Much of the response to COVID-19 in America in the past year has been led by state governments. In California, Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom is now facing an effort to remove him from office fueled by perceptions that his administration has mishandled its pandemic response. Jeff Cummins writes that while poor crisis management also drove a successful 2003 recall effort which saw Arnold Schwarzenegger replace Democrat Gray Davis, Newsom’s greater popularity and the nearness of the next gubernatorial election are important factors in the current Governor’s favor.

Much of the response to COVID-19 in America in the past year has been led by state governments. In California, Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom is now facing an effort to remove him from office fueled by perceptions that his administration has mishandled its pandemic response. Jeff Cummins writes that while poor crisis management also drove a successful 2003 recall effort which saw Arnold Schwarzenegger replace Democrat Gray Davis, Newsom’s greater popularity and the nearness of the next gubernatorial election are important factors in the current Governor’s favor.

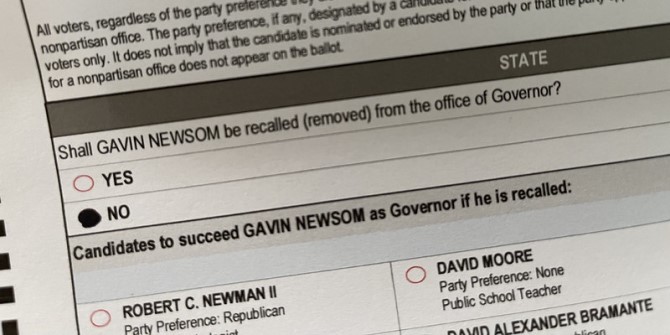

California is on the verge of facing its second recall election of a governor in its 170-year history as a state. The recall allows voters to remove elected officials in between regularly scheduled elections. Unlike impeachment, where elected officials decide whether to remove an appointed or an elected official, in a recall, voters decide two questions: (1) whether to retain the incumbent; and (2) who will replace the incumbent if removed. Currently, a campaign in California seeking to gather voter signatures to trigger a recall election later this year is at or above the signature threshold required to qualify the petition for the ballot. If recall proponents submit about 1.5 million valid signatures, then incumbent Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom would become the second governor in California in the last 20 years, and just the fourth in US history, to confront a recall.

Here We Go Again

California is no stranger to recall elections. It frequently considers recalls of local government officials or school district board members and has seen the highest number of recalled state legislators (9) of any US state. Despite numerous attempts to recall California governors since the tool was adopted into law in 1911, the only successful petition was for the recall of Democratic Governor Gray Davis in 2003. That recall election gained national and international attention when action movie star Arnold Schwarzenegger entered the race and eventually won when Davis was ousted from office.

There are striking parallels between the Davis recall and the current campaign playing out. Crisis management was the driving factor behind the Davis recall as it is for the current campaign to remove Newsom. At the end of the dot.com boom in 2001, California’s finances went into a deep hole that led to a $30 billion state budget deficit. On top of that, an energy crisis resulted in rolling blackouts throughout the state. Governor Davis was accused of mishandling both crises.

Although the nature of the current crisis facing Governor Newsom is different, his mishandling of the COVID-19 response has given the recall effort a strong boost. Inconsistent lockdown restrictions on businesses in different industries have rankled both Democrats and Republicans alike. It also did not help his case when Newsom and his wife attended a swanky lunch celebration for a lobbyist friend after calling for state residents to avoid public gatherings.

The other similarity between the 2003 recall and current campaign is the indispensable role of money and partisanship. In 2003, Governor Davis and his aides did not take the recall seriously until an infusion of money came into the campaign from car alarm magnate and Republican Congressmember Darrell Issa. His $1.7 million contribution gave paid signature gatherers enough resources to meet the voter signature threshold.

Likewise, despite contributions from some Democratic-leaning donors, most of the funding and support for the Newsom recall has come from Republicans, including former presidential candidates Newt Gingrich and Mike Huckabee. Potential Republican candidates to replace Newsom have already declared their intent to run. John Cox, a San Diego businessman who Newsom soundly defeated in the 2018 governor’s race, is one of those, along with former San Diego mayor Kevin Faulconer.

