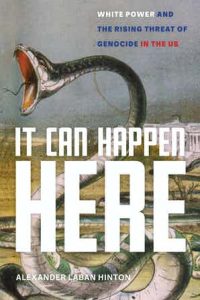

In It Can Happen Here: White Power and the Rising Threat of Genocide in the US, Alexander Laban Hinton challenges the myth of exceptionalism that has led many to believe that genocide cannot happen in America, exploring contemporary white power extremism in the US. This nuanced and noble account encourages readers to carefully and critically attend to the longer histories and structures within which racism, hate and white supremacy are embedded, writes Sabah Carrim.

It Can Happen Here: White Power and the Rising Threat of Genocide in the US. Alexander Laban Hinton. NYU Press. 2021.

‘It has happened here before,’ writes Alexander Laban Hinton. ‘It came close to happening during the Trump presidency. Some say it did happen on the southern border. And it can happen again’ (21). ‘It’ refers to genocide, and Hinton’s book It Can Happen Here: White Power and the Rising Threat of Genocide in the US is an attempt to bust the myth of American ‘exceptionalism’ that has led many to believe that genocide cannot happen in the United States.

‘It has happened here before,’ writes Alexander Laban Hinton. ‘It came close to happening during the Trump presidency. Some say it did happen on the southern border. And it can happen again’ (21). ‘It’ refers to genocide, and Hinton’s book It Can Happen Here: White Power and the Rising Threat of Genocide in the US is an attempt to bust the myth of American ‘exceptionalism’ that has led many to believe that genocide cannot happen in the United States.

The book chronicles a momentous period in US history, where given the pressures of racist and antisemitic outcries, riots and mass shootings, including the events of Charlottesville and Tree of Life, novel ways had to be sought by professors such as Hinton to incite students — the leaders of tomorrow — to behave differently from the civilians and movers who lent support to the distortions and perversities that Trump and his administration introduced in a four-year reign. Much could be deplored about the behaviour of people during that period: how thinking, reasoning, the application of critical skills — signs once deemed the pride of the US and the reason for its primacy — seemed suddenly amiss.

While Hinton’s stand against the modus operandi of the Trump administration is evident, true to his calling as an academic and a thinker, he looks beyond the war of political partisanship that has divided the country. He suggests that our approach to understanding and critiquing — whatever our political allegiance — is often flawed, for it is reductive and simplistic.

He starts by uttering a word of caution about laying the entire blame on one person and one party. The support showed to Trump and his administration was but a sign of a larger systemic problem, he writes, for ‘white supremacy has been around a long time. If we view events like Tree of Life and Charlottesville as exceptional, we lose sight of how they are connected to the longer history of white supremacy in the US’ (94). In the same vein, he guides his students away from making general statements in their criticism of the aforementioned events. This is the message that lies at the heart of the book and in pointing it out, Hinton veers attention away from a reductionist understanding of both phenomena and people.

Image Credit: Crop of Photo by little plant on Unsplash

During his first teach-in at Rutgers University, as recorded in the book, Hinton discusses the meaning of ‘Critical Analysis’. Analysis is from the Greek term, analusis, meaning to ‘unloosen’. ‘Analysis involves an unraveling, taking something apart to understand how it is composed from its constituent parts’ (30). One gleans from what follows in class that one should not jump to quick conclusions and should avoid what the ‘haters’ do, indicative of impulsiveness and lack of thought: this includes name-calling, mud-slinging, indulging in character assassination.

These were the very traits displayed by Trump before and after the presidential elections, through his employment of personal attacks such as ‘Crooked Hillary’ and ‘Sleepy Joe’, or in calling Elizabeth Warren ‘Goofy’. These all resonated furthermore with the events in Charlottesville when white supremacists made monkey hoots and called black people ‘savages’. Hinton argues that there needs to be a shift away from this reductive method of thinking, acting and speaking, and goes a step further by encouraging his students in the teach-in to be more conscious of the complexity of history, of the need to avoid sweeping generalisations about phenomena and people. This includes making sure that criticism of the actions of Christopher Cantwell, one of the main instigators of the Charlottesville riots, goes beyond just one or two-word statements such as ‘Crying Nazi’, ‘demented, ‘racist’, ‘power hungry’ or ‘twisted’ (54).

