Climate change is not just an environmental issue, but also one of economic transformation, writes Thomas Oatley. In new research, he uncovers what he terms, the ‘carbon-climate cleavage’, where voters in some areas of the US experience the impacts of climate change more than others, and some live in areas with remaining carbon-intensive industries while others reside in places focused on knowledge intensive industries. He writes that carbon economy communities are more likely to support Donald Trump because they believe his policies will sustain the carbon economy, while knowledge economy communities support Joe Biden because they believe he is more likely to make climate change a priority.

Climate change is not just an environmental issue, but also one of economic transformation, writes Thomas Oatley. In new research, he uncovers what he terms, the ‘carbon-climate cleavage’, where voters in some areas of the US experience the impacts of climate change more than others, and some live in areas with remaining carbon-intensive industries while others reside in places focused on knowledge intensive industries. He writes that carbon economy communities are more likely to support Donald Trump because they believe his policies will sustain the carbon economy, while knowledge economy communities support Joe Biden because they believe he is more likely to make climate change a priority.

The climate crisis contributes to the polarization of contemporary American politics to an extent and in ways that are not yet generally appreciated. We typically treat climate change as an issue of environmental policy, but we less often recognize that climate change also is an issue of economic transformation. Climate change policies such as the Inflation Reduction Act are working to change the foundations of what powers our industries as well as the industries themselves, a process that brings significant adjustment and dislocation to the affected communities. As the climate crisis accelerates, the ongoing transition from one economic model to another, the American electorate has become divided in a way that is not easily bridged.

Climate change and the shift to the dual economy

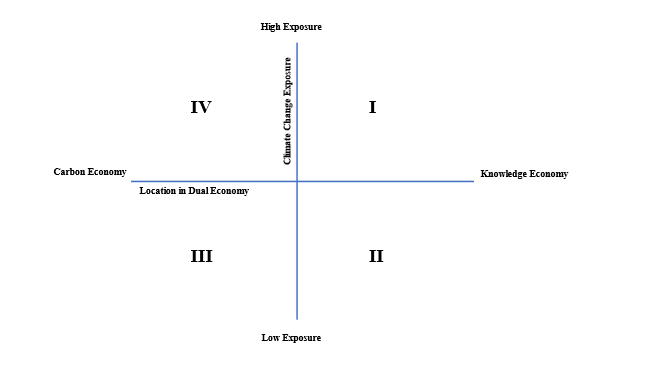

In new research, I think about the underlying issue as a two-dimension issue space (see Figure One). Exposure to climate change impacts is the first dimension. Because the US is so large, some voters are more directly exposed to the severe weather events that climate change generates, such as rising sea levels, coastal erosion, droughts, floods, hurricanes, and forest fires, than others. Voters are thus distributed across this climate change dimension from high to low exposure. For voters in high exposure regions, climate change constitutes an existential threat, and they have strong reason to support climate change policy. For voters living in areas with considerably less direct exposure, climate change remains a remote and rather expensive threat to address.

Figure 1 – The Carbon-Climate Cleavage

The dual economy is the second dimension. Whereas for most of the 20th century the US had a singular economy centered on carbon-intensive industries, today it has a dual economy. One economy contains the remaining carbon-intensive industries, such as manufacturing, that produced the middle class in the 20th century. Here we find communities that remain heavily dependent on activities such as resource extraction and processing, as well as carbon-intensive manufacturing for jobs, tax revenues, and general community well-being. The other economy contains the knowledge intensive industries that are driving growth in the 21st. These communities rely on industries such as high tech, financial services, and entertainment to provide high paying jobs and the tax revenues that fund local infrastructure and public services. Voters are distributed across this dimension from being fully dependent on carbon intensive industry to being entirely in the knowledge intensive economy with little-to-no involvement in carbon-intensive industries. Even power-hungry data centers can run just as effectively on electricity from renewables as on electricity generated using fossil fuels. Voters in carbon economy communities want to sustain the carbon economy, while voters in the knowledge economy communities see little need to do so.

