Spending by political campaigns on contests which range from party nominations to House, Senate and presidential elections have increased dramatically in recent years, with the 2020 US elections being the most expensive on record. Recent trends shown that the victor generally outspends their opponent, but William CR Horncastle argues that greater spending alone cannot guarantee success.

Spending by political campaigns on contests which range from party nominations to House, Senate and presidential elections have increased dramatically in recent years, with the 2020 US elections being the most expensive on record. Recent trends shown that the victor generally outspends their opponent, but William CR Horncastle argues that greater spending alone cannot guarantee success.

The 2020 US Election has been the most expensive electoral contest in history. With forecasts suggesting that total costs will reach $14 billion, spending in the 2020 cycle equates to more than double that of 2016. Fundraising has become an essential precursor to electoral participation, with the average costs of winning a 2016 House or Senate race calculated at $1.3 million and $10.4 million, respectively. Increased election costs, which are now comparable to the annual GDP of some small nations, have not only been shaped by a significant growth in candidate spending, but a continued rise in campaigning by ‘outside’ groups since Citizens United v FEC. With campaign costs continuing to rise, does spending correlate with success?

Self-Funding and Success

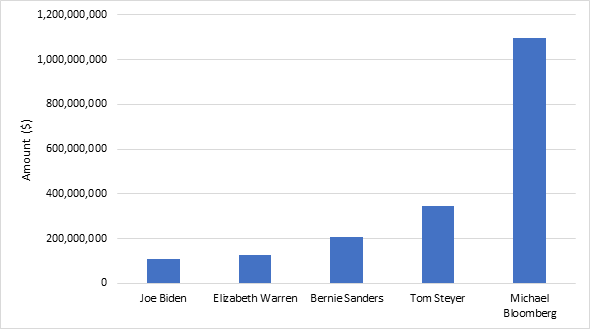

With the total cost of the 2020 Elections exceeding the 2016 spending record, the cycle contained the most expensive individual candidate campaign ever, as shown in Figure 1. Running in the Democratic primaries, former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg self-funded his campaign with more than $1 billion. Discussing his decision in a CBS interview, Bloomberg claimed that self-funding was the best option, stating that “nobody gives you money if they don’t expect something”. Although Bloomberg had a clear funding advantage relative to all other candidates, he earned the support of just 59 delegates and pulled out of the race in March 2020. The Democratic primaries presented an additional self-funded run from billionaire hedge fund manager Tom Steyer, whose $340 million campaign attracted less than 1 percent of the popular vote, and zero delegates. These self-funded campaigners were unable to gain the candidacy ahead of Joe Biden who, spending just $165 million, won the contest as the fifth highest spender. These figures suggest that spending does not always lead to success.

Figure 1 – 2020 election Democratic Primary Campaign Spending

Source: Opensecrets

Although traditional candidates, funded by contributions from outside sources, have an economic incentive to act in the interests of their donors, self-funded candidates do not hold this responsibility. Indeed, while self-funded candidates may enjoy greater financial power, they often lack in other important areas that would attract a supporter base. While money plays an essential role in gaining exposure, financial contributions from outside sources can be an additional avenue for public support, explaining why self-funded candidates like Michael Bloomberg in the 2020 Democratic primary, often fall short in electoral contests.

Spending and Presidential Elections

Presidential races are generally won by the highest spender, but the lack of success in fully self-funded candidates suggest that money alone cannot win an election. In the 2020 Election, for instance, spending by Joe Biden’s campaign committee exceeded that of Donald Trump by roughly $200 million. This is an extension of recent trends; in three of the four previous elections (2004, 2008, 2012), the eventual victor outspent their challenger.

Since the turn of the century, the outlier to this pattern was the 2016 election, wherein Hillary Clinton spent roughly $450 million, relative to Trump’s $239 million outlay. Trump ran an unconventional campaign ‘tapping into a populist vein’ that no other candidate had previously been able to which, when combined with his celebrity status, earned significant media attention. In the 2016 election alone, Trump’s ‘free’ media exposure was valued at an estimated $2 billion, compared to the comparable figure of almost $750 million for Clinton.

Although general trends show that the highest spending candidate often wins, Trump’s intangible characteristics and ability to gain support through unconventional means heightened his organic media presence, providing exposure that Clinton lacked. In 2020, however, as an incumbent who lacked his 2016 ‘upstart’ factor, Trump was unable to replicate these successes, becoming the first single-term President since Republican George H W Bush, who lost the 1992 election.

