While the United States is considered to be a singular entity, at the beginning of its history most of its people saw the country as a collection of states. In new research, Melissa M. Lee and Nan Zhang examine how 19th century newspapers referred to the United States, finding that by 1900, Americans were more likely to say, “the United States is”, and that this change happened much more slowly in the South. They argue that this difference may be down to radical members of the Republican Party in the North who wished to promote the idea of a strong national government in the wake of the Civil War.

While the United States is considered to be a singular entity, at the beginning of its history most of its people saw the country as a collection of states. In new research, Melissa M. Lee and Nan Zhang examine how 19th century newspapers referred to the United States, finding that by 1900, Americans were more likely to say, “the United States is”, and that this change happened much more slowly in the South. They argue that this difference may be down to radical members of the Republican Party in the North who wished to promote the idea of a strong national government in the wake of the Civil War.

E pluribus unum, a Latin phrase meaning “Out of many, one,” is familiar to anyone who has ever looked closely at American coins and banknotes. First appearing in the Great Seal of the United States in 1782, the phrase refers to the country’s founding, in which the thirteen original colonies joined together to form the new American republic.

The phrase was also aspirational. Despite achieving independence from Britain, the United States was not yet “one” in an institutional sense. Instead, the US Constitution established a system that was “neither wholly national nor wholly federal,” reflecting clashing visions about the nature of sovereign authority. Was sovereignty embedded in the several states or did it reside with the new national government? Put differently, were the United States many, or was the United States one?

How have Americans’ views on sovereignty changed?

What did the citizens of the new country think about the nature of sovereignty? Sovereignty is fundamentally ideational: it rests on the recognition and acceptance of the governed. However, given the absence of scientific polling in the first century of the Republic, how can we study Americans’ views on sovereignty?

In new research with Tilmann Herchenröder of the University of Oxford, we solved this problem by looking at how Americans wrote and spoke about the United States. The intuition is simple: how we speak reveals something about what we think.

We focused on an unusual shift in American English: the transformation of “United States” from a plural noun to a singular noun, for example, from “the United States are” to “the United States is”. We take plural usage as indicating that Americans view the United States as possessing multiple sovereignties embodied in the several states, and singular usage as indicating that Americans view the United States to have a single national sovereignty – a view that comports with how scholars, statesmen, and ordinary Americans alike thought about the meaning.

“E Pluribus Unum” (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) by arbyreed

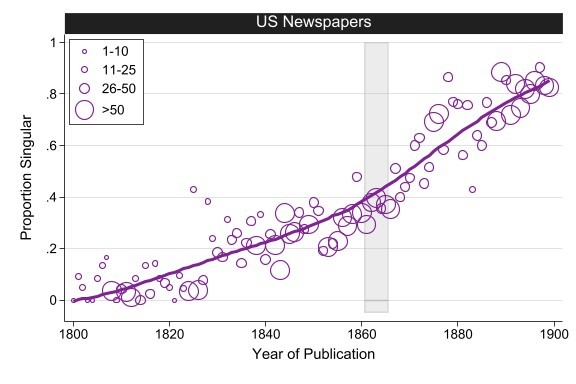

Our data come from US newspapers covering 1800-1899. Figure 1 depicts the relative frequency of singular usage by year. The figure shows a steady increase in singular usage over the course of the century, with a suggestive acceleration in adoption around the time of the US Civil War. Whereas Americans at the start of the century once said, “the United States are,” by the end of the century they were much more likely to say, “the United States is.” We interpret this change to reflect a broader shift in popular thinking of the United States as possessing a single, final sovereignty residing in the national government.

Figure 1 – Singular Usage in US Newspapers

Note: Temporal trends in singular usage in editorials and letters to the editor in US newspapers, fitted using lowess and a 60% bandwidth. Size of the bubbles indicates the number of publications in each year.

