Millions of Americans rely on safety-net programs such as the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and Medicaid. In recent decades, these programs have been reformed with the aim of better targeting those most in need by creating rules and eligibility assessments. In new research. Ashley Fox, Wenhui Feng and Megan Reynolds find that the introduction of these rules has created substantial barriers and often reduced the enrolment of those who need the programs’ support the most. They argue that if we want needy individuals to access benefits, then we need to make it easy for them to do so by relaxing or removing the burdensome rules that serve as barriers to access.

Millions of Americans rely on safety-net programs such as the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and Medicaid. In recent decades, these programs have been reformed with the aim of better targeting those most in need by creating rules and eligibility assessments. In new research. Ashley Fox, Wenhui Feng and Megan Reynolds find that the introduction of these rules has created substantial barriers and often reduced the enrolment of those who need the programs’ support the most. They argue that if we want needy individuals to access benefits, then we need to make it easy for them to do so by relaxing or removing the burdensome rules that serve as barriers to access.

The logic of “means-testing” in safety-net programs seems simple and straightforward – social spending should go towards those who need it and not to those who can afford to pay out of pocket. However, in our recent research, we largely find the opposite: that the nearly three-decade quest to better target benefits to only those most in need in the United States has ironically made benefits harder to access in ways that may systematically exclude those who need them the most.

While the principle that public spending should be targeted to those most in need sounds logical, in practice, means-testing social programs requires the development of an elaborate set of bureaucratic rules and procedures to determine eligibility, prove the need is involuntary and that the benefits are “deserved.” An emerging body of research has begun to shed light on the ways that these burdensome administrative rules add social costs to claiming benefits in ways that are counterproductive. We show how varying degrees of burdensome administrative rules in three of the US’s largest safety-net programs- cash assistance (aka, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF), food assistance (aka, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP), and public health insurance (aka, Medicaid)- have been designed in ways that either restrict or enhance access.

How rules can curtail a program

Cash assistance (TANF) serves as a cautionary tale of how excessive rule burden can gut a program and increase the cost of claiming beyond a recipient’s willingness to pay. The US once had a vibrant cash assistance program- Aid for Families with Dependent Children. Millions of women and children living in poverty were kept afloat by the program. In 1996, these same women and children became the targets of social reform efforts that used racist dog-whistles to claim that “welfare queens” were living on the dole and needed to be disciplined into moving from welfare to work. The funding for the program was turned into a block grant that was given to states enabling them to essentially design their own program with little federal oversight. What emerged was a Frankenstein-like assortment of program rules that vary considerably from state to state. These rules include various types of work requirements, behavioral conditionalities and strict definitions of who is considered a member of a household. Enrollment in cash welfare plummeted.

Welfare reform also severed the previously integrated enrollment mechanisms between cash assistance, food assistance and public health insurance, as well as adding additional barriers to immigrants otherwise eligible for social services. Enrollment in these other programs began to fall as well as they became harder to access. However, whereas cash assistance got tougher to access, over time, policymakers have endeavored to make it easier for families in need to access food assistance and Medicaid by easing administrative burden.

