Following the 2008 Great Recession, large metropolitan areas were able to bounce back economically within a few years, while rural areas had not yet recovered by 2020. In new research Jonathan Rodden examines the role of public sector employment in the American economic recovery, finding that public sector’s share of employment and earnings has grown in rural areas. This in turn has meant that in much of rural America, following the Great Recession, the public sector has been the leading source of long-term job losses, hindering its economic recovery.

Following the 2008 Great Recession, large metropolitan areas were able to bounce back economically within a few years, while rural areas had not yet recovered by 2020. In new research Jonathan Rodden examines the role of public sector employment in the American economic recovery, finding that public sector’s share of employment and earnings has grown in rural areas. This in turn has meant that in much of rural America, following the Great Recession, the public sector has been the leading source of long-term job losses, hindering its economic recovery.

Rural America and slow economic recovery since 2008

In the United States, metropolitan areas recovered from the 2008 Great Recession much more quickly than rural areas. While employment reached pre-recession levels in large metropolitan areas by 2012, much of rural America had still not reached pre-recession employment levels when COVID-19 arrived in 2020.

What explains the slow rural recovery after the Great Recession? Part of the answer lies in the relatively sluggish recovery of private-sector jobs in areas like manufacturing and health care. However, a surprising fact is that a full decade after the financial crisis, in many of the most rural places, the public sector was the leading category of long-term job losses.

This was the case for two reasons. First, American local governments can expect large reductions in both taxes and intergovernmental transfers during downturns. Second, rural local governments are more sensitive to these cuts than suburban or urban governments because the public sector accounts for much larger shares of employment and wages in rural America, and many local jobs are funded through intergovernmental transfers over which rural local governments have no control.

Retrenched local public finances during recessions

State and local governments in the United States fund their activities through a mix of taxes and transfers from higher-level governments. During recessions, they must contend not only with plummeting tax revenues, but also with the prospect of declining inter-governmental grants. State governments are responsible for implementing important aspects of federal policy, especially related to health care, and they are not able to smooth their expenditures through borrowing. After much hand-wringing and intense bargaining, with the onset of every major recession, Congress negotiates a package of ad hoc special transfers to help states contend with revenue losses.

As a result of these packages, state governments are typically able to continue administering federal programs and avoid large personnel cuts. However, far more public sector jobs are at the municipal rather than state level, and prior to the American Rescue Plan assembled during the COVID-19 crisis, federal relief packages focused only on distributing funds to states rather than local governments. State governments typically do not pass this largesse on to local governments. Rather, they balance their budgets during recessions in part by cutting their transfers to local governments, who then have no choice but to cut services and shed public-sector workers like teachers and hospital employees.

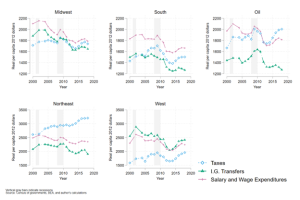

Figure 1 shows the changing real per capita taxes, transfers, and expenditures on salaries and wages for local governments by region since 2000, with a separate panel for states with substantial oil production. Tax receipts decreased everywhere (except the Northeast) in the wake of the Great Recession. Intergovernmental transfers sharply declined everywhere and did not bounce back. The same was true of expenditures on personnel.

Figure 1 – Real Per Capita Taxes, Intergovernmental Grants, and Personnel Expenditures, U.S. Local Governments, 2000-2018

The public sector and rural America

The challenge associated with declining revenue during recessions is faced by local governments in urban, suburban, and rural areas alike. However, the problem has been especially severe in rural areas, where schools and public services are increasingly funded by transfers from the state government, and where public-sector jobs have become far more important to the local economy.