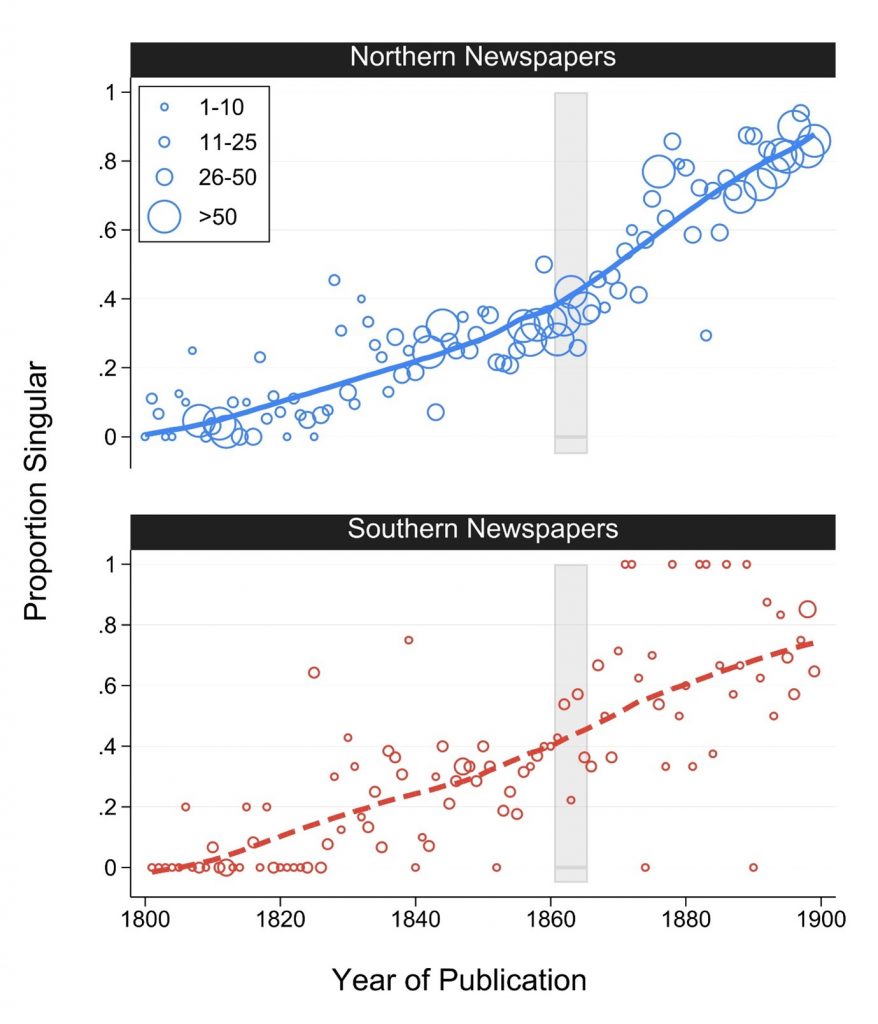

These national-level data obscure fascinating “sectional” (or regional) variation, however. Figure 2 breaks out the trends in based on whether newspapers were headquartered in states that fought for the Union or the Confederacy during the Civil War. A striking pattern emerges when we separate the data this way. The acceleration in singular adoption is limited to the North. The South exhibits no such change in its rate of adoption.

Figure 2 – Singular Usage in Northern and Southern Newspapers

Note: Temporal trends in singular usage in editorials and letters to the editor in Northern and Southern newspapers, fitted using lowess and a 60% bandwidth. Size of the bubbles indicates the number of publications in each year.

The Civil War and the changing view of federal authority

How did this sectional divergence come about? To explain this, we focused on the pivotal role of war and “ideational” entrepreneurs in effecting ideational change.

Wars in the era of mass mobilization entail massive disruptions and demand tremendous sacrifice on the part of citizens. To persuade citizens to bear these costs, leaders must justify why such sacrifices are necessary. These justifications often include appeals to higher principles, such as sovereignty or the safeguarding of democracy. Intellectuals, activists, and leaders thus step into the role of ideational entrepreneurs and take advantage of wartime upheavals to rally support around the ideas to which they are committed.

In the US case, these ideational entrepreneurs were members of the Radical wing of the Republican Party. They believed in a more organic, national conception of sovereignty, and they argued that war was necessary to preserve the existence of the “perpetual Union.” Their views on federal authority were also deeply bound up with the issue of slavery since a powerful national state would serve as the guarantor of equal rights. The South’s secession from the Union provided the Radicals with a critical opportunity to advance their agenda.

By contrast, the South saw no comparable ideational movement. Many historians contend that for Southerners, the Civil War was chiefly about the preservation of slavery, with the theory of states’ rights serving merely as means to this end. Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens himself cited slavery as the cause for secession in his famous Cornerstone Speech.

To explore the role of political entrepreneurs, we turned our attention to speeches made by members of Congress. We compared singular usage before and after the Civil War among Northern Republicans and Northern Democrats. Northern Democrats supported the Union but did not share Radical Republicans’ commitment to a strong national government. As such, we would expect to observe singular usage increase among Republicans but not the Democrats – a pattern that is borne out in the data.

Moreover, we also see similar patterns at the constituency level during the 1864 presidential election. Singular usage accelerated more sharply in Northern counties that supported Abraham Lincoln, the Republican candidate, compared to counties that went for George McClellan, Lincoln’s Democratic opponent.

By creating an unprecedented opportunity for ideational entrepreneurs to act, the Civil War proved to be a critical moment for shaping Americans’ understanding of sovereignty. Our research, however, points to the limits of these persuasive efforts by showing that this transformation took root only among the Northern Republicans. Several more decades would pass before United States truly became “one” in the popular imagination.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘From Pluribus to Unum? The Civil War and Imagined Sovereignty in Nineteenth-Century America’, in American Political Science Review.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/44d9VHG

3 Comments