The recent crisis over the debt ceiling has resurfaced fears that US debt mismanagement puts a question mark to claims of insurmountable US hegemony. Now that the treasury has lifted its cap on issuing sovereign debt for the next two years, it should consider issuing future debt with a 100-year bond, writes Gordon Alexander Schlicht.

The recent crisis over the debt ceiling has resurfaced fears that US debt mismanagement puts a question mark to claims of insurmountable US hegemony. Now that the treasury has lifted its cap on issuing sovereign debt for the next two years, it should consider issuing future debt with a 100-year bond, writes Gordon Alexander Schlicht.

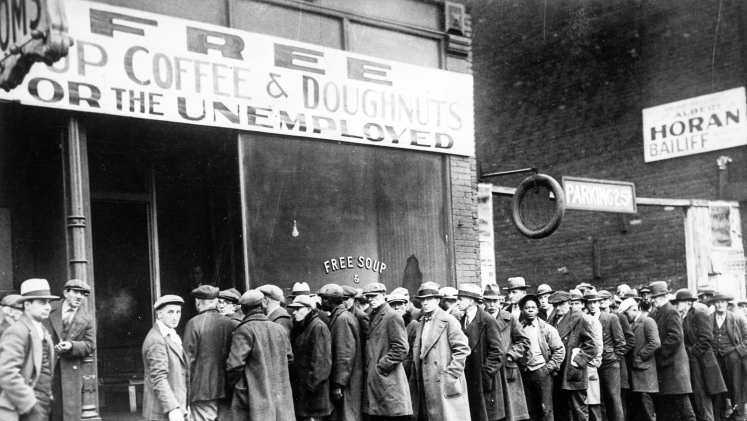

A spectre is haunting America—the spectre of its growing federal debt. Earlier this month, an eleventh-hour deal was reached between the Democrats and Republicans to raise the debt limit and subsequently signed into law by President Biden. On June 3, 2023, the US government once again avoided economic disaster amid alarm of a potential credit downgrade.

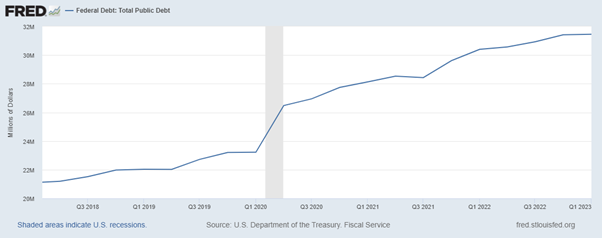

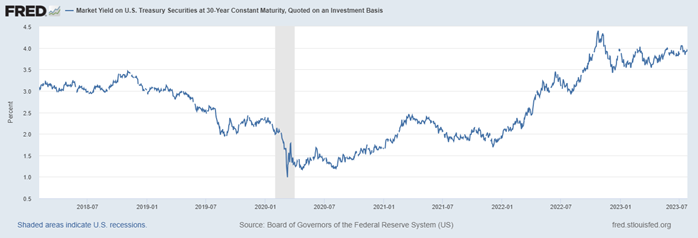

While the debt limit crisis had been looming for months, sovereign borrowings were nearing their $31.4 trillion limit (Figure 1). The Treasury had been unable to issue incremental debt—if the boundary had not been raised, the government could not have paid its bills. A credit downgrade, or ultimately, default on US debt would have an irreversible effect on global risk premia, frontier economies’ credit spreads, and the very notion of American trade, currency, and security hegemony.

Figure 1 – Outstanding US public borrowing 2018-23

Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury. Fiscal Service

The recent deal was a relief to market participants; however, it also cast a light on structural weaknesses in US fiscal policymaking. Short-term policy rotation is a necessity of strong democracy, but it’s not ideal for market confidence in bonds. Debt ceiling anxiety serves a periodic reminder of the need for congress to resolve the fiscal challenges of a now over $32 trillion national debt that stretch beyond a term in office, a generation, or several lifetimes.

On the positive side, the government is now able to issue debt and restore a functional treasury curve until 2025. Therein lies an opportunity for innovation. A new, ultra-long debt instrument, in the form of a 100-year bond, could allow United States government to bolster financial stability, capitalise on favourable interest rates, and optimise capital allocation.

Longer-term bonds in Europe and elsewhere

Historically, the most popular maturity for ultra-long bonds was 50 years, interspersed with episodes of substantial demand for 30-year and 100-year bonds – first sighted in the Eurozone during 2016 and 2021. Reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic, Germany’s state of North Rhine Westphalia raised two billion euros by selling a 100-year bond; France swiftly followed with the announcement of its first 50-year bond. Mexico, Indonesia, and Austria, as well as corporates such as Disney and Coca-Cola also maintain 100-year bonds.

According to the Bank for International Settlements, which represents many central banks, governments then issued $240 billion worth of ultra-long bonds globally through Q3’22, on a net basis. Meanwhile, the average maturity of sovereign bonds grew by about 20 percent. As of April 30, 2023, the FTSE World Government Bond Index (WGBI) had an average duration of 7.62 years, as compared to 6.60 years a decade ago. It peaked at 8.75 years in Q1’2022.

These trends were propelled by a number of factors, including low interest rates, which made it cheaper for governments to borrow money; inflation, which made foreign investors more willing to accept lower yields on longer-dated bonds;COVID-19-related budget deficits which prompted governments to spread borrowing over a longer period making debt management easier; the rise of emerging market issuers; and the growth of the green bond market, especially in the European Union.

