Last year the Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) which provides billions in subsidies and tax credits to US companies. Drawing on her book, Spending to Win, Stephanie Rickard writes that the IRA shows how many governments have turned to subsides or increased spending on them to not only bolster their own industries, but often more importantly, to win voters’ support.

Last year the Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) which provides billions in subsidies and tax credits to US companies. Drawing on her book, Spending to Win, Stephanie Rickard writes that the IRA shows how many governments have turned to subsides or increased spending on them to not only bolster their own industries, but often more importantly, to win voters’ support.

Many governments are increasingly providing subsidies to domestic producers. The most prominent example is United States’ Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which provides $369 billion in green subsidies and tax credits.

While striking, the rise of subsidies was foreseeable. In my 2018 book “Spending to Win”, I predicted that subsidies would increase in the coming years. Several observations led me to this conclusion. First, governments needed alternative policy tools, like subsidies, to protect domestic producers, as more and more international agreements restricted tariffs. The Japanese government, for example, planned to increase subsidies to pig farmers to compensate for the reduction in pork tariffs established as part of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) multilateral trade agreement, now the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Second, China’s subsidies, particularly those to its steel industry, were already prompting demands for government assistance in other steel-producing countries including France, the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Third, some EU Member States were pressing for, and winning, relaxations of State Aid rules. France and the UK lobbied for exemptions for subsidies for film making. Just months after the French government threatened to veto the bloc’s trade talks with the United States, the European Commission published new rules making it easier for governments to subsidize moviemaking.

Big increases in subsidies to win voters’ favor.

In short, a rise in subsidy spending was foreseeable given the currents emerging in the global economy. However, in 2018, I had no idea just how much subsidy spending would rise. Among G7 countries, subsidy spending grew by 233 percent from 2016 to 2020 according to The Economist. Part of this increase was due to COVID-19. But spending on subsidies remains well above pre-covid levels.

The reasons behind subsidies are varied, but one outstanding motivation is clear: politics. Governments use subsidies to win votes, hence my book’s title “Spending to Win”. Of course, subsidies may also achieve other goals: increasing production capacity, attracting foreign investment, solving a market failure. Yet virtually all subsidies are provided, at least in part, for political reasons.

Incumbent governments and politicians supply subsidies in an attempt to increase their support among the electorate (or selectorate in non-democracies). Their efforts vary across countries in response to electoral incentives. The pressure to supply subsidies is greatest in countries with plurality electoral rules and geographically concentrated economic activities. In such instances, elected incumbents gain substantial political benefits from providing subsidies. In contrast, the incentives to supply subsidies are lowest in countries with closed-list proportional electoral rules and geographically concentrated economic activities. In these cases, incumbents gain little at election time from supplying subsidies.

These political dynamics help to explain why some countries frequently provide generous subsidies while others largely stay out of the subsidy game. France, for example, typically spends three to four times as much on subsidies as Italy.

Varied enthusiasm for subsidies

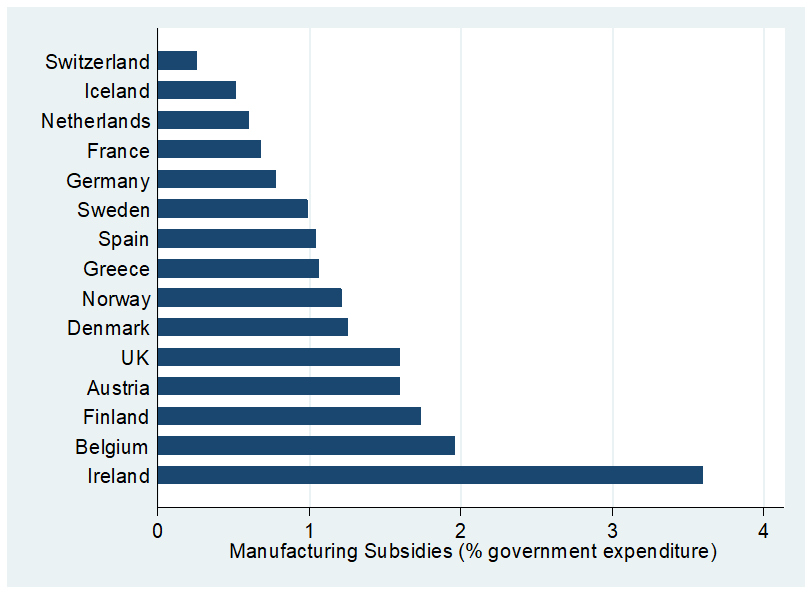

Even in the wake of the 2008 global economic crisis, governments’ enthusiasm for subsidies varied, as Figure 1 illustrates. Some leaders raced to provide aid to troubled industries. The French president unveiled a “strategic national investment fund” to buy stakes in certain French industries to protect them against foreign “predators.” The Australian government increased budgetary assistance to industry by 26 percent from 2006 to 2010 and the UK government poured money into select parts of the economy that were deemed to “make a difference.”

Figure 1 – Variation in industrial subsidies

Source: Spending to Win (Cambridge University Press, 2018)

But not all governments were equally keen. In Sweden, the government refused to bail out the ailing automotive industry following the 2008 global financial crisis. The Prime Minister said he would not put “taxpayer money intended for healthcare or education into owning car companies”. The German government similarly resisted demands for industrial subsides. Defending this decision, the German Minister for Economics and Technology said that privileging certain industries went against “all successful principles of our economic policy.”

Such variation suggests how the looming subsidy war, sparked by the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), may play out. Not all governments will be equally willing (or able) to provide subsidies to domestic producers. Countries with fewer domestic incentives to provide subsidies may be well placed to lead international efforts to stop a full-blown subsidy war before it spirals out of control.

- Featured image credit: “P20220816CS-0389” by The White House is United States government work.

- This article is based on the book Spending to Win (Cambridge University Press, 2018)

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/46lyPGf