The pandemic temporarily paused the rising trend of social unrest seen until 2019. Yet there is a growing risk of social discontent translating into social unrest. Metodij Hadzi-Vaskov, Samuel Pienknagura and Luca Antonio Ricci write that social unrest can have a sizeable impact on the economy—a one percentage point reduction in GDP six quarters after. However, these effects can be mitigated by strong institutions and a country’s policy space.

The pandemic temporarily paused the rising trend of social unrest seen until 2019. Yet there is a growing risk of social discontent translating into social unrest. Metodij Hadzi-Vaskov, Samuel Pienknagura and Luca Antonio Ricci write that social unrest can have a sizeable impact on the economy—a one percentage point reduction in GDP six quarters after. However, these effects can be mitigated by strong institutions and a country’s policy space.

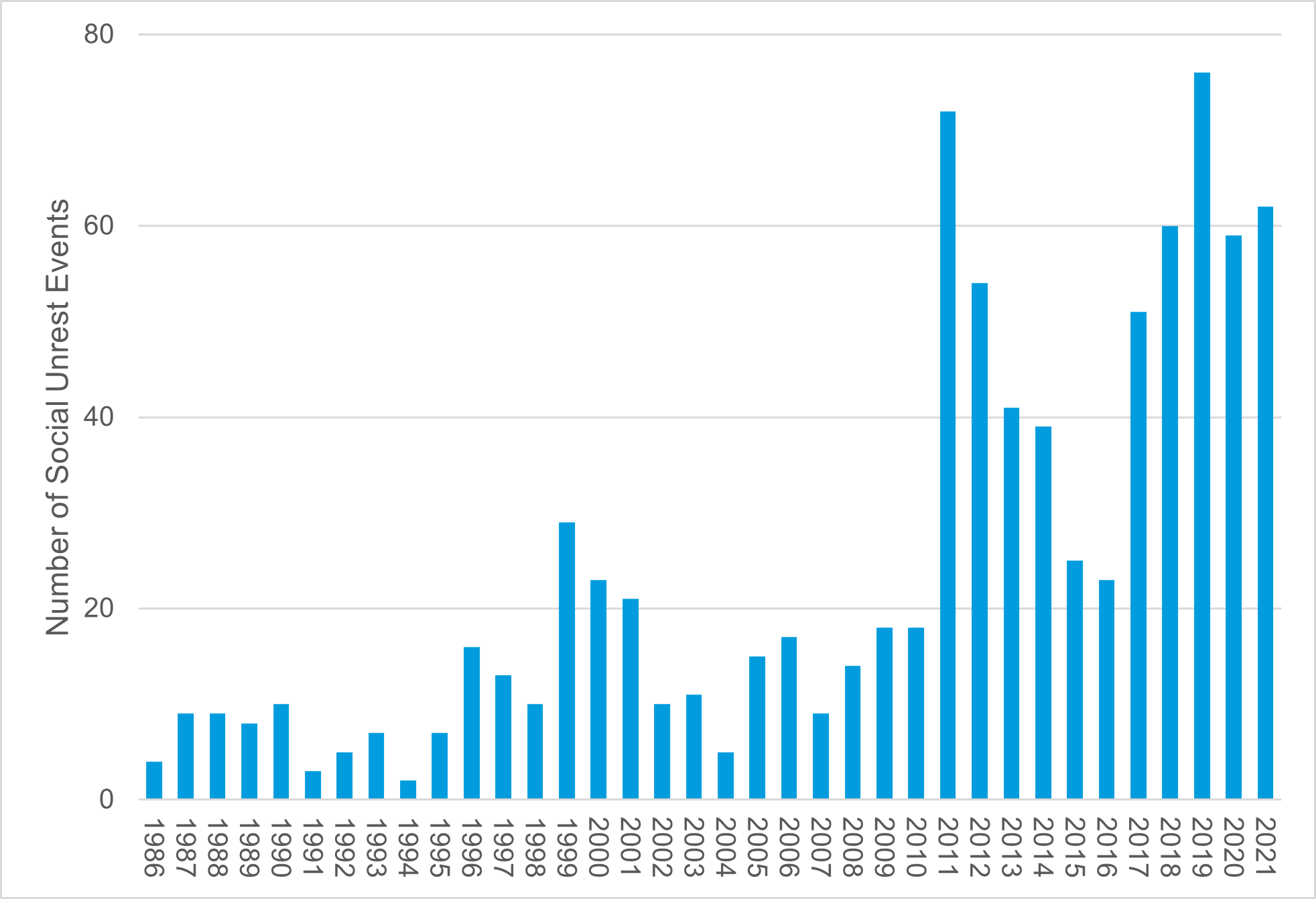

Social unrest affected both emerging market economies (such as Chile and Lebanon) and advanced economies (such as France and Hong Kong) in all corners of the world. Equally varied were the triggers of these events—new taxes, utility fee hikes, subsidy cuts, legislative changes, electoral discontent, and so on. All this led to 2019 being coined “the year of street protest”. And that year was not an exception, given that many cases were visible in the last decade, as documented in a dataset recently assembled by Barrett et al. (2022).

Figure 1 – Social unrest events peaked in 2019

Source: Hadzi-Vaskov, Pienknagura and Ricci (forthcoming) based on dataset assembled by Barrett et al. (2022).

Pressure might be building up

The strict lockdown measures of the early months of the pandemic, together with fears of contagion, dimmed people’s willingness to gather in big crowds and led to a decline in the frequency of unrest episodes in 2020, which has only slightly risen in 2021 (Barrett, 2022).

But as the economic impact of the pandemic is compounded by the global effects of the war in Ukraine, concerns about social discontent and potential new bouts of social unrest are rising (The Economist, 2022). Indeed, the burden of the pandemic has fallen disproportionately on vulnerable groups and has exposed societal disparities (IMF, 2020). And these are the ingredients that in the past have led to social unrest in the pandemic aftermaths (see Barrett and Chen, 2021; and Saadi Sedik and Xu, 2021). In addition, inflation—especially pushed by the higher energy and food prices—has reached the highest levels in decades (IMF, 2022a). This raises concerns about potential pickup in unrest, as price jumps—especially of food and fuel—are found to be consistent predictors of social turmoil (Redl and Hlatshwayo, 2021).

If such developments spark another series of social discontent or unrest, what might be the impact of such unrest episodes on economic performance?

