Scholars often suggest that role models inspire women to run for office, but Amanda Clayton, Diana Z. O’Brien, and Jennifer M. Piscopo argue that exclusion can mobilize women when they are faced with policies which threaten to curtail their rights. Using focus groups and surveys, they find that women’s political ambition increases when women are confronted with the policy consequences of their exclusion from decision-making.

Scholars often suggest that role models inspire women to run for office, but Amanda Clayton, Diana Z. O’Brien, and Jennifer M. Piscopo argue that exclusion can mobilize women when they are faced with policies which threaten to curtail their rights. Using focus groups and surveys, they find that women’s political ambition increases when women are confronted with the policy consequences of their exclusion from decision-making.

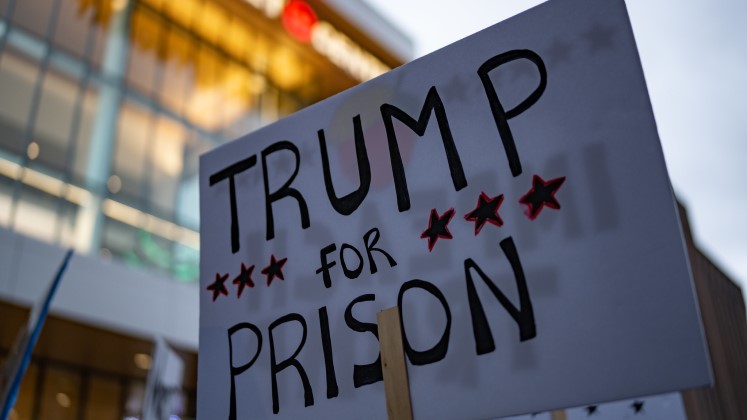

A record number of women ran for the United States Congress following the 2016 election of Donald Trump. An open misogynist, Trump defeated Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton in the Electoral College vote, the first woman to attain a major party’s nomination for the presidency.

Scholars often suggest that role models inspire women to run, but our research began with the fact that the two largest increases in women’s candidacies for the US Congress occurred after events which underscored women’s absence rather than their presence.

In the first “Year of the Woman” in 1992, a then-record number of women ran for Congress following the televised Senate confirmation hearings of Justice Clarence Thomas. A Black law clerk, Anita Hill, accused Thomas of sexual harassment. The all-male, all-white Senate Committee’s interrogation of Hill generated widespread outrage. In the second Year of the Woman, in the 2018 midterms, Trump’s election inspired Democratic women to run, who were motivated to ‘do something’ in response to his victory.

The motivating effects of women’s exclusion

To better understand what motivates women to run for political office, we first conducted focus groups with women who ran or considered running in 2018. Participants centered our attention on the combined effects of the absence of women decision-makers and the risk of women’s rights being rolled back.

In the focus groups, we showed participants the below image from 2017. Then-Vice President Mike Pence is shown meeting with a group of far-right US House legislators (the Freedom Caucus) to discuss repealing federal rules that require health insurance coverage for new and expecting mothers. Our focus group participants expressed outrage seeing this photo and described the importance of “cut-and-pasting” women like themselves into these decision-making situations.

Participants emphasized that seeing all-male groups like the Freedom Caucus make decisions about women’s rights underscored their feeling that “politics is a place where someone like me can make a difference.” Political scientists often describe this feeling by using the term political efficacy.

Exclusion and policy threat work together

Focus groups led us to develop a new theory linking the combination of exclusion and policies which threaten to curtail women’s rights – which we call ‘policy threat’ – to increases in women’s political ambition. We formed a key hypothesis: that exclusion and policy threat will motivate women to seek elected office.

Our focus group respondents had underscored how threat and exclusion need to work together. Respondents reported not feeling motivated when faced with a gender-balanced group, because they thought “women were already there and doing good work,” They also felt demoralized (rather than inspired) when thinking only about exclusion, like Clinton’s defeat.

“Women-s March on DC 106 – Revolution – B” (CC BY 2.0) by Amaury Laporte

An important implication of our theory is that these effects should hold only among women. Of course, women are a diverse group who do not share the same policy preferences. Still, women tend to have stronger preferences for women’s political representation and report feeling more strongly about gender equality issues than men.

Testing ‘women grab back’ with survey experiments

We tested our theory using survey experiments fielded across multiple samples. A survey experiment randomly assigns respondents to read different prompts—also called vignettes—that vary along key dimensions. We varied the gender composition of a hypothetical city council (all-male or gender-balanced) as well as the issue the council will debate in the coming term: women’s reproductive healthcare (the treatment issue) or renewable energy (the control issue). Respondents read one of the four possible vignettes.

Before our respondents read their vignette, we asked about their interest in running for office. After the vignette, we again asked about their interest in running for office (so we could measure changes pre- and post-treatment). We also asked respondents about their interest in running for the city council described in the vignette and looked for behavioral effects by inviting them to click on a link to learn more about running for office.

Women are motivated to run for office when they see men debating their rights

We find that women report increased ambition after reading about an all-male city council poised to legislate on a women’s rights issue. When the council is debating renewable energy, the all-male group does not affect—or even depresses—women’s political ambition.

Figures 1 and 2 show our results. The first one shows the change in respondents’ interest in running for office before and after reading the vignette. Figure 2 shows respondents’ average interest in running for the race described in the vignettes. In both figures, higher values on the y-axis indicate more interest in running, so more political ambition.

The left-hand panels show results for respondents reading about the council poised to legislate on women’s rights. Here, women’s political ambition is higher among respondents who read about an all-male council relative to those who read about a gender-balanced council. By contrast, the right-hand panels show that ambition did not change among respondents reading about the council poised to legislate on renewable energy, no matter whether it was all-male, or gender balanced.

Figure 1 – Change in women’s’ interest in running for office by issue and council gender balance

Figure 2 – Women’s’ interest in running for election by issue and council gender balance

In other analyses, we explored whether increased ambition could be explained by respondents feeling that they could make a difference in politics. Indeed, women reported the most political efficacy after reading about an all-male council debating women’s reproductive healthcare. We also found that men’s political ambition did not change no matter which vignette they read.

Policy threat makes exclusion relevant for women

Together, our results demonstrate that exclusion combined with gendered policy threat raises women’s political ambition, particularly among those who believe that they can make a difference. Our study reproduced the real-world effect of the US “Years of the Women.”

Our research underscores that political ambition is both flexible and context dependent. And rather than focusing on how women’s presence or absence alone motivates women, we look at policy threat in combination with women’s numbers. We find that policy threat makes exclusion important and relevant, inspiring some women to seek a seat at the table.

- The data and replication code for this research is available, here.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Women Grab Back: Exclusion, Policy Threat, and Women’s Political Ambition’ in American Political Science Review

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3O7f92b