Many have tended to see the interest of capital and labour regarding automation as deeply opposed. However, Toon Van Overbeke finds reason to believe the interests of employees and employers regarding this type of innovation can be complementary. He shows that economies with institutionalised cooperative bargaining between employers and employees automate at surprisingly higher rates.

Many have tended to see the interest of capital and labour regarding automation as deeply opposed. However, Toon Van Overbeke finds reason to believe the interests of employees and employers regarding this type of innovation can be complementary. He shows that economies with institutionalised cooperative bargaining between employers and employees automate at surprisingly higher rates.

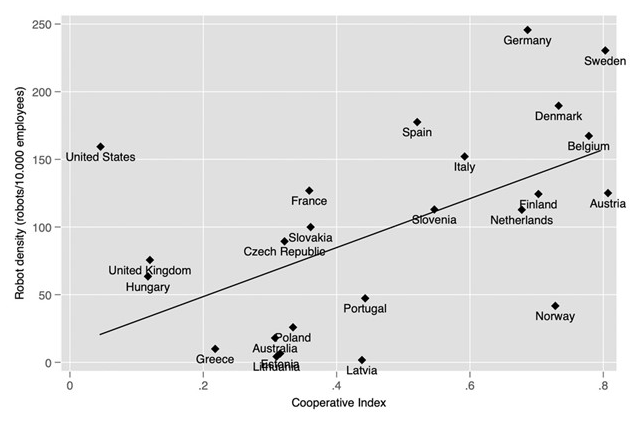

Why do advanced economies automate at such different rates? Could domestic institutions be part of the explanation? And how do these institutions influence the social consequences of that automation? I try to tackle these questions by zooming in on the relation between cooperative institutions and industrial robotisation in 25 OECD countries. Cooperative institutions, such as works councils and sectoral organisations, are institutions in the productive sector that aim to strike a balance between “distribution” and “collective gain” (Hicks and Kenworthy 1998) in capitalist societies by offering venues for institutionalised bargaining between capital and labour (as well as within either category) at different levels of the economy. I show how such institutionalised cooperation between capital and labour is not only associated with more industrial automation but also with more equitable outcomes.

A tool to disorganise workers?

When we look at the distribution of robots across Europe, what is particularly striking is how these similarly advanced economies have adopted this technology at different rates. Places such as Germany, Sweden, and Denmark have relatively high degrees of robot penetration in industry, while other countries such as the United Kingdom only adopt robots at half the rate. How can we make sense of this?

One dominant set of explanations looks at domestic institutions, and particularly the way these institutions set up industrial relations, in order to explain these differences. These existing accounts on automation have tended to see the interest of capital and labour regarding automation as deeply opposed. A first argument proposes more institutionalised labour markets thwart the advance of automation since employees exploit their strong position to hold back the tide of innovation (Leontieff 1982). Automation, after all, reduces the ability of workers to sell their labour on the market. At the same time, another equally zero-sum argument proposes that more deeply institutionalised labour markets actually push automation ahead because they incentivise employers to use labour-saving innovation in order to circumvent labour’s ability to demand high prices (Marglin 1974; Presidente 2020). Automation in this sense is seen as tool to disorganise workers.

However, looking more closely, we find reason to believe the interests of employees and employers regarding this type of innovation can be complementary. On the one hand, employers can profit from bringing employees on board. By guaranteeing buy-in, employers can tap into crucial tacit shop-floor information. At the same time, employers stand to benefit if employees are willing to invest into complementary skills and equally stand to lose if their investments are hit by costly strike action. On the other hand, barring the possibility of fully automatable production, employees also have much to gain from this type of innovation. Productivity growth driven by mass-automation has not only made households across Europe much richer but has also rendered our working lives much safer and far less strenuous. Of course, employees and their unions discount these generational benefits with the potential short-term costs (such as redundancies or underemployment) imposed on workers by these new technologies, unless capital and labour manage to strike mutually beneficial bargains over the distribution of the fruits of innovation.

This is where cooperative institutions come in. I argue that economies with deeply institutionalised cooperative bargaining between employers and employees automate at surprisingly higher rates because cooperative institutions make credible commitments regarding the distribution of costs and benefits of automation between employers and employees possible. Some industrial firms with strong work councils, for example, provide their employees with guarantees that no-one will be made redundant. Anecdotally I have witnessed how this makes employees interested in benefitting from productivity-linked wage rises, keen to share their insights about potential new automation with management. In these firms, employees are also able and willing to retrain and grow alongside new robots, in turn ensuring firms a better return on their investment. The positive effects of cooperative bargaining also materialise at the macro-level. In the Belgian region of Flanders, for example, social partners have actively sought to work together on the issue of automation since both employers and employees stand to gain from internationally competitive firms. This type of social cooperation can generate favourable policies that enable automation to flourish.

To test the merit of this hypothesis vis-à-vis existing explanations, I analysed the effect of cooperative institutions on sectoral robotisation rates in twenty-five OECD economies using a series of panel regressions. The first important conclusion from this analysis is that cooperative institutions are strongly associated with higher levels of industrial robotisation, even when controlling for key confounders.

This, then, raises the question of which mechanisms are exactly driving that automation. Are firms using automation to disorganise workers, like key theories predict, or could these institutions be underpinning a mutually beneficial bargain? To get at this question the analysis also looked at the effect of robotisation on sectoral labour shares and working hours across these different countries. The findings reveal a striking level of divergence between more cooperative economies where robotisation is not fundamentally associated with either a falling labour share of income or working hours at the sectoral level, and more liberal economies like the U.S., where robots seem to drive down the share of the pie going to workers.

So, where does this leave us? First, the account offers a rebuttal to dominant neoclassical as well as (neo)Marxist theories of automation and technology more broadly. Not only should we not expect these processes to play out in the same way across the industrialised world, but this paper provides theoretical and empirical foundations for a more positive-sum interpretation of what might be possible. In doing so, these findings offer a glimmer of hope for debates on the future of capitalist democracy. If capital and labour can indeed manage to strike reasonable bargains, not just over the structure but also the restructuring of production and redistribution, there is some hope new waves of technological change could indeed be to the benefit of the majority. Key stakeholders, however, should not expect positive-sum equilibria to fall like mana from the heavens but realise they are a product of the embeddedness of production within the historical-institutional context of some European countries.

Figure 1 – Robotisation and cooperative institutions in the OECD

Source: Van Overbeke, 2022

- This blog post is based on Conflict or cooperation? Exploring the relationship between cooperative institutions and robotisation, British Journal of Industrial Relations and first appeared at the LSE Business Review blog.

- Featured image by Laurel and Michael Evans on Unsplash

- Please read our comments policy before commenting

- Note: The post gives the views of its authors, not the position USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3X0pVJf