Renewed unrest could affect economic recovery

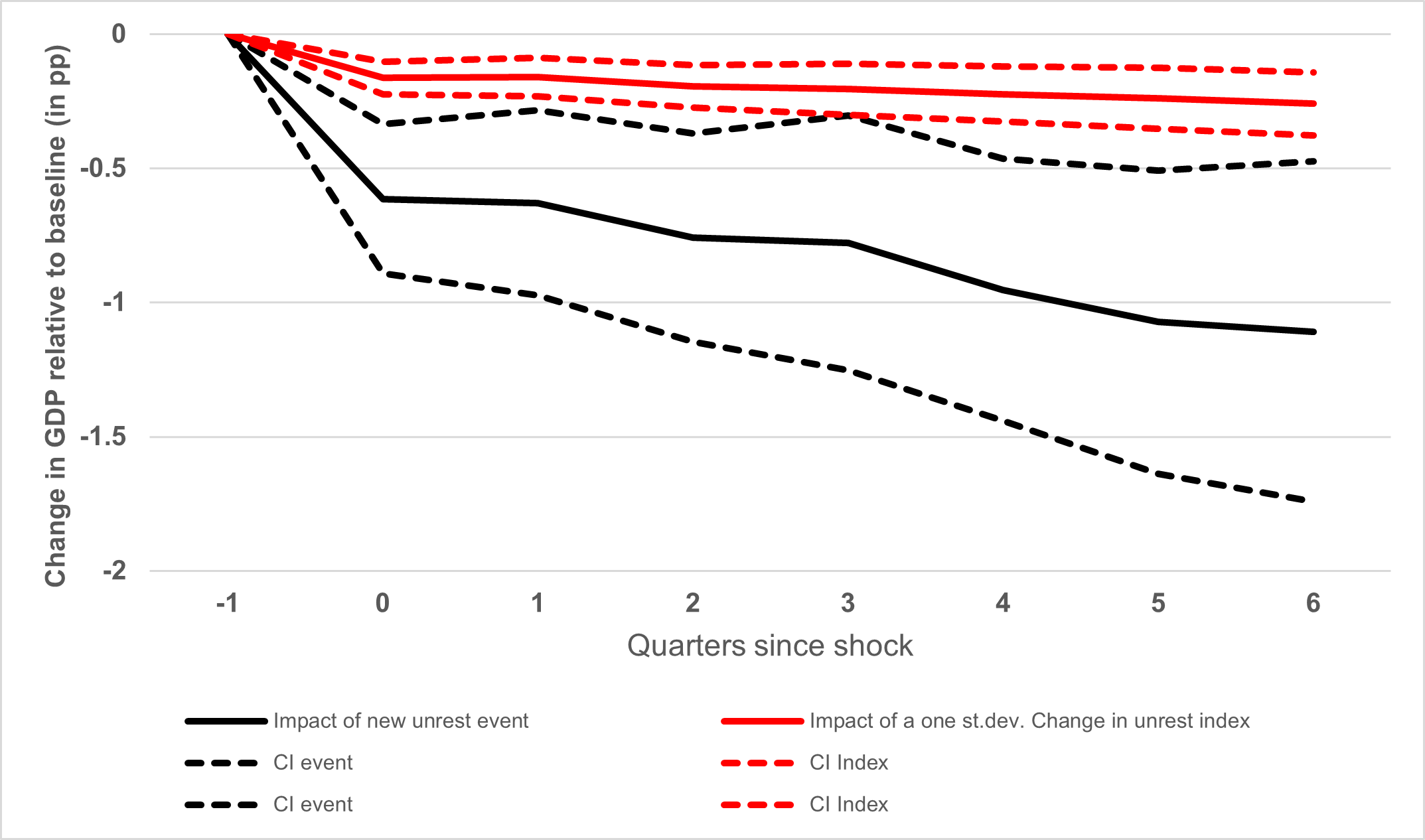

The prospects of new episodes of social unrest cast a shadow on the economic outlook. In Hadzi-Vaskov, Pienknagura and Ricci (forthcoming), we estimate that the macroeconomic impact of social unrest episodes can be large: on average, a one standard deviation increase in the social unrest index computed by Barrett et al. (2022) results in a reduction of over 0.2 percentage points in GDP after six months from the shock, relative to similar countries that do not experience unrest. This is driven by contractions in manufacturing and services (sectoral dimension), and consumption (demand dimension). Countries that are hit by a “new unrest event”—where unrest events are defined by Barrett et al. (2022) as a large increase in the unrest index—see an even larger lasting reduction in GDP (about 1 percentage point after six quarters).

For comparison, the average impact of social unrest events that we estimate in our paper is comparable to the impact on oil exporters’ GDP of an oil price plunge (defined as a decline by 30 per cent or more over a six-month period) combined with a recession (World Bank, 2020). It is also comparable to the impact of a fiscal consolidation of around 1 per cent of GDP (Carrière-Swallow, David, and Leigh, 2021).

Figure 2 – Social unrest has a lasting adverse impact on GDP

Source: Hadzi-Vaskov, Pienknagura and Ricci (forthcoming). Note: A “new” unrest event is defined as an unrest event (as defined by Barret et al. 2022) that follows eight quarters of no unrest events.

