With former President Trump’s announcement this month that he will be seeking another term in the White House in 2024, Zack Scott examines the role of the media in presidential primary elections. He finds that journalists tend to use a set of “newsworthiness values” to determine how to report on candidates, and that those candidates who use angrier rhetoric and provide more biographical information in their speeches – as Trump has previously done – are more likely to get their messages across through the media.

With former President Trump’s announcement this month that he will be seeking another term in the White House in 2024, Zack Scott examines the role of the media in presidential primary elections. He finds that journalists tend to use a set of “newsworthiness values” to determine how to report on candidates, and that those candidates who use angrier rhetoric and provide more biographical information in their speeches – as Trump has previously done – are more likely to get their messages across through the media.

With his November 16 announcement speech, former President Donald Trump became the 2024 Republican presidential primary campaign’s first declared candidate. As candidates announce, they enter a more visible part of the race for the White House, and with that visibility comes the involvement of new actors other than candidates and the parties.

Donald Trump has successfully navigated a Republican primary before. As political scientist Julia Azari has noted, his ability to dominate mass media narratives was crucial to his success. By one estimate, as of March of 2016, Trump had benefitted from nearly $2 billion in free media attention. Most of the voters who will decide the outcome of the series of statewide primaries and caucuses will experience the campaigns only vicariously, with the news media operating as a major conduit. This makes political journalists important gatekeepers and interpreters.

Journalists fulfill this role by relying on a set of “newsworthiness values” that establish professional norms on how to perform the job. A reporter on the campaign trail has a near-infinite array of options on how to create stories. Newsworthiness values serve as shortcuts to help journalists sift through the possible. But, as I argued in recent research, they also serve to reward some candidates over others.

The importance of ‘newsworthiness’ in political campaigns

Two important newsworthiness values are conflict and human interest. All journalists are socialized to think that conflict or the presence of a relatable person at the center are signifiers of news. Political journalists are no different, and so they use these values to decipher the message of the candidate before relaying their interpretation to their audiences.

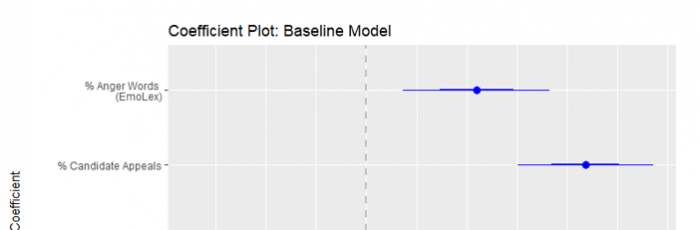

What this means is that candidates who play into newsworthiness values are more likely to get their messages across. For example, as Figure 1 shows, I find that candidates who use angrier rhetoric (which appeal to journalists’ preference for conflict) receive coverage that better represents their message. Likewise, candidates who provide more biographical information in their speeches, a rhetorical cue that should appeal to journalists’ preference for human-interest stories, also have more success at transmitting their message through the media.

Figure 1 – Effectiveness of candidates’ use of anger rhetoric and biographical information

Note: figure plots the standardized coefficient estimates (and 90% and 95% confidence intervals) of the candidate’s anger rhetoric and biographical candidate appeals in models of the amount of agenda message convergence in presidential primary announcement speeches and news media coverage.

Rewarding candidates who are best at appealing to journalists’ newsworthiness values (rather than those who meet other standards more pertinent to the job of being president) is problematic because of a particular authority the media wields in primaries: the ability to elevate certain candidates as focal points.

“Donald Trump” (CC BY-SA 2.0) by Gage Skidmore

Media focal points and coordinating to choose a candidate

The format of American primary contests puts a premium on coordination. Since reforms imposed in the wake of the McGovern-Fraser Commission after the 1968 election cycle, the outcome of the primary process is closely tied to a series of statewide electoral contests. These primaries and caucuses are frequently contested by many candidates, not just two (in 2020, the Democratic Party had at least 27 serious candidates). And the candidates are sufficiently similar that most partisan voters would prefer any of their options over the other party. Such voters want a winner who is broadly appealing more than they want a political soulmate.

Knowing which candidate has the broadest appeal requires knowing what others are looking for. It requires coordination. But voters can’t simply meet to hash things out over a long weekend. When open communication isn’t possible, the next best solution to a coordination problem is fixation on a focal point. Economist Thomas Schelling demonstrated as much with his New York City question. Suppose that you and several strangers needed to all meet in New York City, but you couldn’t talk to each other prior to meeting. Where and when would you show up? Grand Central Terminal at noon tends to be the most common pick, simply because they are particularly well-known places and times for meeting people.

This is the crux of argument from the well-known 2008 book, The Party Decides, as to why party elites are able to get their way (more often than not) in primaries. Party elites can use resources and endorsements to identify focal points for voters, no different than taking out a bunch of billboards saying how scenic Grand Central Terminal is at noontime. But what Trump’s 2016 campaign shows is that focal points can be constructed in other ways. Sometimes, voters might miss the billboards if everyone is holding up and talking about a newspaper article saying that massive crowds are assembling outside Trump Tower. The news media can also be a source of focal points.

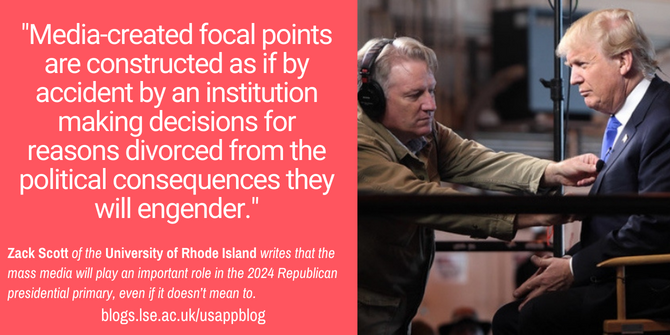

But while party elites are motivated to identify a winning candidate as a focal point (even if they are ultimately incorrect in their judgment), media-created focal points are selected because they are the most skilled at appealing to journalism’s newsworthiness values, not because they are the most capable of uniting the party, winning the general election, or even because they media think they are particularly good candidates. Media-created focal points are constructed as if by accident by an institution making decisions for reasons divorced from the political consequences they will engender.

Looking ahead to 2024

Trump’s announcement speech initiated a series of reflections on how the media could do things differently. But will things truly be different this time around? Perhaps. But the media also responded to a negative ads in 1988 with a temporary prioritization of “adwatches.” The media soon fell back into their familiar negativity bias.

Instead of political journalists being more discerning in how they identify media-created focal points, the more likely change is within the political parties. Trump made himself the media’s focal point in 2016. But the Republican Party struggled to identify its own focal point in turn. Having seen the consequences, perhaps the party has learned not to slip into indecision. Republicans have certainly not shied away from criticizing Trump after the midterms, but saying one candidate should not be the focal point is not the same as uniting behind an alternative. Regardless, presidential primary contests are fundamentally coordination problems, and the media stand as one of the few entities capable of guiding voters to a solution. The media will have a role to play, whether it acknowledges it or not, and that makes the newsworthiness values it uses to fulfill that role of paramount importance.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Courting Coverage: Rhetorical Newsworthiness Cues and Candidate-Media Agenda Convergence in Presidential Primaries’, in Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/3F3oulJ