“Photo by Brendan Hoffman” by Public Citizen is licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0

Ineffective Democrat Spending in House Races

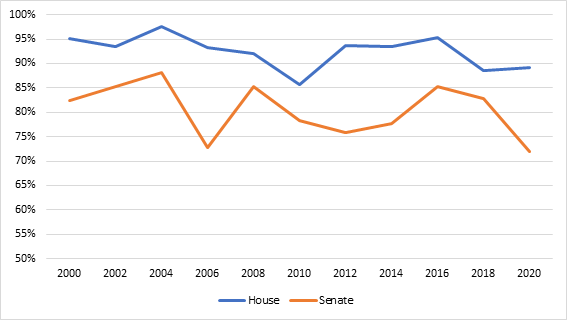

Following patterns in Presidential races, House elections are generally won by the better funded candidate. Since the turn of the century, the proportion of elected representatives that outspent their opposition has ranged from 88 percent to 97 percent. In the 2020 elections, as Figure 2 shows, this remained stable, with almost 90 percent of winning candidates committing the highest spending in their respective races.

Figure 2 – Percentage of House and Senate Races Won by Highest Spender, 2000-2020

House elections in 2020 produced losses for the Democrats, with eight districts being ceded to Republican challengers at the time of writing. These defeats were generally freshman members, with most representing districts flipped from the Republicans in the 2018 midterms. Interestingly, in all eight districts regained by Republicans, Democrat incumbents were the highest spenders. Candidates in Florida’s 27th District, Minnesota’s 7th District, and California’s 48th District were separated by minor differences in spending, with amounts ranging from $100,000 to $300,000. In the five remaining Republican gains, differences in spending were more significant. In Florida’s 26th District, incumbent Democrat Debbie Mucarsel-Powell lost her seat to Republican challenger Carlos Gimenez, despite outspending her challenger by $3.9 million. Similarly, in New Mexico’s 2nd District, Republican challenger Yvette Herrell was elected, despite spending $4.1 million less than the incumbent Democrat Xochitl Torres Small. Although Republicans made gains, some high spenders within the party were unsuccessful in their races. Republican Lacy Johnson spent almost $9.8 million in Minnesota’s 5th District, for instance, he was unable to unseat incumbent Democrat Ilhan Omar.

A ‘Blue Wave’ of Senate Spending

Fundraising for Senate races reached record levels in 2020, with Democrats and Republicans raising $809 million and $494 million, respectively. Although the largest spenders in Senate elections, which incur considerably more expense than House contests, generally defeated their opponents, almost 30 percent of 2020 races resulted in victory for the lesser spending candidate. This figure represents the largest proportion of such instances since the 2006 mid-terms, where Democrats flipped the Senate after alleging a ‘culture of corruption’ within the Republican Party.

Democrats embarked on significant spending in several Republican strongholds, but were largely unsuccessful. South Carolina produced the most expensive Senate campaign in history, with incumbent Republican Lindsey Graham retaining his seat for a fourth term, despite challenger Jamie Harrison embarking on a campaign exceeding $100 million. Moreover, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell won a seventh term as Senator for Kentucky, despite being outspent by roughly $30 million. In Kansas, following Republican Senator Pat Roberts decision to not run in the 2020 election, Republican candidate Roger Marshall successfully defeated Democrat Barbara Bollier, despite being outspent by a ratio of almost 4:1. The general ineffectiveness of challenger spending was exhibited in the ten most expensive Senate races in 2020, where the highest spending candidate won in just four instances. In the same selection of races, the incumbent won in seven cases, largely influenced by surging Democrat campaigning in entrenched Republican areas.

Money cannot purchase elections

With the cost of campaigning continuing to rise, money is still a key factor in determining who wins an election. And while most Presidential and Congressional races are won by the highest spender, there are many other factors beyond money which can influence the eventual outcome. In the 2020 Democratic primaries, for example, self-funded candidates like Michael Bloomberg were unable to gain sufficient support. In 2016, Trump gained enough exposure to win the Presidency, despite being outspent by almost $200 million. While Biden’s spending was sufficient to win the White House in 2020, Democrat spending in Congressional elections appears to have been generally ineffective; Democratic incumbents in House races were unseated by lesser spending Republican challengers, while high spending Democrat challengers in Senate races were unable to win in key Republican States. As the 2020 election has shown, while spending is an essential factor in winning a campaign, elections cannot be bought by the highest bidder, as many fear.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3fEW3NN

About the author

William Horncastle – University of Birmingham

William Horncastle – University of Birmingham

William Horncastle is a third-year PhD candidate at the University of Birmingham’s Department of Political Science and International Studies. His current research focusses on comparative analysis of political finance systems around the world. Previously, he has undertaken research into the causes of, and regulatory responses to, the Financial Crisis of 2008. (Twitter: @willhorncastle)