In new research, Tyson Chatagnier investigates why those who serve in the US military are, in general, more conservative in their political views. Is it because those with more conservative views are more likely to join the armed forces, or because service moves individuals’ views to the right? He finds that while those who claim to have served voluntarily identify as both more conservative and more Republican, but also that the experience of military service tends to move people to the left.

In new research, Tyson Chatagnier investigates why those who serve in the US military are, in general, more conservative in their political views. Is it because those with more conservative views are more likely to join the armed forces, or because service moves individuals’ views to the right? He finds that while those who claim to have served voluntarily identify as both more conservative and more Republican, but also that the experience of military service tends to move people to the left.

The politics of military service

Military veterans have always been a distinct group of voters in the United States, of interest to pundits and politicians alike. Each election year brings a new set of polls, seeking to predict the impact that veterans might have. In recent years, those with prior service broke heavily in favor of Mitt Romney in his 2012 race against President Obama, voted 2-to-1 for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton in 2016, but more narrowly sided with President Trump over Joe Biden in the 2020 election. These numbers suggest that most who serve in the United States armed forces are right leaning, which is largely consistent with both conventional wisdom and previous polling. While those who have served in the military do seem to be systematically different in their political views from those who have not, it is less clear why this is the case.

In the modern era, there are two general schools of thought about the relationship between military service and political attitudes. The first draws upon Republican “ownership” of the national defense issue and the fact that military service has been voluntary for the past five decades. It holds that the individuals most likely to join the armed forces are those that hold conservative political views and are predisposed to voting Republican. We call this the selection hypothesis.

The alternative point of view suggests that there is something special about the experience of military service itself, which can change an individual’s attitudes. The argument here is that individuals may not be particularly conservative or Republican when entering the military, but that they shift rightward because of their service. This may be because the armed forces tend to inculcate patriotism and deference to authority into its members, because recruits seek to emulate their more-conservative leaders within the officer corps, or as we argue, that veterans draw upon this service to establish a unique identity over the course of their lifetime. This proposed phenomenon is known as the socialization hypothesis.

Selection versus socialization

Both stories are backed by compelling theoretical narratives and could conceivably account for the differences that we see. In new research with Jonathan Klingler of the University of Mississippi, our goal was to determine the extent to which each theoretical story explains the civil-military gap. However, the two are immensely difficult to disentangle. To this end, we conducted two waves of the Survey of American Veterans (SAVe). In each wave, we interviewed nearly 2,000 Americans, approximately half of whom reported having served in the US military. While we asked questions about demographic characteristics, political affiliations, and attitudes, we also inquired about two important factors: respondents’ backgrounds and their reasons for joining.

This information allows us to address the selection versus socialization question by comparing respondents with similar backgrounds. To isolate the effects of socialization, for example, we matched veterans to comparable non-veterans on eleven important predictors of selection, including parental service, age, and proximity to a military base when growing up. The idea here is that both individuals would be similarly predisposed to volunteering. Therefore, any differences that we observe are more readily attributable to socialization. We then went a step further, comparing veterans who claim to have been drafted or influenced by the draft (known as “reluctant volunteers”) to similar veterans who report having freely volunteered. In this case, if the general conditions of service are similar, then any differences that exist ought to be attributable to selection.