Image credit: USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

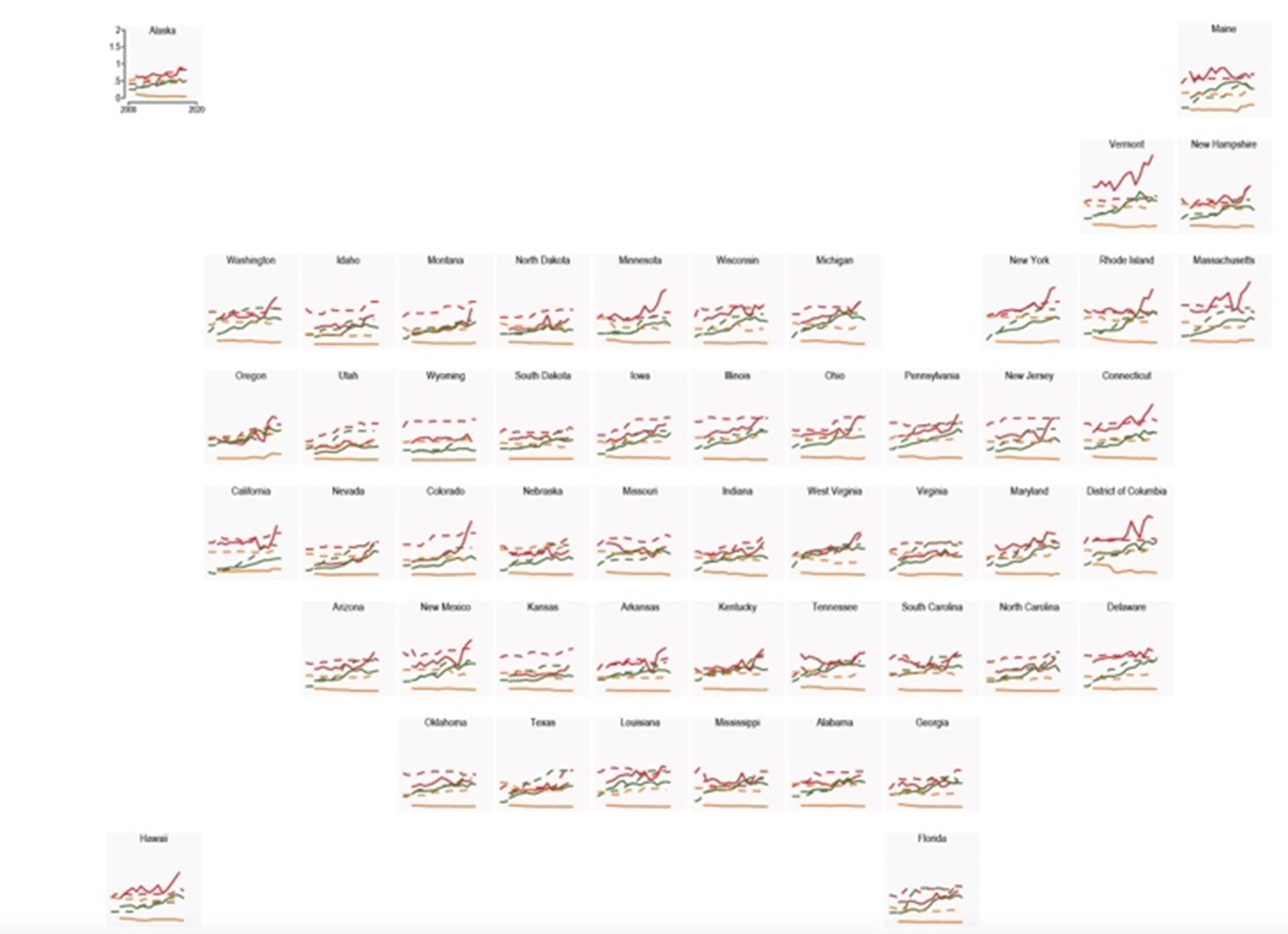

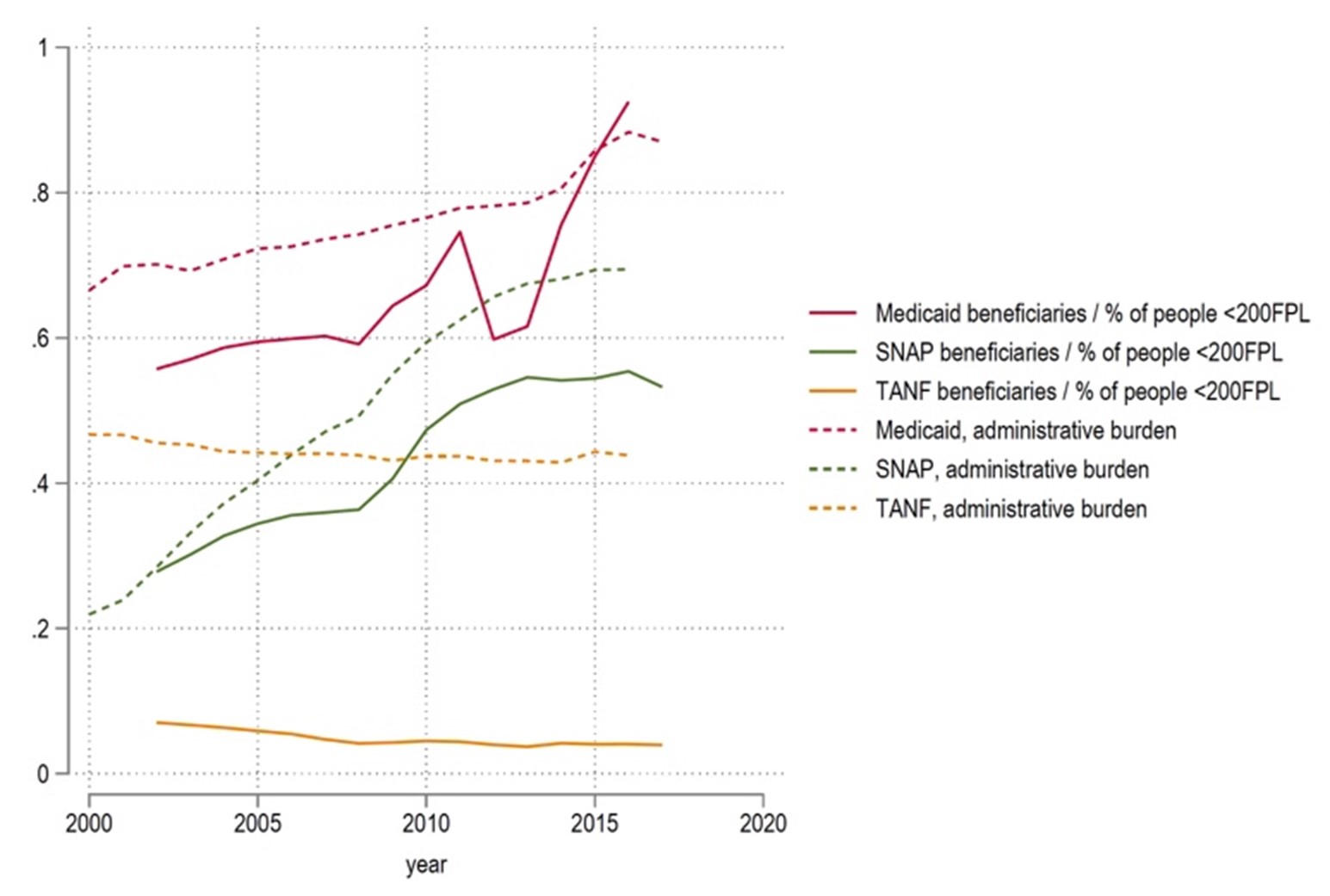

We show how the introduction of program rules that affect learning costs (how easy it is to find out about a program and enroll), compliance costs (how easy it is to remain enrolled) and psychological costs (e.g., how stigmatizing it is access benefits) have affected program use by needy Americans over time (see Figure 1). We find that each program contained numerous rules that limit program access and impose substantial costs, though generalized cash assistance (classic welfare) remains the most burdensome with the greatest number or rules and lowest enrollment among the needy. We additionally find that rules that put the burden of proof on the individual to demonstrate their eligibility, rather than assuming they are eligible until proven otherwise (what we term “innocent until proven guilty”) reduces benefit uptake.

Relaxing rules has led to rising enrolment

To give a few concrete examples of program rules that can ease rule burden, many states have relaxed “asset tests” requiring extensive resource verification beyond documentation of income, as well as replacing stigmatizing paper “food stamps” with an electronic benefit card similar to a credit card and removing a requirement that applicants get fingerprinted. For public health insurance, states have begun allowing children and pregnant women to be enrolled on the spot with just a simple statement of income and allowing eligibility to be verified later as well using information from program participation in other areas to assume eligibility. These and other rules, including those that relax recertification requirements and promote continued coverage, have contributed to rising enrollment among low-income individuals across states over time in food assistance and Medicaid whereas enrollment in cash assistance, which has persisted in its rule burden over time, has stagnated and declined (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Trends in program participation in Medicaid, SNAP, TANF, and administrative rules

Previous research has found that individuals with the fewest resources face the highest burdens in claiming benefits, suggesting that those who are excluded may in fact be the most vulnerable. Paradoxically, in the quest to make sure that only those in need are accessing benefits, policymakers increase the chances of excluding those very same individuals.

