Those with college degrees generally have higher incomes compared to those who do not – but not everyone with a college degree benefits from the same increased earning potential. In new research, Dirk Witteveen and Paul Attewell look at how the concentration of certain undergraduate majors within occupations can influence earnings. They find that occupations are linked to higher incomes when they have a greater density of people with particular college majors. These income boosts are over and above skill-based rewards, a finding they attribute to those within the occupation with the same college major acting as employment gatekeepers.

Those with college degrees generally have higher incomes compared to those who do not – but not everyone with a college degree benefits from the same increased earning potential. In new research, Dirk Witteveen and Paul Attewell look at how the concentration of certain undergraduate majors within occupations can influence earnings. They find that occupations are linked to higher incomes when they have a greater density of people with particular college majors. These income boosts are over and above skill-based rewards, a finding they attribute to those within the occupation with the same college major acting as employment gatekeepers.

The college degree earnings premium, typically measured as the gap between the average earnings of graduates with a bachelor’s degree and high school graduates, has grown steadily over recent decades. Economists attribute this to ever-growing demand for educated workers in the service sector and high-tech industries. College degrees help individuals enter jobs that are rewarded with increasingly higher salaries compared to the rest of the economy. However, payoffs from higher education are far from equally distributed. The best explanation for this diversity of incomes is the skill variation captured by college majors.

We argue that there are at least two other ways in which college majors can be linked to earnings inequality: the context matters. First, we show that the concentration of undergraduate majors within occupations is positively associated with occupational-level earnings. Second, we find relatively small earnings penalties for individuals who “mismatched” their college degree with their occupation.

Earnings are not just determined by people’s skills

We know that earnings variation between occupations is not only a function of the occupation’s skill payoffs, but also of the capacity of occupational incumbents to channel demand, restrict the labor supply, and signal quality. Institutionalized strategies that help restrict the number of possible competitors in an occupation, such as licensing and educational credentials, can “artificially” boost the earnings of an occupation. These credentials provide some indication of quality (e.g., dieticians and nurses), but at the same time offer those already working in the profession a tool to control the labor supply of the occupation. Together with collective bargaining, licensing, and credentialing form “closure devices” that are associated with higher occupation-level rewards, over and above human capital payoffs. If fewer individuals are admitted to a particular occupation, incumbents can simply ask more for their services. Scholars have reported evidence for “closure effects” in various high-income countries. Does the college major serve as an occupational closure device that boosts earnings over and above its rewards for people’s skills? If college majors help control access to an occupation, a higher density of particular college majors within occupations should be associated with higher earnings in that occupation.

To answer this question, we use microdata from the American Community Survey. We focus on 230 occupations representing the higher-educated segment of the labor market (1.4 million cases). We use a measure of occupational specialization and track the level of college major differentiation and specialization within occupations. We argue that this measure can tell us whether the college major is activated as closure device if we control for occupation skill-level and individual-level covariates of earnings (“human capital”).

College majors and occupational earnings

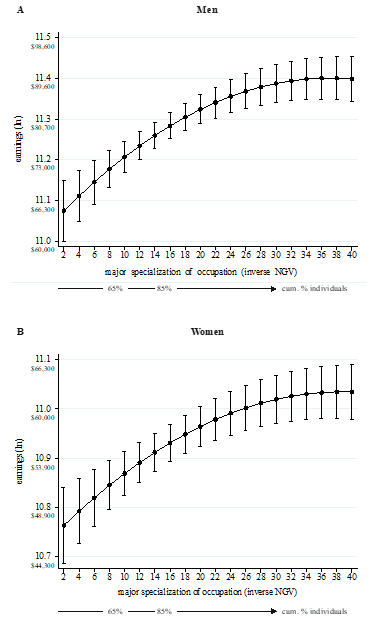

We find that the level of an occupation’s major specialization is strongly associated with occupational earnings. Figure 1 shows the effect size of college major density. The strength of the association between occupational major specialization and earnings is similar for men and women, though women earn less on average.US college majors do form barriers for occupational entry, and this creates an earnings boost enjoyed by all those currently in that occupation, over and above the occupation’s skill-level payoffs and worker’s characteristics.