Differences from the 2003 gubernatorial recall

Although there are several similarities to the 2003 recall, the political environment is quite different from the early 2000s. Recall proponents appear to be on a trajectory to surpass the required number of verified signatures, but only because a state judge extended the deadline for gathering signatures by five months due to the logistical challenges of acquiring signatures during the pandemic. Assuming proponents qualify the recall for the ballot, the recall election may not occur until December, which would be less than one year before the next regularly scheduled gubernatorial election in November 2022.

In the Davis recall, the election occurred less than one year (in October) after Davis had been closely reelected the previous November. Voters could sour on the prospect of removing Newsom from office when he will be up for reelection in the next year, perhaps especially when they learn that the election could cost up to $100 million. Voters may decide that it is not worthwhile to remove Newsom so close to an election where he could be removed anyway.

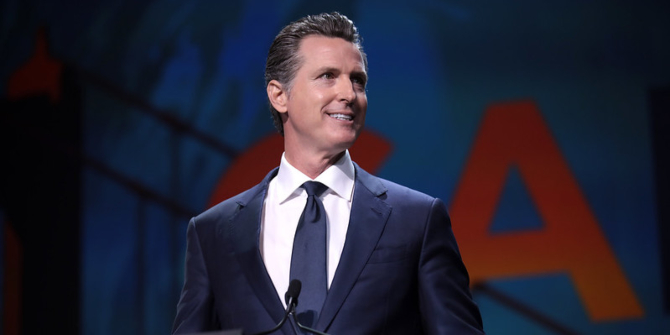

“Gavin Newsom” by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

While Newsom’s standing with the public has dropped with his mishandling of the pandemic response and potentially massive fraud with the state’s unemployment benefits program, his public approval still has not approached the depths that Gray Davis sunk to in 2003. After an initial bump in Newsom’s approval rating at the beginning of the pandemic, recent polls have his approval around 46 percent. Approval ratings for then-Governor Davis were around 25 percent just before his October recall election. Moreover, in the Davis recall, a majority of respondents indicated they were in favor of removal and 55 percent of voters ultimately voted to recall him. For Newsom, only 36 percent of respondents indicated support for removing him in a recent poll, with nearly 20 percent undecided. Unlike the 2002 gubernatorial election, when Gray Davis squeaked by conservative Bill Simon by 5 points, Newsom trounced Cox in 2018 by a nearly 25-point margin.

The Democratic Strategy

A big question looming over Democrats in the state is whether to sponsor an alternative Democratic candidate to Newsom in case voters support the recall. In 2003, the Democratic strategy was to discourage any prominent Democrats from placing their names on the ballot as a replacement for Davis in the hopes that voters would retain Davis as the lone Democrat. This strategy was upended when Lieutenant Governor Cruz Bustamante declared his candidacy. He finished a distant second behind Schwarzenegger, a Republican.

So far, no high-profile Democrats have declared their intent to run, but Democrats may not want to risk the possibility of having no Democratic replacement candidate on the ballot. Like Bustamante, ambitious Democrats may find the relatively low barrier to place their names on the ballot too inviting. To run in the recall, US citizens who are registered voters need only pay a filing fee around $4,000 or submit approximately 7,000 signatures in lieu of the fee. This low bar led to the circus-like nature of the 2003 recall when 135 candidates entered the race.

Like many things during the pandemic, Newsom’s fate may ultimately ride on the public health conditions at the time of the recall election. If the vaccine rollout puts California much closer to normal, then voters may overlook Newsom’s missteps during some of the darkest times of the pandemic. The economy could also strongly rebound at about the same time, which would also favor Newsom continuing in office. However, if COVID-19 and its variants become more difficult to contain, voters may direct their wrath at Newsom just as they did Davis 18 years ago.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3sRDQSm

About the author

Jeff Cummins – Fresno State University

Jeff Cummins – Fresno State University

Jeff Cummins is a Professor of Political Science and Interim Dean of the College of Social Sciences at Fresno State University. He is the co-author of California: The Politics of Diversity (Rowman & Littlefield) and author of Boom and Bust: The Politics of the California Budget (Institute of Governmental Studies). His research interests include state politics and policy, electoral accountability, and presidential policymaking.

Nice article, Dean Cummins!