JHerbstman, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The case for longer-term bonds in the US

While the decision to issue 100-year bonds requires careful consideration and risk assessment, empirical evidence supports the potential economic advantages and financial stability that can be achieved. Bar its periodic debt ceiling debates, the US economy is an emblem of long-term stability. It may be one of the very few countries capable of issuing ultra-long bonds with sufficient demand to price them at a near zero interest rate – even in a higher-yield environment than the prior decade. To reap long-term benefits the US government can follow the Eurozone’s example.

Protecting against interest rate fluctuations and locking in budget certainty

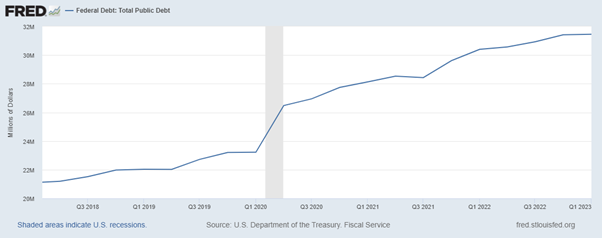

The current interest rate environment provides an advantageous backdrop for the US government to issue 100-year bonds. While no longer historically low, yields on long-term US Treasury bonds make it an opportune time to lock in financing at favourable rates. Trends in the stability of the world order, de-globalisation and an inflation regime above the Fed’s two percent target may mean that interest rates have already levelised for the foreseeable future. Today, the yield on the 30-year Treasury bond is around 3.89 percent (Figure 2), which serves as a theoretical minimum for America’s long-dated cost of borrowing.

Figure 2 – Market Yield on U.S. Treasury Securities at 30-Year Constant Maturity

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

In this context a centurial bond would shield the government from forward interest rate fluctuations and provide long-term budget certainty, mitigating the risk of higher debt servicing costs in the future. By issuing an attractive long-duration instrument, the US government lowers the probability of short-run default, and in turn, promotes an increase in credibility and a reduction in rates, which at the same time lowers refinancing and repayment risk.

When US interest rates were near-zero, as was the case from 2008 to 2015, the Treasury could have priced a negative interest rate on a 100-year bond, effectively charging developing countries – and risk-hedging investors in developed markets – for a protective mechanism against currency volatility. If the market still buys into the notion of negative real yields during a “flight to safety,” the yield of a 100-year bond in a recessive environment later this year is in the realm of one to three per cent – still a substantial discount to current short-run rates.

Reducing refinancing risks and enhancing stability

By diversifying the Treasury’s debt profile with 100-year bonds, the US government can extend the average maturity of its outstanding debt, reducing the need for frequent refinancing. This approach contributes to financial stability by minimising the risks associated with short-term interest rate uncertainty. The trailing five years’ average maturity of outstanding US Treasury debt was 69.6 months (Figure 3). By extending the maturity to one hundred years, the government can smooth out debt repayment obligations and reduce rollover risks, thereby strengthening its fiscal position and instilling greater confidence in investors.

Figure 3 – US Treasury Securities Maturing in over 10 years

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US)

Attracting long-term investors

100-year bonds can attract a diverse range of investors, including pension funds, insurance companies, and sovereign wealth funds. Such institutions are well capitalised and maintain a longer-term investment horizon, making them well-suited to participate in the 100-year bond market, because they are not particularly concerned about duration risk. Their liabilities tend to be greater than 30 years (e.g., lifetime insurance policies or retirement payouts at the end of a career). They should be able to match the promise they have made to customers with a similar-maturity bond and reduce their investment risk – but are currently unable to do so with the existing treasury bonds.

Would there be market appetite for the 100-year bond? Bankers like to evaluate new instruments by their precedents. The closest comparable issuance in this instance is Austria’s AA+ zero-coupon 100-year maturity. Its 2020 special issuance was oversubscribed by nearly nine times.

Facilitating long-term planning, strategic investments, and economic stability

Issuing 100-year bonds allows the US government to strategically allocate capital towards long-term projects and national priorities. Infrastructure investments, research and development initiatives, and sustainable energy projects often require extended time horizons to generate substantial returns. It also forces policymakers to stipulate spending around long-term committed financing, rather than vice versa.

In addition, long-term bonds may have potential economic benefits. A 2015 study found that longer-maturity debt is broadly associated with higher economic growth, as it provides stability, supports investment, and reduces financing constraints. Moreover, the participation of long-term investors enhances market liquidity by way of investor diversity and reinforces the US economy’s resilience.

Intergenerational equity

The 100-year bond allows governments to spread out their borrowing over a longer period, which makes it easier to manage debt levels and ensures a generational wealth transfer without disproportionate burden. When current generations pay for capital improvements upfront, they are the only ones who contribute to the cost, while the policies and infrastructure they fund benefits future citizens. Economic science cannot quantify the state of fairness or unfairness in our current sovereign bond market arrangement — fairness and justice are subjective concepts, and there is no single standard for determining a ‘correct’ federal debt capital financing strategy. However, ultra-long-dated debt allows for the cost of capital expenditures to be spread more equally over all the eventual users of the facilities provided by federal fiscal spending.

By unlocking low-cost, long-term financing through 100-year bonds, the government can address critical national needs while optimising capital allocation. Longer-term funding sources align with the planning and implementation of large-scale projects, ensuring efficient utilisation of resources and minimising budget constraints.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3DyIUCt