Thus to have the support of ‘numbers’ in a classroom setting and therefore be on the ‘right’ side is insufficient. The why of our choices is important, Hinton emphasises, and if we members of civil society restrict ourselves to superficial intellectual engagement, then no real difference exists between the forces that empower ‘haters’ and white supremacists and those that empower the counter-movements we set up. Hinton’s understanding of this tautology is most evident when he responds with ‘More one-word explanations’ (54) to the reactions of his students. He goes on to add:

The key thing is to think critically about whatever term we decide to use and to not let individualizing one-word explanations divert us from the longer histories and structures in which racism, hate, and white supremacy are embedded (58).

In the absence of deeper intellectual engagement, it is easy to envisage long-term consequences as the ones enunciated in Albert Camus’s 1951 essay The Rebel: that the phenomenon of oppressors oppressing the oppressed will naturally be followed by a reversal of roles (of the oppressed eventually oppressing former oppressors), if the revolution in between these two processes is not genuine and meaningful and barely scratches the surface of the struggle. Friedrich Nietzsche, the philologist, adopted a similar stance throughout his work, singling out the flaw in scholarship to be the oversimplified grasp of concepts — their desecration—especially when they were not analysed and understood amid the evolving dynamics of time and space. The concept and idea of ‘democracy’ is one example, and in Hinton’s book, various movements of white supremacy are detailed, revealing the currency this form of radicalism has gained, and the variety of instances in which this ideology has undergone minor, but important, modifications to its aims and role in US history.

Hinton’s second teach-in is focused on finding out the origin of the hatred harboured by ideologues and the radical. For this, in his capacity as a Cambodia expert, abundant references are made to the atrocities committed during the Khmer Rouge era, focusing on theories such as ‘modified intentionalism’ and ‘cumulative radicalisation’ to explain how genocidal policies such as Nazi Germany’s ‘Final Solution’ came to fruition (67). It is proposed that perpetrators of genocide do not necessarily harbour plans of mass extermination at the beginning of their radical programme; that these often mark a culmination of a series of ostensibly ‘milder’ and not-so-effective projects. Seemingly innocuous actions matter too, he adds, and should not be ignored in assessing the possibility of an imminent genocide.

Hinton therefore warns against a reductive understanding of how genocides are perpetuated: ‘Genocide is a process’, he writes, ‘a flowing river that has cross-currents and is fed by tributaries and streams’ (70). He also directs us away from closing in on the individual, the fanatic who ‘starts fires’, and instead asks us to consider ‘structures that mediate human agency, including the forces of power and history’ (71). It Can Happen Here is an admonition to us not to overlook the budding signs of an impending genocide; to remember that while there are certain identifiable prerequisites for one to take place, unidentifiable ones should not distract us from its possibility. Armed with an understanding of how genocide is perpetrated through a coming together of known and unknown forces and elements, the discussion in class is centred on how close the US came to experiencing one during the chaos endured under Trump’s presidency.

Fortunately Hinton does not leave us with problems, but has a solution too: A Truth Commission on White Supremacy and Its Legacies that would extend beyond the aims of the reparations bill following the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, and open a discussion about the perpetrations of white nationalists and supremacists in a past yet unaccounted for.

The understanding Hinton provides to events marking US history is objective, nuanced and noble, and teaches us readers that in seeking to define and judge phenomena and people intelligently, accurately and critically, these must necessarily be placed in the continuum of time and space. The essence of Hinton’s teach-ins bears a reminder of Goethe’s words on the importance of studying history to truly appreciate who and where we are today: ‘He who cannot draw on three thousand years is living from hand to mouth.’

- This article originally appeared at LSE Review of Books.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/37r1BYI

About the reviewer

Sabah Carrim – Texas State University

Sabah Carrim has a PhD in Genocide Studies and Prevention with a focus on the Khmer Rouge era. She has also authored two novels, Humeirah and Semi-Apes, and short stories that have been selected in various international short story writing competitions. She sits on the Advisory Board of the International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) as Emerging Scholars Representative. Sabah is currently recipient of the W. Morgan and Lou Claire Rose Scholarship for a MFA in Creative Writing in Texas State University in the United States.