In Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin, Matthew Soules offers a new account of architecture under 21st-century capitalism, showing how buildings are bound up in the rise of financialisation. This compelling, chilling book offer valuable insights into both political and architectural theory, finds Monika Dybalska.

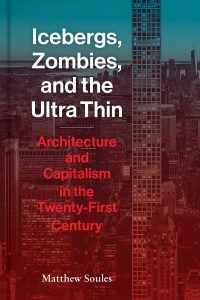

Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century. Matthew Soules. Princeton Architectural Press. 2021.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Matthew Soules’s Icebergs, Zombies, and the Ultra Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century aims to provide a comprehensive account of the architectural order of 21st-century capitalism. The author’s declared inspiration behind the book is the 2007-2008 financial crisis, which not only exacerbated economic inequalities but also underscored the rise of ‘financialisation’ — a process in which financial markets, assets and instruments gain increasingly more influence over society. While financialisation, and its milieu, finance capitalism, have largely determined both the lived experience of the general population and the theoretical landscape of today, its links to architecture remain unexplored.

Soules’s work introduces the unique concept of ‘finance capitalist architecture’ and conducts an in-depth analysis of its possible implications. By characterising contemporary architecture and urbanism as specifically financialised phenomena, the author explores the interplay between buildings and finance capitalism, examining both the architectural and socio-economic aspects of the contemporary.

According to Soules, finance capitalism constitutes a state of affairs in which speculation replaces production, thus placing profitable financial instruments on a pedestal and casting aside the material realm of commodities. The pursuit of intangible, referenceless profit gives primacy to immateriality and fluidity.

Fluidity itself is a key characteristic of the ever-shifting nature of capitalism, and the speculative core of finance capitalism brings it to full fruition. Bearing this in mind, one might find it challenging to incorporate architecture, in its wholly solid, stationary state, into the liquidity of financial instruments. In Soules’s view, however, architecture is precisely what plays a crucial role in the reproduction of financial fluidity, thus transforming both itself and finance capitalism as a whole.

Photo by Chris Barbalis on Unsplash

In his project to thoroughly characterise finance capitalist architecture, Soules positions himself within Marxist thought, both in its classical and more contemporary varieties, while framing it in the 21st-century context. The most pronounced interpretative framework from which Soules draws is that of Frederic Jameson, whose writings on capitalism and architecture were highly influential in the second half of the twentieth century.

While Soules agrees with Jameson’s assessment of architecture as a powerful actor in late capitalism, he diverges from Jameson’s conceptual separation of capitalism and architecture. In Jameson’s view, architecture is naturally informed by capitalism but remains a primarily aesthetic phenomenon, thus retaining significant autonomy from the workings of the economic order. Soules’s assessment of finance capitalist architecture, however, posits that architecture cannot claim meaningful autonomy from capitalism and that the two phenomena need to be jointly regarded for an accurate, in-depth analysis to emerge.

Soules’s book is an original work whose far-reaching scope and bold points make it a valuable contribution to the fields of architectural theory and political critique. Its strengths are its methodological approach and critical adaptation of the work of Jameson that are conveyed by the eponymous (and fittingly dramatic) concepts. By introducing the term ‘zombie urbanism’ — the rise of underoccupied secondary homes acting as investment properties — and its even more overt form, ‘ghost urbanism’, Soules delivers a trenchant characterisation of finance capitalist architecture as the space of crisis. In contrast to Jameson’s approach, Soules regards these crisis spaces as a necessary outcome of the capitalist mindset and links them to the primacy of speculative investments that impair the solidity and materiality of housing.

Furthermore, Soules succeeds in showing that architecture acts not only as a result of finance capitalist principles, but also as their enabler, thus cementing the conceptual bond between capitalism and architecture. In his account of the forms of financialised architecture, Soules solidifies finance capitalist housing’s status as a mass stock offering. One example is the case of ‘iceberg homes’, where the ultra-rich use extravagant basement extensions to store even more wealth while adhering to the zoning regulations that prevent the excessive expansion of houses. By conducting case studies of spatial profit optimisation and analysing the trends in property investment, Soules convincingly argues that architecture’s role in weaving the fabric of capitalism is not incidental.

Another strong point of the book is its skilful reconciliation of lived experience and more abstract universalism. While Soules explicitly states that he draws from traditionally universalist Marxist thought, his commitment to emphasising the plurality of today’s world allows for a non-totalising, more inclusive approach to architectural and political theory. His work permits a conceptual common ground by putting forth abstract ideas such as ghost urbanism and liquidity, but also stressing the importance of locality and the differences between cases. As a result, the book arrives at a comprehensive theory of finance capitalist architecture but does not assume completeness, settling instead on further exploration of the ever-changing capitalist reality.

Despite the significant value of the case study approach, the book’s structure impairs its conceptual organicism, often concealing the main argument and making the conclusions appear less pronounced than might be desired. Chapter Eight, dedicated to the trend of philanthropic urbanism, uses the example of Vancouver House’s ‘one for one’ initiative to explain the allure charity holds for property investors. The initiative, whereby every purchase of a housing unit results in the building owner gifting another unit to a person in need, is illustrative of the sinister aspect of philanthropy and acts as an insignificant, temporary solution designed to improve the developer’s image, lure investors and bring more clients.

While this chapter provides a sound critique of capitalist charity and introduces the phenomenon of ‘spatial philanthropy’, it does not fully explore the spatial and architectural upshots of ‘giving back’ under late capitalism. The concept of ‘spatial philanthropy’ is not afforded any unique characteristics, which may limit its viability and explanatory power. The seemingly accidental position architecture takes in ‘spatial philanthropy’ obscures the previously established role architecture plays in finance capitalism, appearing to reduce it once again to a symbol of capitalism rather than its active agent.

This relates to a lack of clarity regarding the key argument; while the book’s scope, structure and methodology suggest that it aims to provide a comprehensive, in-depth analysis of finance capitalist architecture, the occasional lack of organisational consistency makes it more akin to a loosely connected series of several different analyses. A clear, unifying conclusion would help finance capitalist architecture to take a marked shape.

Overall, however, the book succeeds in characterising contemporary architecture as a finance capitalist phenomenon and provides valuable insights into both political and architectural theory. This success is exemplified in the final chapter, where the interplay between architecture and capitalism fully comes into the light, blurring any remaining distinctions between them. Soules’s assertion that ‘the architecture of finance capitalism is a real abstraction [functioning] as a device at the liminal space between material, concrete existence and the seemingly mystical, abstract, complex, and immaterial realm of finance’ brings to the fore the true nature of finance capitalist architecture — one of an abstract financial functionality, immaterial and incapable of providing human shelter. Despite some organisational flaws, Soules’s book remains a compelling, chilling read which attacks the comforting notion of home, forcing the reader to find their bearings and prepare the ground for a different, concrete future.

- This review first appeared at LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3ec2706

About the reviewer

Monika Dybalska – University of Amsterdam

Monika Dybalska is a recent graduate from the Research Master in Philosophy programme at the University of Amsterdam. Her research interests consist of philosophy of architecture, critical theory and hauntology, and her Master’s thesis, entitled The Cosy Haunting: A Hauntology Of The 21st Century Popularisation Of Hygge, concerned the relationship between architecture, hauntology and capitalism.