Social media sentiment has become a powerful force across most aspects of society, and state and local government is no exception. In new research, Justin Marlowe tracks the social media output of state and local finance officials from 2014 to 2020, finding that their sentiment became more negative following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. He writes that these negative sentiments could lead to real consequences for local government finances.

Social media sentiment has become a powerful force across most aspects of society, and state and local government is no exception. In new research, Justin Marlowe tracks the social media output of state and local finance officials from 2014 to 2020, finding that their sentiment became more negative following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. He writes that these negative sentiments could lead to real consequences for local government finances.

Comets, Facts, and Feelings

The new hit film Don’t Look Up is about a comet on a collision course with earth. It features a bevy of A-list stars careening through some of the most memorable satire in years. Oddly enough, it also reveals some compelling lessons for state and local government finance. My new research echoes these lessons.

With apologies to the comet – an allegory for climate change – Don’t Look Up is actually a story of how celebrity worship, social media, and opinion journalism bring out the most credulous element of our citizenry. In its opening scenes, scientists present a wonky but definitive story of when and where the comet will arrive. But as often happens with complex and foreboding issues, a vague cadre of elite “influencers” rearrange that story around self-serving narratives like pride, nostalgia, and sanctimony. Attitude overtakes analysis, everyone is distracted and paralyzed, and (spoiler alert) the comet wins.

Don’t Look Up shines a bright light on our tendency to filter facts through feelings. Social scientists have documented this tendency for decades, consistently showing that “sentiment” can produce a variety of otherwise unexpected behaviors. For instance, investors’ feelings about future stock prices have a surprisingly large effect on the prices of stocks that are otherwise difficult to predict. Consumers’ feelings about the current economy predict their future spending, even though economic theory says they shouldn’t. Smokers are more likely to quit if they think a growing share of the public disapproves of cigarette use. And so forth.

Sentiment and Social Media

Social media has transformed sentiment into a focused and powerful force. Sentiment toward a particular person, company, or social movement can change in minutes but leave behind permanent financial and reputational consequences. “Game Stop Mania” is a vivid recent example. If a few posts on the “wallstreetbets” subreddit can cause a company to gain or lose billions in an instant, it’s clear that all of today’s leaders must keep close tabs on public sentiment toward their organization.

State and local governments are no exception. Much of their work is diverse, highly technical, and performed out of sight. This is particularly true for state and local government finances. Where public money comes from and where it goes are shaped by an extraordinarily complex set of financial policies and practices. Citizens can engage that complexity by reading hundreds of pages of budgets and financial statements. Or, they can lean on sentiments like “wasteful” or “suspicious.” The path they choose has important implications for taxing, spending, and trust in government.

Previous work has looked at the sentiment conveyed through local government financial statements and budget narratives. But so far no one has asked: Is there a discernable public financial sentiment in social media. And if there is, does it matter?

Trends in Public Financial Sentiment

I took up these questions in a recent study. Fortunately, state and local finance officials are no strangers to social media. As of January 2021, there were 73 official Twitter accounts maintained by US state officials with the title “Treasurer,” “Chief Finance Officer,” “Comptroller,” “Auditor,” or “Budget Director.” There were also 33 accounts maintained by officials with similar titles in the 25 largest (by population) US cities and counties. From 2014-2020, these 106 officials tweeted more than 125,000 times.

I analyzed those tweets using a methodology first developed to uncover the financial sentiment conveyed through public companies’ required financial disclosures. That methodology classifies financial words into one of five mutually exclusive sentiment categories: “constraining,” “litigious”, “negative”, “positive,” and “uncertainty.” The tweets examined here contained 1,836 individual financial sentiment words, and those words appeared a total of 64,735 times.

Photo by Claudio Schwarz on Unsplash

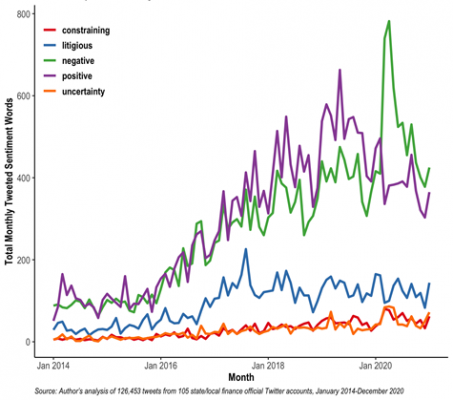

Figure 1 below illustrates the patterns in those words over time. It shows, first and foremost, that the volume of sentiment words overall, and of positive and negative sentiment words in particular, has grown considerably over time. In mid-2016 there were roughly 200 positive and 200 negative words tweeted each month. By mid-2019 there were consistently more than 500 positive tweeted words and 400 negative tweeted words.

Figure 1 – State and Local Public Finance Sentiment, 2014-2020

Perhaps not surprisingly, that ratio of positive to negative reversed as the COVID-19 pandemic took hold. Negative tweets surged starting in March 2020 and then outnumbered positive words for the rests of 2020. Prior to COVID-19, words like “happy,” “honor,” and “improve” drove the positive sentiment. After COVID-19, finance officials used words like “fraud,” “abuse,” and “investigation” much more often, and that drove a sharp increase in negative sentiment. It’s also worth noting that “uncertainty” and “constraining” were mostly unchanged, despite the obvious uncertainty and new constraints that accompanied the pandemic.

These findings suggest there is, in fact, a discernable state and local public financial sentiment, and it responds predictably to key environmental factors.

Negative sentiments might lead to less investment

Does this sentiment have practical consequences? There’s reason to think it may. Some early scholarly work shows that bond investors shy away from governments with persistently negative financial disclosures. There’s similar evidence among municipal finance practitioners. Rosebud Strategies – an investment advisory firm – has developed a Municipal Credit Diffusion Index that tracks public sentiment toward states and localities revealed in social media. Rosebud’s internal modeling shows that interest rates on municipal bonds tend to increase when their Index turns more negative. All this suggests shifts in sentiment can have real financial consequences for states and localities.

We have much to learn going forward. New sophisticated textual analysis tools can refine how we measure public financial sentiment expressed by citizens through social media. We can also better understand why sentiment shifts, and whether policymakers can mitigate or accelerate those shifts. And beyond measuring and predicting it, we also need to take up the tricky ethical question of whether state and local finance officials should influence public financial sentiment.

Now that we know public financial sentiment is for real, we need to “just look up” and make it a core topic in the study of state and local finance.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Stories and Sentiment in State and Local Government Finance’, in State and Local Government Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3GBQBXU

About the author

Justin Marlowe – University of Chicago

Justin Marlowe – University of Chicago

Justin Marlowe is a Research Professor at the University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy, where he also serves as Associate Director of the Center for Municipal Finance. An expert on state and local government financial management and budgeting, he is the author/editor of five books including Financial Strategy for Public Managers (with Sharon Kioko), the first open textbook for public financial management.