The 2020 US Presidential election campaigns have raised questions about the media and its credibility among US citizens. While many view the media as an important part of democracy, there is also an awareness of its role in furthering political divisions. Brian Calfano, Richard Harknett, Gregory Winger and Jelena Vicic examine the crucial relationship between the government and the media, and its broader implications for restoring faith in election coverage.

The 2020 US Presidential election campaigns have raised questions about the media and its credibility among US citizens. While many view the media as an important part of democracy, there is also an awareness of its role in furthering political divisions. Brian Calfano, Richard Harknett, Gregory Winger and Jelena Vicic examine the crucial relationship between the government and the media, and its broader implications for restoring faith in election coverage.

The contested outcome of the 2020 presidential election highlights both the public’s widespread dislike for the media and, simultaneously, the essential role that media plays in the political process. Rather than being a cure for polarization, the fractured media environment and perceptions of media bias may contribute to America’s persistent political divisions. A Gallup Poll prior to the election found that 60 percent of Americans distrust the media, with 89 percent of Republicans expressing little or no trust.

Yet, a duality exists. A joint Gallup and Knight Foundation report from August 2020 found that 84 percent of Americans view the media as important to democracy. Moreover, the public values the media for providing information and holding those who have power accountable. This means that, in the course of doing its due diligence in reporting stories that raise partisan ire, the media may gain audience credibility for reporting on items like government response to election fraud claims—even those advanced by certain political leaders (as seen in the November election’s immediate aftermath). But, also as seen in the unfolding political drama with President Trump and election returns, stories that counter fraud claims may exacerbate public dissatisfaction with media (especially among partisans with a personal stake in the fraud narrative).

This raises an important question related to an election marred by simultaneous claims of fraud and security: does the media improve its public image when it reports on government responses that the fraud is non-existent?

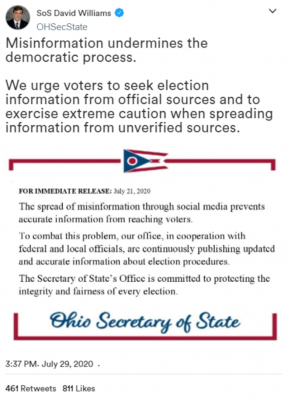

To assess, we incorporated a battery of media perceptions as part of a larger survey experiment testing the effectiveness of election officials in combating disinformation. The experiment used Lucid’s national opt-in panel from October 3-5, 2020, and randomly assigned 8,809 American adults to groups with one of seven conditions. The first group is a pure control consisting of entertainment and non-political stories to provide a baseline. The second group included news stories and tweets concerning a prominent and recurring theory that absentee ballots can be submitted for dead people. The third and fourth groups presented the same “voting dead” information, but with counter-messaging provided by a Secretary of State (SoS) office and modeled on existing communications from current election officials using reassurance or transparency messaging telling the public these fraud allegations are false.

Groups 5-7 were presented with identical materials as 2-4, but replaced the generic office with a named SoS. Using a named SoS reflects common practice in most US States and added a series of stories about leaked emails from the SoS. Figure 1 includes an example of the named SoS (fictitious) from the sixth group.

Figure 1

Random assignment was not correlated with subject demographic characteristics, including partisanship, and response to open-ended questions show that subjects recalled the general subject matter addressed in each assigned treatment.

Photo by Roman Kraft on Unsplash

Because our experiment involved the presentation of media information about election malfeasance and public-facing statements by a Secretary of State to correct misperceptions, we used a battery of Pew-inspired questions asking subjects their level of agreement (on a scale of 0-10 where 10 was ‘agree strongly’) with the statements that: individuals reporting news stories were helpful to others or could be trusted; and that experts quotes in news stories were helpful to others or could be trusted. We used these answers together with a measure of individuals’ ideology to create a “Media Trust” index.

As Figure 2 shows, media trust is reduced significantly when there is no government represented in the content shown to the groups. This is seen clearly in the “No SoS Office Present” treatment reducing the Media Trust index by .4 (almost half a point lower on the 11 point scale versus the control group). That the remaining treatments do not significantly increase the index score might lead some to suggest that the presence of official government statements to quell public concern about election integrity does not really help public media perceptions. That is one interpretation.

Figure 2 – Media Trust Scores

Note: Treatment and Covariate model with Robust SEs

But we think the broader implication is that, while journalists and the experts quoted in stories don’t necessarily make people feel like they can trust the media, our results underscore that the public does notice a critical missing piece of the puzzle in media coverage— the government’s response.

When government’s role and reactions are not included in stories about election processes, media trust suffers. Whether public trust in media can be significantly increased is another matter, but people’s feelings of trust are not made worse by involving government and expert voices in addressing people’s concerns about elections issues).

The implications, therefore, are for media to ensure that they cover what the government’s officials’ claims about elections are, even, perhaps if they run counter to statements from other political leaders (and increase partisan backlash in the process). The outcome for the press may not be increased public trust, but the alternative is clearly worse.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3ojDou4

About the authors

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian R. Calfano – University of Cincinnati

Brian Calfano is an Associate Professor of Political Science and Journalism at the University of Cincinnati. He has 50 peer-reviewed journal articles to his credit, and is the co-author of God Talk: Experimenting with the Religious Causes of Public Opinion (Temple University Press, 2013), A Matter of Discretion: The Political Behavior of Catholic Priests in the U.S. and Ireland (Rowman and Littlefield, 2017), and Human Relations Commissions: Relieving Racial Tensions in the American City (2020 Columbia University Press).

Richard Harknett – University of Cincinnati

Richard Harknett – University of Cincinnati

Dr. Richard J. Harknett is Professor of International Relations and Head of the Department of Political Science at the University of Cincinnati. He is the author of over forty publications in the area of international relations theory and international security studies, and is the Chair of the Center for Cyber Strategy and Policy at the University of Cincinnati and Co-Chair of the Ohio Cyber Range Institute.

Gregory Winger – University of Cincinnati

Gregory Winger – University of Cincinnati

Dr. Gregory H. Winger is an Assistant Professor in the Political Science Department at the University of Cincinnati. He specializes in cyber security international security, and U.S. foreign policy. His research examines trust-building processes and in particular how collaborative activities, like defense diplomacy, have been used to facility cooperation on emerging security issues.

Jelena Vicic – University of Cincinnati

Jelena Vicic – University of Cincinnati

Jelena Vicic is a PhD candidate at the University of Cincinnati and an Ohio Cyber Range Institute Pre-doctoral Fellow.