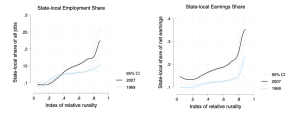

Perhaps due to media coverage of urban public-sector labor disputes, a common perception is that public employees are especially important in cities. However, as rural areas have lost population and private-sector jobs have disappeared, the public sector has come to make up an increasing share of both employment and earnings in rural areas, and rural areas now have substantially more public employees per capita than urban areas. Public sector employment has stagnated in per capita terms since the late 1980s in metropolitan America and is no larger as a share of employment today than it was in the 1960s. Figure 2 plots two different measures of public-sector dependence against an index of rurality, showing that the importance of the public sector has increased disproportionately in rural America.

Figure 2 – Rurality and Public-Sector Dependence

Note: In the facet on the left, public-sector jobs as a share of all jobs are plotted against an index of relative rurality. In the facet on the right, the vertical axis is public sector earnings as a share of net earnings. The dashed blue line is for 1969—the first year for which data were available, and the black line is for 2007—the eve of the Great Recession. The relationship between rurality and public-sector dependence was already present in 1969, but it has grown substantially in subsequent decades, especially when it comes to earnings.

The Public Sector and the Great Recession

Faced with a sudden fiscal crisis in 2008 and no recovery in sight, rural local governments had no choice but to cut their personnel costs and in so doing, reduce the number of jobs available from the largest and best-paying local employers, including school districts, public hospitals, and health clinics.

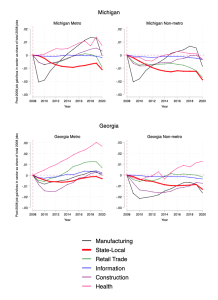

I have examined long-term job losses by employment category in each state, contrasting metro and non-metro areas, and discovered that public-sector job losses were especially slow to recover in non-metro areas, even long after other categories of employment, like manufacturing and private health care, had surpassed pre-pandemic levels. In Figure 3 for each of the largest categories of employment, for each year, I take the change in jobs in that category since 2008 and divide by the total number of jobs (in all employment categories) in 2008, highlighting two large states that are typical of those deeply affected by the Great Recession: Michigan and Georgia. In the left panel, I plot the impact of job losses over time for metro areas, and in the right panel for non-metro areas. The state and local sector is represented with bold red lines.

While public-sector job losses were more gradual than for some other types of employment, these jobs remained stubbornly below pre-recession employment levels even long after other types of employment started to recover. The impact of public-sector job losses was greater in non-metro areas. In fact, as time wore on, the public sector became the leading source of long-term non-metro job losses in some of the largest states including Florida, New York, Ohio, Georgia, and Michigan. In the non-metro counties of several states, by late in the teens, persistent job losses in the public sector were sufficient to negate the gains in other employment categories that were on the path to recovery.

Figure 3 – Impact of Various Employment Categories on Job Losses and Gains since 2008, Michigan and Georgia

I have examined long-term job losses by employment category in each state, contrasting metro and non-metro areas, and discovered that public-sector job losses were especially slow to recover in non-metro areas, even long after other categories of employment, like manufacturing and private health care, had surpassed pre-pandemic levels. Because public sector jobs were so important as a share of all employment, one decade out from the Great Recession, in much of rural America, the public sector was the leading source of long-term job losses.

Implications for Politics and Policy

This analysis raises new questions about political attitudes and behavior that are worthy of additional research. First, perhaps the boom-bust pattern of local public finance and employment, along with the reduced efficiency with which governments provide goods and services in sparsely populated areas, contribute to heightened mistrust of government in rural America. Second, rural Americans often express antipathy toward public sector unions, especially after the Great Recession. Opponents of public-sector unions criticize them for being inflexible in the face of revenue cuts and inclined to protect the perks of longstanding employees at the expense of new hires. Perhaps these critiques are most resonant in rural areas, where public-sector pay for senior employees is often perceived as high, and where job cuts during recessions are especially visible and painful.

Finally, a broad implication for policy is to explore ways of enhancing the predictability of local revenues and reducing their correlation with the business cycle, especially in rural areas, so that struggling communities are not required to fire teachers and nurses during recessions.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The great recession and the public sector in rural America’, in the Journal of Economic Geography.

- Featured image credit: Photo by Shawn Powar on Unsplash

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3P15J8C