In The International LGBT Rights Movement: A History, Laura A. Belmonte describes the twists and turns that have characterised the history of the international LGBT rights movement, focusing primarily on activism and mobilisations in North America and Europe. The book’s key message is that while efforts to achieve equal rights for LGBT people persist, there remains a long road to full equality and dignity, writes Kanav Narayan Sahgal.

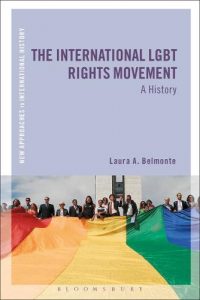

The International LGBT Rights Movement: A History. Laura A. Belmonte. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people across the world share interlocking histories of persecution and violence. In The International LGBT Rights Movement: A History, historian Laura A. Belmonte takes her readers on a transnational journey across space and time to map out the contestations, challenges, victories and losses faced by courageous people who have shaped the trajectory of the LGBT movement in their respective regions and, over time, across the rest of the world.

Belmonte uses select historical figures, organisations, events and moments to illuminate the critical junctures of the LGBT movement from the mid-nineteenth century up until the time of the book’s publication in 2020. The book greatly benefits from Belmonte’s use of both primary and secondary data, as well as her meticulous deployment of particular types of archives that were hitherto ignored by international relations scholars (such as resources from IHLIA LGBT Heritage at the Amsterdam Public Library, the Hall-Carpenter Archives at LSE Library and the ONE Archive at the University of Southern California, to name a few).

The book is divided into eight parts, including an introduction, six chronologically arranged chapters and a conclusion. In her introduction, Belmonte sets the stage for the transnational LGBT movement. Here, she provides a big picture overview of various facets of LGBT organising – the challenges, achievements and complexities. The precise nature of these complexities is explored in subsequent chapters.

Photo by Teddy Österblom on Unsplash

In the introduction, Belmonte also clarifies two important things. First, that this book primarily focuses on the experiences of activists in Europe and North America (3); and second, that although the book aspires to highlight the stories of people embodying all identities within the LGBT spectrum, most of the book centres on the activisms of gay men. This, according to Belmonte, is partly due to the lack of rich historical data on lesbians, bisexuals, transgender people and others who fall under the umbrella of ‘queer’.

Interestingly, the word ‘queer’ rarely appears in the book; and whenever it does, it is not historicised adequately. This is a rather stunning oversight because some scholars would argue that the very introduction of ‘queer’ as a political category within the LGBT movement was significant because it intentionally destabilised heteronormative and cis-normative notions of sexual orientation and gender identity, so much so that ‘queer’ also challenged essentialist identities like ‘gay’ and ‘lesbian’. The sociological implications of these identities are rarely questioned in the book and neither are other problematic notions such as the prevailing human rights discourse around LGBT rights and the increasing corporatisation of the global LGBT movement. On the other hand, issues like the politicisation of LGBT rights and the uncanny contemporary misuse of LGBT rights to fuel Islamophobia, nativism and homonationalism are sufficiently highlighted (196-97).

From Chapter One (‘Origins’) to Chapter Six (‘Global Equality, Global Backlash, 2001-20’), Belmonte takes her readers on an exhilarating journey of love, loss, pain and joy by mapping out the twists and turns of the LGBT (primarily gay rights) movement. A couple of things stand out in this journey. First, that the advancement of LGBT rights rested on the shoulders of a few brave people who – in some cases advertently and in other cases, inadvertently – risked their lives, livelihoods and reputation to directly challenge unjust laws, policies and beliefs.

Some of these luminaries included Jeremy Bentham, the British philosopher who wrote in support of sodomy in 1785, a time when the terms ‘homosexual’ and ’heterosexual’ didn’t even exist. Belmonte also discusses the writer Oscar Wilde, who was embroiled in a highly publicised gay sex scandal that led to his arrest and eventually degraded his mental, physical and emotional health. She also mentions Magnus Hirschfield, a Jewish-German physician who Belmonte rightfully calls ‘one of the most significant activists in the history of the International LGBT rights movement’ (35).

There were, of course, plenty of other thinkers and activists from other parts of the world who also challenged heteronormativity and cis-normativity in their own ways, oftentimes drawing inspiration from one another. Some of these bonds were local, such as the camaraderie between Harry Hay, Rudi Gernreich, Bob Hull, Charles Rowland and Dale Jennings, which led to the setting up the first homophile organisation in the US in 1950, The Mattachine Society. Others were transnational, such as the relationships between local and regional gay-centric magazines with their international contributors and readers in the Cold War and post-Cold War era.

The other thing that stood out for me was how LGBT people were persecuted everywhere – from all sides, across space and time, by different actors for a range of different reasons! Perhaps the most poignant example of this was displayed in the first half of the twentieth century when homosexuals were not only viciously persecuted by the Nazis in Germany, but also by fascists in Italy, the communists in the Soviet Union, the conservatives in America and even the Allied forces in the post-war period.

More interestingly, the justifications for oppression were similar in some cases and different in others. For instance, the Nazis condemned homosexuality because they saw it as ‘un-German’ and a threat to the Third Reich’s crusade of achieving moral purity. These views did not change immediately in post-war Germany, when the newly formed government at that time also believed that homosexuality was a threat to the then newly created German nation. For these reasons, this government continued to uphold Paragraph 175, a section in the German legal code that criminalised consensual and private same-sex activity between men. Paragraph 175 was the same law that the Nazis also used during their rule. Communist nations, on the other hand, associated homosexuality with ‘bourgeois degeneracy’ (75), while anti-communists associated homosexuality with ‘communist subversion’ (83). In short, LGBT people had few, if any, allies.

Despite facing social, legal, cultural, religious, political, medical and moral challenges, LGBT people around the world continued to fight back. Towards the end of the book, Belmonte cogently describes how the rapid formation of transnational solidarity groups and the slow creep of globalisation eventually effectuated slow but steady positive legal and political changes.

However, Belmonte ends on a cautious note. She reminds us that, as of 2019, 123 out of the 193 member states of the United Nations had legalised consensual same-sex activity and 26 of them had legalised same-sex marriage (1); however, 68 countries still criminalised consensual same-sex activity and 32 had ‘morality laws’ that restrict freedom of expression relating to sexual orientation and gender identity.

Thus, the international LGBT rights landscape remains hotly contested and it will, unfortunately, continue to be this way for years to come. And while a lot has changed – laws, attitudes, beliefs and perceptions – what has not altered is what I like to call ‘the spirit of inter-generational and transnational LGBT solidarity’ that spans across time and space and continues to be relevant today. It is through the powerful stories of resistance and despair highlighted in this book that one learns to value the hard work and sacrifices of those LGBT activists who set the foundation stones of the modern international LGBT movement.

- This review first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3D1ZloH

About the reviewer

Kanav Narayan Sahgal – Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, India

Kanav Narayan Sahgal (Pronouns: He/Him) is, as of September 2021, the Samvidhaan Fellowship Programme Manager at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, India. He is also a Post-Graduate of Development Studies from Azim Premji University, India. He identifies as queer for personal and political reasons and writes about social exclusion and marginality from an interdisciplinary sociological perspective. For any questions or queries, reach out to him on LinkedIn or via email at sahgalkanav@gmail.com. All views expressed are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views of his organization.