Concerningly, policymakers in the United States are currently trying to replicate the experience with cash assistance by putting forward legislation that would block grant food assistance and public health assistance as well. Understanding how means testing produces rule burden can assist policymakers in considering ways to reverse the burden of proof required to access benefits, or even move away from means-testing towards more universalistic programs. The implications of this research suggest that if we want needy individuals to access benefits, we need to make it easy for them to do so by relaxing or removing burdensome rules that serve as barriers to access.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The Effect of Administrative Burden on State Safety-Net Participation: Evidence from SNAP, TANF and Medicaid’, in Public Administration Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3PxrM3J

About the authors

Ashley M. Fox – Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy

Ashley M. Fox – Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy

Ashley M. Fox is an Associate Professor of Public Administration and Policy at Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy. Her research focuses on comparative health politics of policy, inequality, and health and the effects of social policies on health outcomes. Her recent work explores variations in state safety-net generosity and the effects of administrative burden in safety-nets on program enrollment.

Wenhui Feng – Tufts University

Wenhui Feng – Tufts University

Wenhui Feng is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Public Health and Community Medicine at Tufts University. Her research investigates how state and local health departments shape policies and their effectiveness on individual health. She is primarily interested in policies that work towards the prevention of non-communicable diseases, with a focus on the feasibility and effectiveness of policies.

Megan M. Reynolds – University of Utah

Megan M. Reynolds – University of Utah

Megan M. Reynolds is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Utah. Her research examines health and health inequalities in order to understand processes of stratification and their consequences. She is particularly interested in the role of power, politics, and policy in influencing well-being and in how these factors condition the meaning of individual characteristics, such as nativity and gender, for health.