As they try to gain public and Congressional support for their agendas, Presidents have a number of rhetorical tools available to them. In new research Amnon Cavari examines the changing ways that presidents mention their White House predecessors. He writes that contemporary presidents make nearly 300 references to former presidents a year, and that these references are becoming increasingly policy focused. In addition, Presidents are more likely to mention their predecessors from the other party when they are trying to reach across the political aisle.

As they try to gain public and Congressional support for their agendas, Presidents have a number of rhetorical tools available to them. In new research Amnon Cavari examines the changing ways that presidents mention their White House predecessors. He writes that contemporary presidents make nearly 300 references to former presidents a year, and that these references are becoming increasingly policy focused. In addition, Presidents are more likely to mention their predecessors from the other party when they are trying to reach across the political aisle.

In his Inaugural Address on January 20th, President Biden noted that he was taking the same oath of office as President Washington and all presidents since, and quoted President Lincoln to strengthen his promise and commitment to the American people that his whole soul is in “bringing America together, uniting our people, uniting our Nation.” In doing so, the newly elected president connected himself with two who are considered by many to be the great presidents ever to hold the office.

President Biden has continued to reference his presidential predecessors during his time in office thus far – mentioning nearly a third of those who previously occupied the White House (14 presidents) for a total of 100 individual references. For example, more recently, President Biden invoked President Eisenhower, a Republican, to strengthen his appeal of the necessity of an infrastructure investment and—in response to partisan critique—in the role of the federal government in leading it, stating:

…today is the 65th anniversary of one of those significant investments to change the nation. Sixty-five years ago today, President Dwight Eisenhower signed the bill that created the Interstate Highway System. That was the last infrastructure investment of the size and scope of what — the agreement I’m about to talk about today.

– President Biden on Infrastructure Plan, June 29, 2021, La Crosse, Wisconsin

In referencing former presidents, President Biden is no different than his predecessors. How often do presidents use this rhetorical tool? Who do they reference? In what context? And, above all, what is the purpose of these references?

Why presidents reference their predecessors

Only 46 people have held the presidency, most of whom are among the most recognized political figures in the United States. These men are widely viewed as responsible for or are associated with contemporary policies and events and are held as leaders of their parties in the public mind. Referencing former presidents can therefore carry significant weight. Presidents can take advantage of the popular attachments to these men and utilize them in their rhetorical appeals to advance support for policies, provide legitimacy to their presidency, and score political and electoral points.

Given the importance and possible effect of this rhetorical tool, I seek to understand the use and effect of this rhetorical tool. In new research, I examined, together with Ben Yoel and Hannah Lowenkamp, the extent that this tool is used and why.

To further understand presidential references, we systematically assessed all oral mentions of former presidents by presidents from Ronald Reagan to Donald J. Trump, providing us with a robust sample of six presidents that amount to nearly 12,000 individual references to past presidents. We collected information about each reference—date, location, and policy context in which they were made.

References are routine

We find that presidents mention their predecessors routinely and often – on average, presidents make nearly 300 references to former presidents a year. We further find that these references are associated with their routine public appeals—scattered throughout their term in office and increasingly within the context of a particular policy.

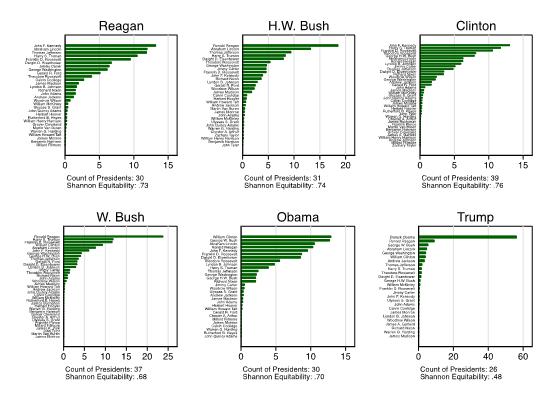

In their references, presidents mention most of their predecessors – from nearly all presidents (Clinton, 98 percent of his predecessors) to about half of former presidents (Trump, 53 percent). But, while they reference many presidents, some receive more attention than others. Presidents tend to reference who most consider to be the great, exemplary presidents—though this has declined over time—and their immediate predecessors—with President Trump as a clear outlier by referencing Barack Obama in more than half of all his references of former presidents. The share of references of each president by each of the six presidents in our sample is summarized in Figure 1 below. Under each panel, we also list the count of presidents each mentions and a measure of diversity in presidents named (0 = full diversity; 1 = all former presidents are named evenly).

Figure 1 – References to previous presidents by six presidents

In terms of the political environment, we find that presidents find electoral value in these references – they make more references during election months – and that associating with former presidents allows them to define their legacy – they make more references during their final months in office. The strategic use of this tool is best revealed, however, when we consider the moderating effect of the political environment on the partisan identity of the president mentioned. We find that while presidents tend to reference presidents from their party, when government is divided (if Congress is controlled by a different party from the president), presidents reference their predecessors from the other party as a way to reach across the aisle. We find that presidents do it more today than in the past.

President Biden sits under three portraits in the Oval Office – FDR, Alexander Hamilton (not a former president), and Thomas Jefferson

“P20210602AS-1491” by The White House is United States Government Work.

Beyond the generalizations we draw from the systematic analysis of references, we suggest that our findings tell a story of its own that can help citizens and academics understand deeper levels of presidential rhetoric and the role of history in it. A rich body of work demonstrates that presidents routinely appeal to the American people in an effort to set the policy agenda, mobilize public support for their policies and define how they are viewed by the American people. We show that in these appeals, presidents engage with the immediate and distant past. They associate themselves with the previous holders of the office and, in doing so, take part in defining the changing role of the office and of the role of history in understanding the political process.

The decline in presidential references to exemplary presidents may indicate a change in the role of history and cultural identity in the public sphere. The increasing trend of references to presidents from the other party, especially during divided government, may indicate the difficulty of making a rhetorical appeal to unity during our current polarized politics. And the upward trend of referring to past presidents in the context of policy agendas, further suggests a change in the nature of presidential rhetoric that may become more constructive.

- This article is based on the paper, “In the Name of the President” in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2VqFXBB

About the author

Amnon Cavari – Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya

Amnon Cavari – Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya

Amnon Cavari is assistant professor at the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy, and Strategy at the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, head of the American Public Opinion toward Israel (APOI) research lab, and co-chair of the Policy Agendas Project at IDC. Dr. Cavari is the author of The Party Politics of Presidential Rhetoric (Cambridge, 2017) and of several journal articles about the US presidency and public opinion.