Many commentators attributed Donald Trump’s surprise 2016 election victory to the role played by voters heavily affected by deindustrialization, often located in the so-called Midwestern ‘Rust Belt’. In new research which examines voting patterns in counties which have experienced manufacturing layoffs, Leonardo Baccini and Stephen Weymouth find that that these layoffs are associated with greater support for Republican challengers among whites compared to voters of color. They attribute this pattern to whites’ concerns about social and economic status loss in the face of layoffs, concerns which are played on by populist and reactionary candidates like Donald Trump.

Many commentators attributed Donald Trump’s surprise 2016 election victory to the role played by voters heavily affected by deindustrialization, often located in the so-called Midwestern ‘Rust Belt’. In new research which examines voting patterns in counties which have experienced manufacturing layoffs, Leonardo Baccini and Stephen Weymouth find that that these layoffs are associated with greater support for Republican challengers among whites compared to voters of color. They attribute this pattern to whites’ concerns about social and economic status loss in the face of layoffs, concerns which are played on by populist and reactionary candidates like Donald Trump.

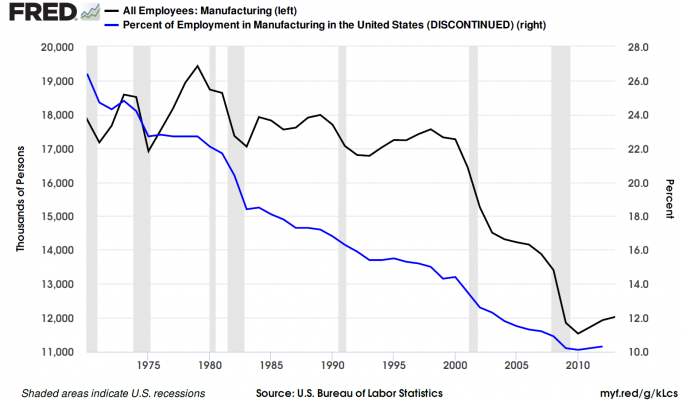

Deindustrialization has decimated the blue-collar workforce in the US. Figure 1 shows that millions of manufacturing jobs have been lost across the US since the 1980s. As documented in books like The Forgotten and Janesville: An American Story, the closure of manufacturing plants has dramatically altered the fate of many once-thriving industrial hubs. Our research examines the effects of deindustrialization on electoral politics.

Figure 1 – De-industrialization in the US

Specifically, we explore how deindustrialization affected voting in three US presidential elections (2008-2016), using county-level data which captures localized manufacturing job losses. Our argument is that responses to what we call economic ‘shocks’ like deindustrialization depend on people’s social identities which come from belonging to a specific group. We argue that some white voters, who perceive themselves as the dominant economic and social group, view deindustrialization as a threat to their social and economic status. As a result, these white voters in affected areas are more likely to vote for reactionary candidates who promise to address economic distress—through trade wars, for instance—and to defend racial hierarchy.

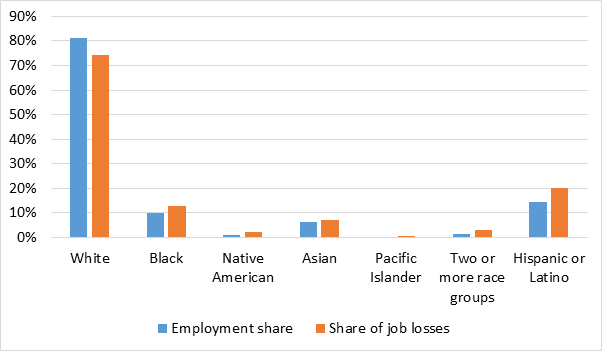

Figure 2 shows the share of employment and layoffs broken down by race/ethnicity at the national level. Note that while white workers account for the largest share, job losses have disproportionately affected workers of color relative to their share of employment.

Figure 2 – Share of employment and job losses by race and ethnicity

How white status anxiety fuels support for populist candidates

Drawing on social identity theory, we expect that white voters’ electoral response to these job losses will differ from the response of voters of color. Whites in localities with more layoffs are more likely to support reactionary candidates such as Donald Trump. In contrast, we expect voters of color in affected areas to be more likely to support progressive candidates who offer policies designed to address economic and racial injustice. While our empirical focus is on the US, we expect a similar pattern to play out in other countries as well.

We test this argument using new county-level data of manufacturing layoffs, which we link to county- and individual-level voting behavior. We find that voters punish Democratic incumbents more for white worker layoffs than for layoffs of people of color. Examining individual-level survey data, we find that layoffs are associated with greater support for Republican challengers among whites relative to voters of color. The estimated effects are particularly large in the 2016 presidential election in which Trump ran an America-First nationalist campaign and explicitly appealed to white racial grievance linked to industrial decline. In contrast, voters of color were likely to support Democratic candidates. These findings indicate that voters of color repudiate the reactionary brand of politics centered on industrial revival and the reaffirmation of racial hierarchy, especially in deindustrializing localities.

“Donald Trump” (CC BY-SA 2.0) by ed ouimette

To explore possible mechanisms at play, we look at how manufacturing layoffs affect attitudes at the individual level. We find that whites are more likely to hold negative views on the general direction in which the country is heading, and on the prospects for individual upward mobility, in areas with higher manufacturing layoffs. Respondents of color living in the same areas do not hold similarly negative views.

Although we conducted our analyses prior to the 2020 election, our research sheds light on the outcome and contains lessons for future elections. In 2016, Trump won states in the US ‘Industrial Belt’ like Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. He lost those states in 2020, as manufacturing job losses had continued apace during his administration. This indicates that even nationalist-populist incumbents are electorally vulnerable if they fail to address deindustrialization and its knock-on effects. Nonetheless, Trump’s popularity among some white voters remained high in 2020, suggesting that the demand for nativist, reactionary politics persists. (Our other research indicates Trump’s COVID pandemic response played an important role in his defeat.) Whether the Biden administration will be able to address some of these grievances may prove central to the Democratic Party candidate’s success in 2024.

Looking beyond the US, support for populist leaders appears entrenched. In exploring the causes of the populist upswing, there is an ongoing debate between material explanations — the role of employment and wages, for instance — and studies highlighting non-material explanations — the role of identity politics and culture. Our research contends that these factors do not operate in isolation. Rather, identity helps explain different political reactions to common economic shocks.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Gone For Good: Deindustrialization, White Voter Backlash, and US Presidential Voting’, in American Political Science Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3xRK1Jr

About the authors

Leonardo Baccini – McGill University

Leonardo Baccini – McGill University

Leonardo Baccini is an Associate Professor in the Political Science Department at McGill University and a Research Fellow at CIREQ. He is a National Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University in the 2020-21 academic year. His research interests are in the area of international political economy and comparative political economy.

Stephen Weymouth – Georgetown University

Stephen Weymouth – Georgetown University

Stephen Weymouth is an Associate Professor and the Dewey Awad Fellow in the McDonough School of Business at Georgetown University. He earned a Ph.D. from the University of California, San Diego. Professor Weymouth studies the political environment of globalization and technological change.