Many US cities, facing revenue shortfalls, try to supplement their incomes through fines such as ticketing drivers at traffic stops. In new research, Siân Mughan and Akheil Singla examine the role of the criminal justice system in revenue-motivated policing. They find that judges in cities which need revenue are more likely to suspend licenses more quickly, and that police are more likely to issue more tickets, but only when the city government retains the revenue from those tickets. They argue that denying or limiting local government access to revenue raised by ticketing could curb revenue-motivated policing.

Many US cities, facing revenue shortfalls, try to supplement their incomes through fines such as ticketing drivers at traffic stops. In new research, Siân Mughan and Akheil Singla examine the role of the criminal justice system in revenue-motivated policing. They find that judges in cities which need revenue are more likely to suspend licenses more quickly, and that police are more likely to issue more tickets, but only when the city government retains the revenue from those tickets. They argue that denying or limiting local government access to revenue raised by ticketing could curb revenue-motivated policing.

“Ferguson’s law enforcement practices are shaped by the City’s focus on revenue rather than by public safety needs.” That was one of the startling conclusions of the United States Department of Justice’s investigation into the Ferguson Police Department following the fatal shooting of Michael Brown by a Ferguson officer in 2014.

At the time, it was not clear whether Ferguson was an outlier or whether the practice was common. But in the years since the report, it has become clear that Ferguson was neither the first nor the only local government to pursue revenues through its criminal justice system. The phenomena is so common it has numerous monikers: ‘policing for profit’ and ‘revenue motivated policing’ among them.

A common finding of research on revenue-motivated policing is that fiscal stress – when expenditures are consistently greater than revenues — motivates local governments to generate revenues through their law enforcement agencies. The story goes that these monies can patch holes in local government budgets without levying additional taxes.

The contours of the narrative are more-or-less settled. But the details of how specifically these practices happen are unclear. For instance: how do police officers change their behavior in response to fiscal stress? The Ferguson police department targeted the city’s Black residents. Other evidence shows that in response to fiscal stress police issue tickets to drivers who may be more likely to pay the fines: wealthier, white drivers.

Moreover, police officers do not actually collect the money from the tickets they issue. That requires a court. What role does that part of the judicial system play? In Ferguson’s case, the city’s court was an active participant. Not only was the court responsible for collecting the financial penalties associated with tickets, it also aggressively applied discretionary fees (e.g., late fees), declined to consider a defendant’s ability to pay, and structured its operating hours to confuse defendants and force them to incur additional financial penalties as a result.

Understanding Factors Driving Revenue Motivated Policing

In new research we examine the details of revenue-motivated policing across the criminal justice system. Our goal is to iron out the specifics of what is happening. So, we focus on clearly defining and measuring two critical concepts: revenue need and revenue retention.

Other work on the subject typically examines fiscal stress based on changes in revenues from year to year. Such measures may capture revenue shortfalls. However, they may also reflect the preferences of local voters and officials. For instance, a mayor can reduce tax revenues because the residents want to pay less taxes. In this case a decline in revenues is not indicative of fiscal stress. To address this, we use a novel feature of Indiana’s property tax system. There, cities are only told of the total amount of property tax revenue they can collect after they have finished their budgetary processes. Often the amount they can collect is less than they budgeted for. We refer to these losses as revenue need. This is an unusually strong measure because it captures unplanned revenue shortages. In other words, it does not reflect what locals want.

“Cleveland police stop” (CC BY-SA 2.0) by Tim Evanson

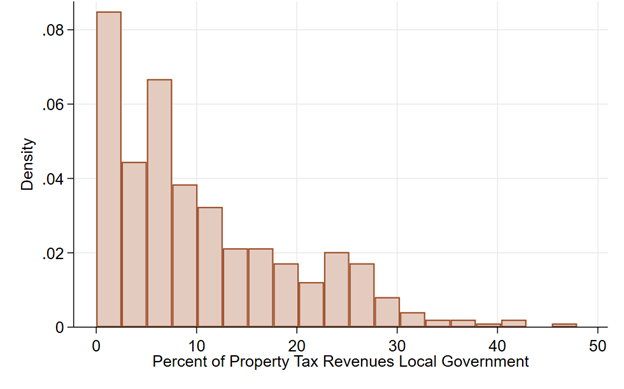

As seen in Figure 1, some local governments are essentially unaffected while others are unable to collect a significant portion of their planned revenues – up to 48 percent!

Figure 1 – Property tax revenues lost as a percentage of total property tax revenues

Our second concept is a critical and often overlooked issue: revenue retention. We simply ask whether local governments can keep ticketing revenues. Usually, law enforcement agencies do not directly retain the money generated by the tickets they issue. This avoids negative incentives that might lead to over-ticketing. But the local government overseeing the police department does not necessarily keep these monies either. They are often distributed to county and/or state governments. The incentives to ticket are notably very different depending on revenue retention. There is no reason to think revenue need would lead to revenue-motivated policing if the city’s ability to profit from them is absent.

In our work, revenue retention is dictated by the presence of a municipal (local) court – courts that are established and funded by the city rather than the state government. If a city has a court, it retains a large fraction of the revenues from tickets filed in that court. In the absence of such a court, the monies are shared between county and state governments.

Measuring the role of revenue need and revenue retention in revenue-motivated policing using traffic ticket data

We use traffic ticket data from Indiana to examine the relationship between revenue need, revenue retention and revenue-motivated policing. A feature of our study is that our data comes from the court system rather than police departments. As such, we have some unique information; we can see if a judge suspends a driver’s license when a driver fails to pay their ticket, a common policy that is intended to induce payment.

Our analysis reveals that revenue need induces police to issue more tickets, but only when the city government retains the revenue from those tickets. And in cities with revenue retention, increased revenue need results in increased ticketing of white drivers. There is no change in the number of tickets issued to Black drivers.

We also find that as revenue need increases, driver income increases. In addition, people receiving tickets when revenue need increases are also more likely to pay the fines from the ticket. This suggests that revenue need leads police to issue tickets to wealthier drivers. These effects are the strongest among white drivers, providing further evidence that fiscal stress leads to an increased ticketing of white drivers.

Revenue needs leads judges to suspend licenses more quickly

We also extend our inquiry into the court system. We looked at whether judges in cities with increased revenue need use their authority to generate more revenue. To study this we count the number of days a judge waits before suspending a drivers’ license. We find that revenue need leads judges to suspend licenses more quickly; when revenue need increases by one percent, judges wait three fewer days before suspending a license. This means judges appear to be revenue motivated as well.

Our findings offer important guidance to policy makers and advocates interested in these issues. Our most consistent and convincing finding is that that revenue retention is critical. Denying or limiting local government access to ticketing proceeds is a promising approach to curbing revenue-motivated policing. It may also help reduce perverse revenue incentives in judicial suspensions of drivers’ licenses for failure to pay.

It is also important to understand what policy changes will not accomplish. By compelling increased ticketing of white drivers, revenue motivated policing reduces racial disparities in traffic outcomes. The obvious implication is that curbing this practice may not improve racial disparities in traffic outcomes.

- This article is based on the paper, “Does revenue-motivated policing alter who receives traffic citations? Evidence from driver race and income in Indiana”, in Public Administration Review.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/43GCpsS