Following the 2020 election, there has been some evidence that Donald Trump performed better than polls had predicted among African-American and Latinx voters. Dan Cassino argues that gender identity – not race – may be a better indication of support for Trump. He writes that recent polls have shown that men who identify more closely traditionally masculine gender identity were more likely to vote for Donald Trump. That African-American men were more likely to assert this type of traditional gender identity may go some way towards explaining how they voted.

Following the 2020 election, there has been some evidence that Donald Trump performed better than polls had predicted among African-American and Latinx voters. Dan Cassino argues that gender identity – not race – may be a better indication of support for Trump. He writes that recent polls have shown that men who identify more closely traditionally masculine gender identity were more likely to vote for Donald Trump. That African-American men were more likely to assert this type of traditional gender identity may go some way towards explaining how they voted.

- Following the 2020 US General Election our mini-series, ‘What Happened?’, explores aspects of elections at the presidential, Senate, House of Representative and state levels, and also reflects on what the election results will mean for US politics moving forward. If you are interested in contributing, please contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (p.finn@kingston.ac.uk).

While Democrat Joe Biden won both the popular and the Electoral College vote in the 2020 US Presidential Election by a fairly wide margin, he dramatically underperformed his pre-election polling. Polls had pointed to a lead of 7 to 9 points for Biden; he wound up winning by just four, in an election where downticket Democrats also did worse than had been expected. A common explanation for this Democratic underperformance has been President Trump’s unexpected gains among African-American and Latinx voters – but it seems likely that Trump’s gains with these groups have less to do with race or ethnicity than they do with gender.

The disruptive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic mean that traditional exit polling wasn’t possible this year, and the results of the survey based replacements have been called into question. This means that we don’t yet have great direct estimates of voter breakdowns by race and ethnicity, but the circumstantial evidence for increased Trump support among African-American and Latinx voters is compelling. For instance, Trump did unexpectedly well in both states and counties with large Latinx populations, especially in southern Florida. Interestingly, there also seems to have been a significant gap between the those African-American and Latinx voters who lived in cities, and those who lived in rural areas, with Trump doing much better among less urban African-Americans and Latinx voters.

Gender identity and political views

To many observers, the idea that Trump improved on his numbers among groups that, according to reports, he disrespected frequently during his time in office is baffling. But it makes more sense if we approach the question in terms of gender identity. Gender is often thought of as being synonymous with sex, but gender has more to do with how an individual sees themselves in relation to societal notions of masculinity and femininity. While most men say that they have masculine gender identities to some extent or another, some are feminine, just as most women claim feminine gender identities, but many say that they’re more masculine.

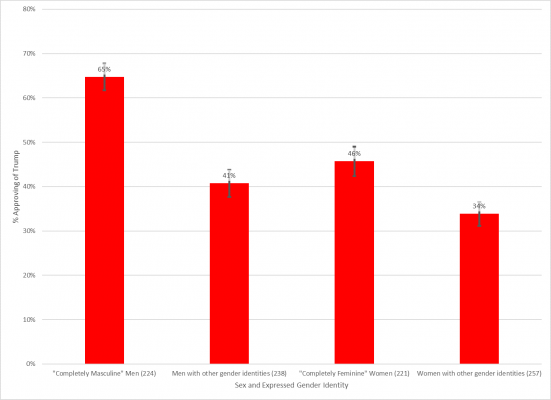

While scholars have long conceptualized gender and sex as being different, it’s only recently that survey researchers have begun actually measuring them independently, allowing us to understand the impact that gender, rather than sex, has on political views, and that difference is enormous. Even controlling for factors like sex, partisanship and education, individuals with what might be thought of as having ‘traditional’ gender identities (completely masculine for men, and completely feminine for women) have much more conservative political views than everyone else, with “completely masculine” men being the biggest outlier. On the whole, for instance, men have higher approval of President Trump than women; but in the results of an FDU Poll from earlier this year, shown in Figure 1, we can see that it’s men who identify with a ‘completely’ masculine gender identity who have high approval of Trump (65 percent); other men are statistically indistinguishable from women.

Figure 1 – Expressed Gender Identity and Support for Donald Trump

So, what does this have to do with increased support for Trump among African-American and Latinx voters? In the same survey, 63 percent of African-American men and 55 percent of Latino men asserted a completely traditional gender identity, compared with 48 percent of white men. While the difference between “completely feminine” women and other women was smaller, it’s still substantial; only 42 percent of white women said that they were “completely feminine” compared with 54 of African-American women and 58 percent of Latinas.

These traditional gender identities are related to other factors that have been shown to be important to political views, like church attendance, educational levels, and living in a rural, versus and urban setting. They’re also related to lower levels of trust in the media and government. Together, these results help to explain Trump’s increased support among some groups, as well as why polling may have missed it.

Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash

While it may be difficult to understand support for Trump among African-American and Latinx voters, a focus on asserting a traditional masculine identity has been one of the most consistent elements of his political rhetoric. As such, Trumps seems to be appealing to individuals with ‘traditional’ gender identities, and his focus on these traits may make them more important to the decision making process of voters than other aspects, like race and ethnicity, which may have been more heavily weighted in the past.

Why the polls may have missed these pro-Trump voters

Why would these shifts in support be missed in polls? First off, polls have a harder time reaching African-American and Latinx respondents already, and resort to weighting strategies to artificially increase their numbers in polls. This means that polls assume that the respondents from these groups that they do reach are representative of the rest of the group; if that assumption fails, the figures will be off. Second, many of the factors associated with a ‘traditional’ gender identity, like low educational levels and church attendance are often associated with a lower propensity to participate in surveys anyway. Put these two factors together, and it means that the people most likely to have shifted towards Trump are the least likely to have taken part in a survey.

The urban-rural divide is also suggestive. Among all Americans, not just members of ethnic and racial minority groups, rural voters are more likely to assert ‘traditional’ gender identities. So, if gender were leading to higher levels of support for Trump, we’d be most likely to see that support be underestimated most in rural areas: exactly what we’re seeing from voter returns.

There are several lessons we can take away from this apparent polling miss. The first is that gender matters. No one thinks that men being more Republican and women more Democratic is driven by biology: any observed sex difference is really a gender difference that we’re not measuring. And when we do measure gender, we find that it’s not as simple as a sex dichotomy might make it seem. The second is that while race and ethnicity have been dominant factors in American political life for decades, there is not guarantee that they will remain so. Social identity theory tells us that individuals have many identities, and the one that’s dominant depends on the situation. As such, we can’t just assume that the same factors will always be the most important, and Democratic candidates can’t assume that race and ethnicity will always trump other considerations.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Notes: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2W2RAv4

About the author

Dan Cassino – Fairleigh Dickinson University

Dan Cassino – Fairleigh Dickinson University

Dan Cassino is a professor of Government and Politics at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Madison, New Jersey, who studies political psychology and polling.