theorising the intersections between gender, race and class, have led to a mainstream feminist understanding of the essentialised white woman as a uniquely and maximally oppressed subject, while violence becomes located in the (again essentialised) male body. The white (feminist) self is then fundamentally a wounded self and preoccupied with threat: ‘’the cultural power of mainstream feminism is linked to the cultural power of white tears’ (72).

The core concept of ‘political whiteness’, discussed in detail in Chapter Four, allows for an elaboration of this point. Political whiteness ‘describes a set of values, orientations and behaviours that […] include narcissism, alertness to threat and an accompanying will to power’, and which is produced by the interaction between supremacy and victimhood (6). The concept thus opens up an analysis that recognises that the positions of ‘victim’ and ‘perpetrator’ are not mutually exclusive, and which draws parallels between mainstream feminism and some of its most vocal, right-wing critics.

The concept of political whiteness also allows Phipps to explore the affinity between mainstream feminism and the carceral state. Drawing on Elizabeth Bernstein’s notion of carceral feminism, as well as on Black feminist abolitionists such as Mariame Kaba, Phipps explores how the most public voices in the #MeToo movement have been focused on punishing individual ‘bad men’, despite the explicitly structural focus of the movement’s original founder, Black feminist Tarana Burke. This, she argues, risks not only leaving violent structures intact, but also invests in a system which has violence against people of colour at its core.

Phipps’s theorisation here successfully balances the individual and the structural: while she underlines that political whiteness is not merely a personal attribute of white people, she reflexively explores how white women in particular have internalised and reproduced these structures. This distinguishes her work from most other, earlier theorisations of ‘neoliberal’ or ‘corporate’ feminism: the focus on material histories of race and colonialism complicates narratives of contemporary feminism having merely ‘sold out’ or ‘lost its way’.

Phipps’s contribution to contemporary feminist scholarship is perhaps most pronounced in Chapter Four, ‘The Outrage Economy’, which theorises the relationship between narratives of survivorhood and trauma and contemporary political economy. Phipps, drawing on Jodi Dean’s concept of ‘communicative capitalism’, amongst others, explores how media outrage has amplified the carceral tendencies of the dominant voices in the #MeToo movement, and of mainstream feminist activism more generally.

Phipps writes emphatically about the needs of survivors to express their trauma and for it to be taken seriously, while also exploring how the public value of ‘trauma capital’ is structured by gender, race and class; trans women, women of colour and sex worker’s experiences of violence are less likely to be taken seriously than those of white, middle-class, cisgender women. In an ‘outrage economy’ structured by political whiteness, trauma can become currency in campaigns against trans women’s and sex workers’ rights. Middle-class cisgender women are most likely to be heard and amplified, and are able to navigate this economy best. Importantly, Phipps also discusses how outrage about sexual violence, in combination with punitive responses to it, can actually distract from understanding, and organising against, structural violence.

As such, this short and accessible book challenges us to think deeply about how the politics of woundedness, outrage and carcerality are embedded within the feminist movement and our own organising. In a moment in which calls to ‘take down violent men’ remain frequently voiced in the public sphere, thinking hard about the violence that could be enacted precisely through such responses is paramount. As abolitionist thinkers such as Kaba argue, the alternatives are not easy, one-size-fits-all solutions, but legacies of organising can serve as guidance, and ‘non-reformist reforms’ can bring us closer to a world free from violence. Phipps’s book serves as yet another encouragement to explore and engage with these alternative imaginaries deeply.

- This article originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

- Image Credit: Sign reading ‘I’m With Her’ from Women’s March Los Angeles, 2017 (Larissa Puro/USC Institute for Global Health CC BY 2.0).

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2Ulrnax

About the reviewer

Lili Schwoerer –LSE

Lili Schwoerer is a PhD candidate in Sociology at the LSE. Her thesis explores how gender and feminist knowledge production in English universities is shaped and reshaped in the context of Higher Education marketisation and internationalisation. You can follow her on twitter @lili__lilian

1 Comments