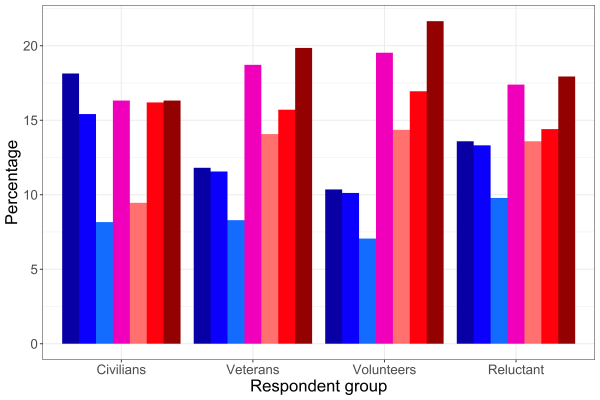

Figure 1 shows the percentage of SAVe respondents that fall into each of seven categories, ranging from Strong Democrat (dark blue) to Strong Republican (dark red). The initial breakdown lines up well with the conventional wisdom. Our non-veteran respondents are distributed evenly, with a slight edge to Democrats, while veterans clearly lean Republican. This latter phenomenon is driven by the true volunteers, who are more heavily Republican than draftees and reluctant volunteers. But what explains this difference?

Figure 1 – Party identification across groups

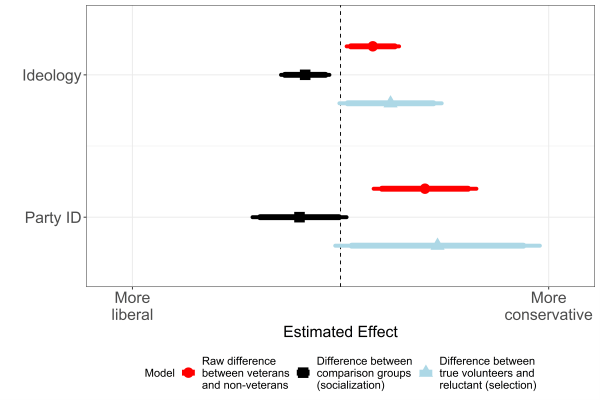

As Figure 2 indicates, both selection and socialization seem to play a role in influencing individuals’ political attitudes. Surprisingly, however, these two components work at cross-purposes. In general, survey respondents with prior military service reported being more liberal and more likely to identify as a Democrat than non-veterans with similar backgrounds. This suggests that contrary to many expectations, the experience of military service tends to move one to the left.

Figure 2 – Estimated effects of selection and socialization

However, when we turn to looking at a subsample consisting only of veterans, we find that those who claim to have served voluntarily identify as both more conservative and more Republican than similar conscripts and reluctant volunteers. This is consistent with a conservative selection effect. Taken together, these results tell a consistent story in three parts. First, more conservative individuals are more likely to volunteer for military service. Second, conservatism is tempered by the service, which has a moderating effect. Subsequent analyses indicate that this is driven primarily by social issues, perhaps suggesting that the development of close ties to a broad group of comrades-in-arms instils more socially tolerant attitudes. Third, the socialization effect is not strong enough to override the selection effect—in the end, veterans remain more conservative than their non-veteran counterparts.

The origins and implications of the civil-military gap

Having identified the gap between civilians and veterans, we also consider its origins. Why does the US military tend to attract more conservative individuals to serve in its ranks? While our data do not allow us to answer this question directly, we do speculate on it. We propose that Democrats largely took the blame for the so-called “hollow force” of the late 1970s. This perceived failure to maintain military readiness, alongside the contemporaneous transition to an all-volunteer force, led to the development of a major political cleavage between veterans and non-veterans. This cleavage has only deepened in recent decades, leading to an alignment of military veterans with the Republican Party.

We might also wonder what this polarization portends. Does it matter that veterans have particular political preferences? Not necessarily. And there is no reason to believe that members of the military need to be apolitical. The danger arises in the potential politicization of the institution by civilian leaders. Too much partisan alignment within the armed forces could lead to exploitation by one side or the other for political purposes. While the data do not suggest that the US has reached such a point, the possibility remains. The expansion of recruitment efforts beyond traditional communities and social networks could only help the armed forces to strengthen itself, broaden its base, and insulate it from influence from political exploitation.

- Featured image: “Soldiers help voters beat state deadline” (CC BY 2.0) by @USArmy

This article is based on the paper (with Jonathan Klingler of the University of Mississippi), ‘Would You Like to Know More? Selection, Socialization, and the Political Attitudes of Military Veterans’, in Political Research Quarterly. - Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3tjhxY9