Not all countries are equally exposed

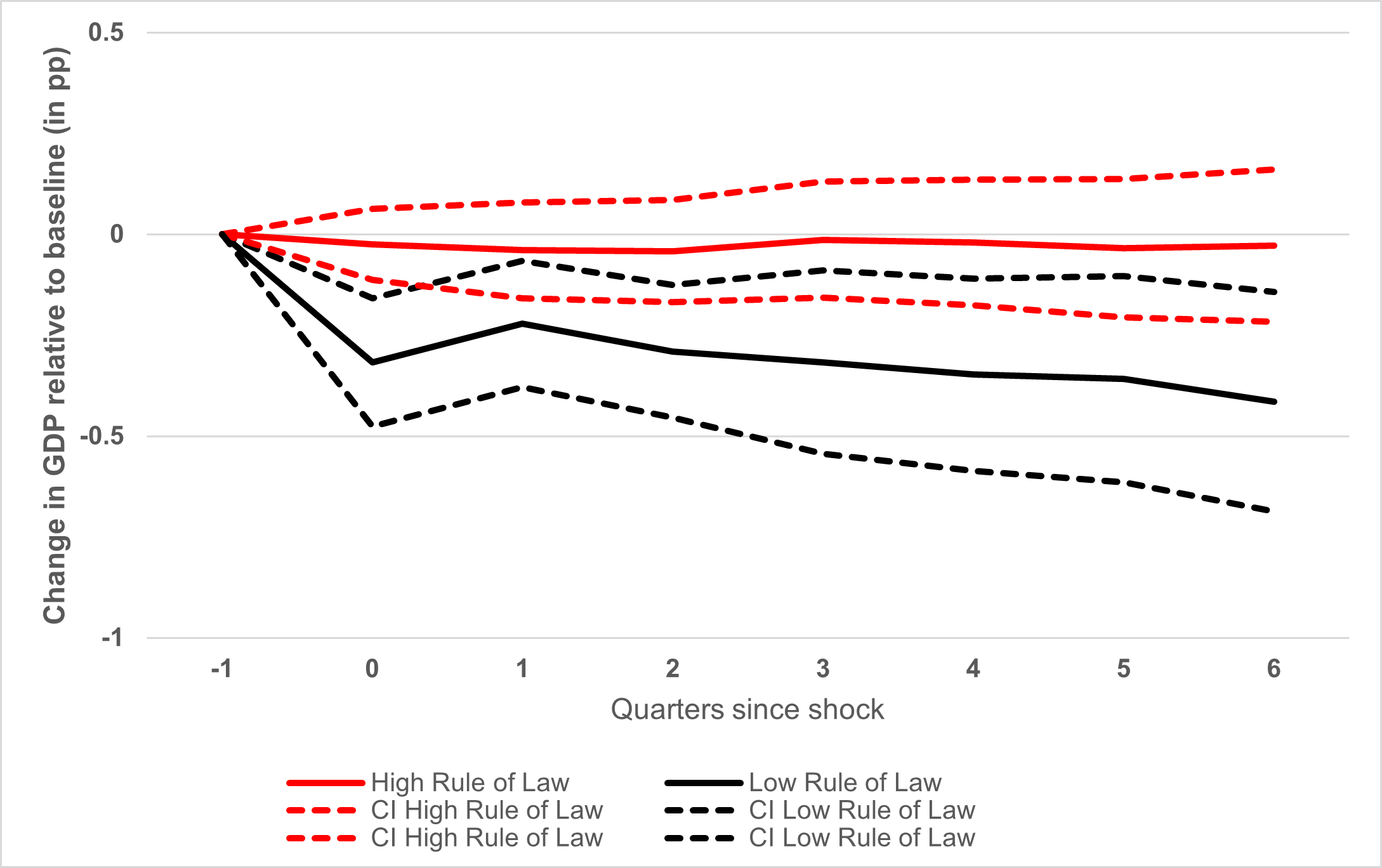

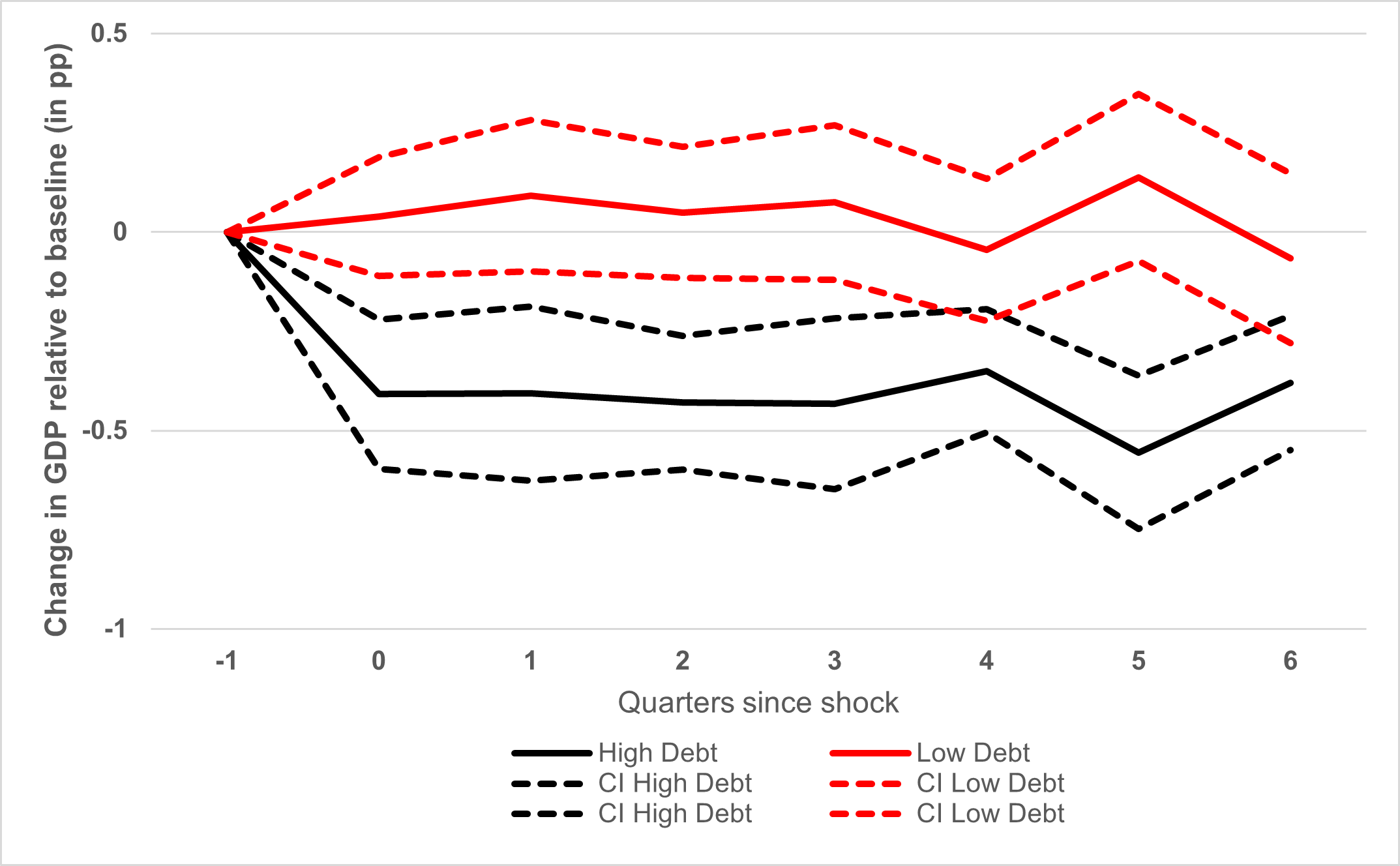

The adverse impact of unrest is typically larger in countries with weak institutions and with low policy space. Thus, countries that started the pandemic with weak fundamentals are likely to suffer the most, should social discontent translate into unrest.

Figure 3 – Countries with weak fundamentals suffer larger economic impacts

A. By Rule of Law

B. By Debt Level

B. By Debt Level

Source: Hadzi-Vaskov, Pienknagura, and Ricci (forthcoming).