Photo by Anne Nygård on Unsplash

Where Americans live amplifies the carbon-climate cleavage

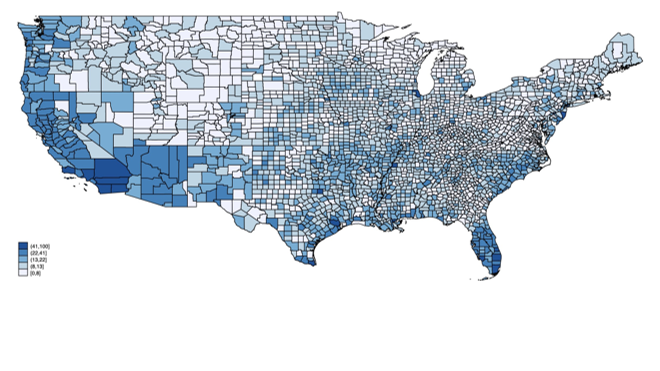

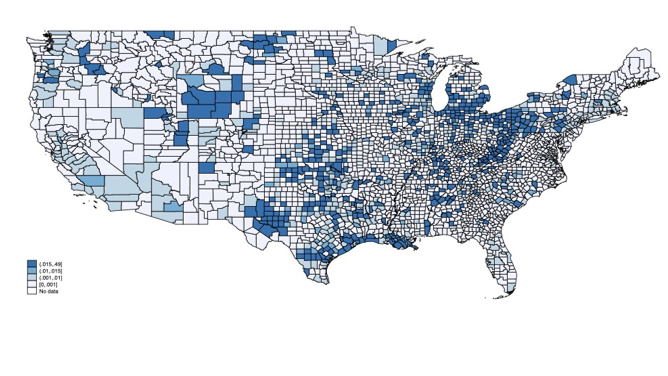

The American electorate is distributed across this space in a way that amplifies rather than dampens the differences that exist on each dimension. Roughly forty percent of the electorate lives in knowledge economy communities that are relatively immune to decarbonization but highly vulnerable to climate impacts (see Figures 2 and 3). These voters want aggressive climate policy that rapidly phases out carbon-intensive industries and the fossil fuels that sustain them. And while such policies protect their interests, they also constitute a direct threat to carbon economy communities. Another forty percent of the electorate lives in carbon economy communities that face high costs from decarbonization but appear to be insulated from major climate impacts (Figures 2 and 3). Voters in these communities oppose decarbonization initiatives, preferring instead to enact small emissions reductions and to bet on emerging technologies (such as carbon capture) to address the negative effects that using fossil fuels generates. Such policies obviously protect their communities but only by imposing high costs on coastal regions as the climate crisis worsens. This division of the American electorate is what I call the carbon-climate cleavage.

Figure 2 – FEMA National Risk Index, 2021

Figure 3 – Carbon economy jobs

This divide was evident in the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections and will feature significantly in the 2024 election as well. Support for Donald Trump was strongest in carbon economy communities with low exposure to climate change, while his support was weakest in knowledge economy communities with high exposure to climate change. Carbon economy communities support Trump at least in part because they believe he will attempt to sustain the carbon economy. Knowledge economy communities supported Hillary Clinton and President Joe Biden because they believe they are more likely to make climate change a priority. Moreover, even when we consider the impact of ideological and identity on support for Trump, communities’ position in the dual economy and relative exposure to climate change remain highly correlated with support for Trump.

Bridging the carbon-climate cleavage

My analysis has two clear implications for contemporary politics and policy. First, the Biden administration’s approach to distributing Inflation Reduction Act spending offers the best chance to bridge this cleavage in the short term. The administration’s strategy has been to focus heavily on Red States, carbon economy communities with low exposure to climate change impacts, to broaden the coalition that supports climate change policy. Second, the success of the administration’s strategy depends on the outcome of the 2024 election. Should Biden win, the administration will have another four years to build on their initial success. A Republican victory, however, is likely to reverse climate policy and squander the progress made so far.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The dual economy, climate change, and the polarization of American politics’, in Socio-Economic Review.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3HABm4q