Income inequality is on the rise in the United States at the same time as social mobility is stagnating. In new research, Luna Bellani, Kattalina M. Berriochoa, and Vigile Marie Fabella look at support for one of the key drivers of social mobility – education policy. Using California as a case study and studying draft education bills and legislators’ voting records, they find that representatives from districts with lower social mobility were more likely to favor education policies that support low-income and low-achieving students. By contrast, legislators from more affluent districts were less likely to support such redistributive policies.

Over the last 40 years, the United States has experienced an alarming increase in income inequality. At the same time, social mobility– when people’s social status improves–is stagnating. Being better off than one’s parents has become a “statistical oddity.” Researchers have long theorized that under these very conditions voters should support policies that redistribute income more fairly across people. However, we don’t often see this. One explanation claims that voters do not demand redistribution from the wealthy in hopes that their children will one day become rich. Put differently, it is often not about their direct benefit, but rather that of their children’s. This means that individuals may think about redistribution as an intergenerational investment, i.e., a way to improve their children’s prospects of social mobility. One key way in which this investment occurs is through access to education.

Education and redistribution

Education is a particularly interesting policy area for understanding what voters want in terms of redistributive policies. The people who decide on education policies–politicians and current voters– are not typically the same as those who benefit from these policies, namely students. This means that people must make decisions about what they want from an educational system with a forward-looking perspective. This begs the question of how public support of policies implemented by political representatives today will impact the outcomes of children’s social mobility in the future? In new research, we consider this longstanding question from a new angle. We ask how existing patterns of social mobility in a legislator’s district translate into their support of education policies that are more inclusive and expand opportunities.

From a first glance, expanding educational opportunities should surely generate improvements in individuals’ lives. That is, access to education will result in better job market opportunities, higher earnings, and more productivity. At the same time, it also remains true that education can perpetuate inequalities. Especially in decentralized systems like that of the United States, inequalities exist due to individuals’ circumstances and educational choices, access to different schooling options, and unequal returns across various socio-economic groups. That said, studies that focus on these inequalities emphasize that for education to motivate social mobility it is not only about expanding access but focusing this access on the most disadvantaged groups.

Photo by Arno Senoner on Unsplash

So how does the complex relationship between education and social mobility shape voters’ preferences? At least two lines of thinking seem plausible. It could be that existing inequalities hinder public support for education. Especially for low-income or disadvantaged groups the perception that education primarily benefits the higher income, resulting in concentrated advantage, could turn them away from supporting increased investments in education. These current inequalities, where the wealthy and privileged are already too far ahead, could deter and demotivate investments in education.

Alternatively, education could be seen as the ‘machine of social mobility.’ It is widely considered a “tried and true” way of ensuring that individuals lead an economically improved life compared to that of their parents. Especially in the American context, public education is seen as a fundamental part of the ‘rags to riches’ story and plays a crucial role in motivating mobility. In this reading, education provides positive benefits to people, which should result in voters demanding policies that support expanding educational opportunities, and in turn, political representatives should be receptive to their constituents. Again, both lines of thinking are plausible, which has more empirical power remains an open question.

Income mobility and support for inclusive education policies in California

To look more closely at how existing mobility shapes voters’ preferences and consequent legislative behavior, we build a model that links upward income mobility to the enactment of education policies. In this model, which we simplify here, both publicly funded education and expected upward income mobility should improve poor parents’ expectations about their children’s future economic status. This means that voters in low social mobility districts should be more supportive of redistributive educational opportunities and, assuming representation, politician’s support of these policies will be more in-line with that of their constituents. Inversely, politicians’ support of redistributive educational policies will weaken as district level upward mobility increases.

Using data from California, we examine this idea that low social mobility results in more support of expanding education. California provides an important case for studying this notion. It has been the site of important judicial decisions and public referendums that have impacted school funding formulas, school equalization efforts, and resulted in a well-known “tax-payer revolt,” in which affluent districts supported property tax caps to avoid redistribution that did not benefit their local district. Most importantly for our research, California remained a highly centralized educational system, in which state legislators made the bulk of policy decisions, until 2013.

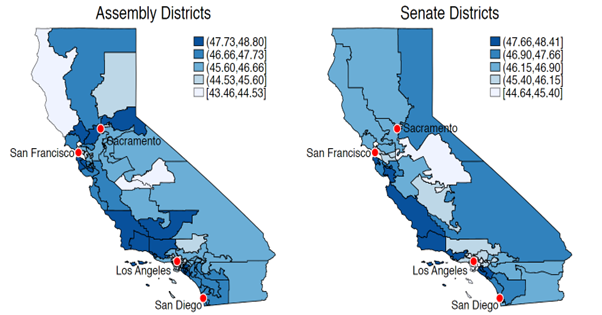

Using drafts of education bills and voting outcomes by the state legislature from 2007-2013, we examine inclusive education policies (those that affect low-income and low-achieving students and provide school access to those who would otherwise be outside the system). Examples of these policies include tuition assistance, early childhood education, and technical education. We also rely on data on absolute upward mobility, measured as the mean percentile rank in the national child income distribution of children with parents at the 25th percentile of the national parent income distribution. To have a better sense of what this means in terms of income, children with parents at the 25th percentile of the national parent income distribution in our sample are on average doing better in their mid-20s, around the 46th percentile of the distribution (which in 2012 corresponded to an income of $31,100). As Figure 1 shows, within California, districts along the coastline between San Francisco and Los Angeles show generally higher trajectories of absolute upward mobility.

Upward mobility is linked to legislators’ opposition to more inclusive education policies

In our empirical analysis, we find clear evidence of a positive association between upward mobility in legislators’ districts and their opposition to redistributive (inclusive) education policies. This supports our theoretical prediction that a decrease in upward mobility increases support for inclusive education policies. That is, political representatives from low-social mobility districts are more likely to support the enactment of education policies that support low-income and low-achieving students.

Figure 1 – Upward mobility across legislative districts, 2007–2012.

Note: The color scheme corresponds to values that divide the distribution of the average percentile rank in the income distribution of the children in the districts into five equal-width intervals. For example, children with parents belonging to the lowest 25th percentile of the income distribution belong, once adults, on average, to the 43rd–44th percentile of the income distribution in districts where mobility is the lowest.

What does this mean for education as the “great equalizer”? Education policy is becoming increasingly politicized in the US with state legislatures becoming hot-beds for policy debates about school funding, parental choice, and design of curricula. Our research suggests that the expansion of educational access remains an important mechanism for individuals and legislators in low-social mobility environments. Considering recent political efforts to reshape systems of public education, it is important to note that jeopardizing education as a tool for promoting mobility will disproportionately hurt the futures of those with the largest gains to be had from expanding educational opportunity, namely disadvantaged students. In this sense, current trends in the politics of education could perpetuate existing inequalities, resulting in even fewer individuals experiencing social mobility.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Social mobility and education policy: a district-level analysis of legislative behavior’ in Socio-Economic Review.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/40KIfcb