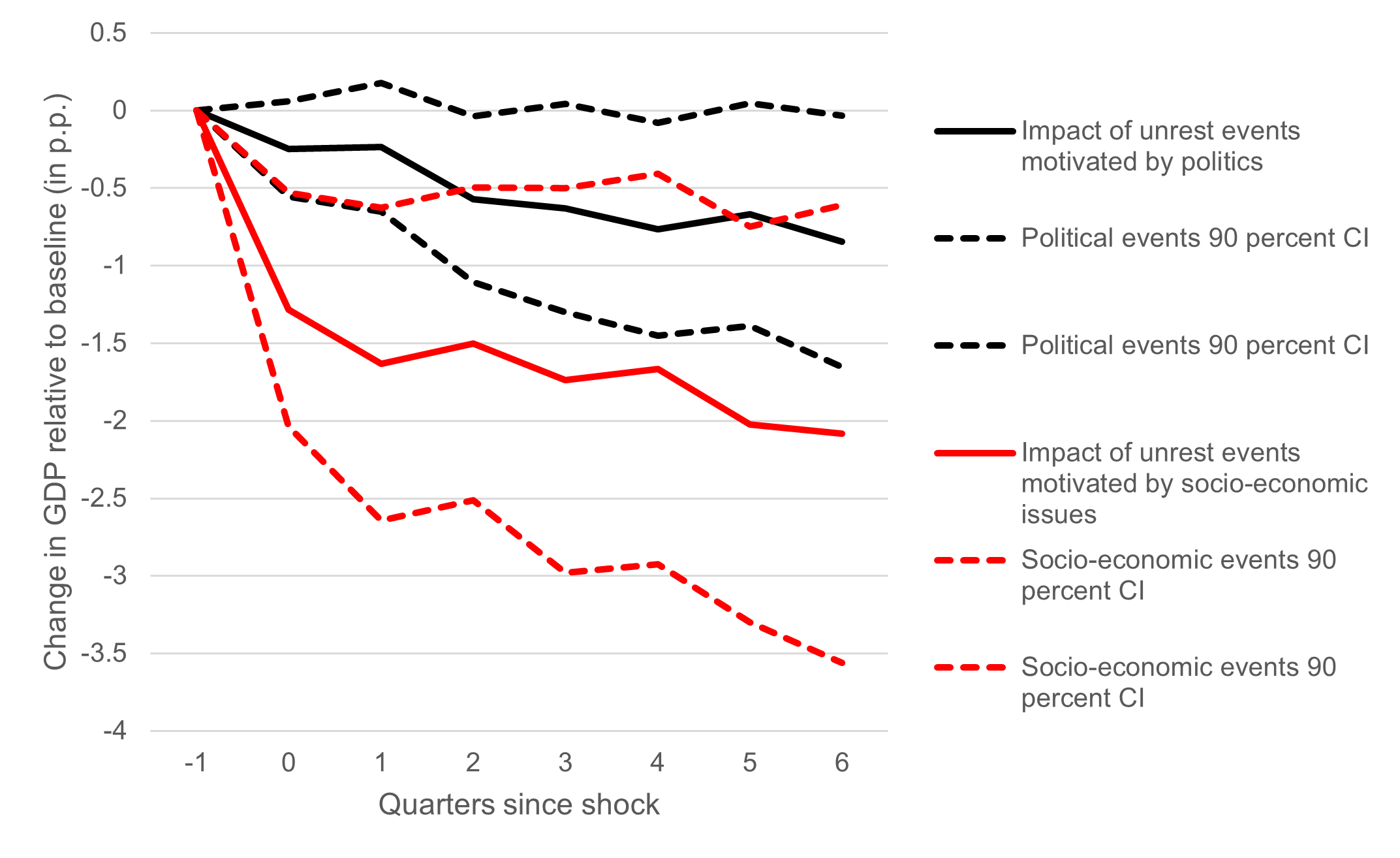

When considering different types of unrest events, protests motivated by socio-economic concerns usually result in sharper GDP contractions with respect to those associated mainly with politics/elections. And the combination of both socio-economic and political factors have the biggest impact.

Figure 4 – Unrest motivated by socio-economic issues have a larger impact on activity

Source: Hadzi-Vaskov, Pienknagura, and Ricci (forthcoming)

Against this backdrop, the ongoing commodity price surge, and its broader socio-economic implications, deserve close monitoring and policy vigilance. Countries that are unable to cushion the surge in food prices, particularly those in Africa, may be hit the hardest (IMF, 2022b, and Vanek and Goko, 2022).

Seeking social consensus to design adequate policies

Public protests can be an important expression of the need to change policy. Understanding and anticipating people’s concerns and needs remains a difficult task but is a challenge that today needs to be tackled urgently. Mitigating the impact of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine is crucial. As in the 2020-22 period, this would require protecting people from the worst consequences of these shocks, by cushioning the impact of inflation, supporting employment, containing the long-term economic impact of the sequence of shocks of the last two years, and more generally protecting the most vulnerable and those who have been left behind. As before, it remains crucial that chosen policies are implemented in a timely, targeted, and temporary fashion, particularly given the more limited fiscal space and heightened public finance risks (IMF, 2022c). To ensure success and avoid strife, Cárdenas et al. (2021) suggest that adequate reforms can be achieved only through a broad social dialogue on the role of the state and on how to sustainably finance budget pressures. Otherwise, the economic costs of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine will likely be compounded by the costs of the ensuing unrest.

- This blog post is based on The Macroeconomic Impact of Social Unrest, forthcoming in the B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics and first appeared at LSE Business Review.

- Featured image by Oscar Brouchot on Unsplash

- Please read our comments policy before commenting

- Note: The post gives the views of its authors, not the position USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3MFiowB