Figure 1 – Marginal Effects of Major Specialization of Occupations.

Having the same college major as others in an occupation can help earnings

We next turn to the role of college majors in earnings variation at the individual level. Again, we consider the context of graduates’ employment. The dominant explanation for college major payoff variation is that different majors indicate different levels of human capital. For example, assuming there’s a high demand for technical services, we might expect workers who hold a “STEM major” to earn more than, say, sociology majors (assuming there’s less aggregate demand for sociological analysis). But what if the STEM graduate becomes a high school teacher? Or what if the sociology major becomes a tax agent? Do they earn more or less than their counterparts who “matched” their college major with their occupation?

We examine the “major-occupation” match organically rather than using dichotomous indicator (matched vs. not matched). We calculate for each person the percentage of workers in their occupation who hold the same college major. While this matching percentage is quite high for graduates in occupations such as nursing, where almost everyone holds the same nursing degree as the respondent, the major-occupation match practically ranges between zero to 72 percent.

Photo by Tim Alex on Unsplash

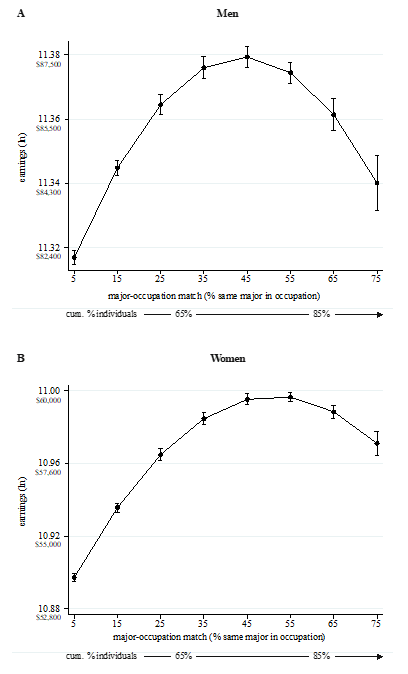

Figure 2 shows that we find a significant positive association between major matching within occupations and earnings. A 10-percent increase in the share of workers holding the same college major within the occupation as the individual is associated with 3.6 percent (men) to 4.8 percent (women) higher earnings: a couple of thousand dollars annually. Hence, yes, a stronger major-occupation match is beneficial, but the relative advantages remain small. The relationship is also not linear: very strong major-occupation matches do not yield extraordinarily higher pay.

Figure 2 – Marginal Effects of Major-Occupation Match on Earnings

The importance of occupational gatekeepers

College majors explain a large share of earnings variation among higher-educated individuals in the workforce. Economists argue that these college major “effects” are payoffs from human capital, such that the variation in college major earnings payoffs more or less reflects the “demand” for skills obtained in higher education programs and applied in particular occupation. We do not disagree with this perspective on the role of college majors in earnings inequality. In fact, this intuitive relationship is reflected in our results, where undergraduate majors are consistently predictive of earnings.

However, our sociological perspective considers the context of college major payoffs, revealing differences in earnings stratification among college graduates. We show that occupations differ in the extent to which they can generate earnings boosts over and above their supply-and-demand based rewards for skills. We argue that a high density of a particular college major within an occupational niche allows its incumbents to control access, thereby bidding up the total income of the occupation. Creating barriers for occupational access – “you need this particular credential and license to get this job” – helps incumbents, but likely deprives outsiders with similar skillsets from accessing this market income.

Furthermore, college majors pay off slightly more if the college graduate enters an occupation where their colleagues hold the same major. We consider earnings advantages to be relatively small. College majors matter for getting access to particular occupations, but within occupations workers with different majors earn fairly similar salaries. This suggests that while skills obtained in college programs matter for earnings, individuals with different qualifications are still rewarded at similar levels as their colleagues.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Closure and matching payoffs from college majors’, in Socio-Economic Review.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-dw5