Primary elections have an important role in determining the ideological makeup of the US Congress. In new research, Mike Cowburn and Marius Sältzer analyze Twitter/X posts from candidates in primary elections for the House of Representatives to determine the extent to which they maintain their political positions after winning their primary election. They find that while winning candidates from both parties do maintain their positions, after losing a primary, Democrats change their positions while Republicans do not. This suggests that at least some primary candidates may be adopting artificial positions during the nomination process, which can subsequently worsen polarization when they are elected to Congress.

Primary elections have an important role in determining the ideological makeup of the US Congress. In new research, Mike Cowburn and Marius Sältzer analyze Twitter/X posts from candidates in primary elections for the House of Representatives to determine the extent to which they maintain their political positions after winning their primary election. They find that while winning candidates from both parties do maintain their positions, after losing a primary, Democrats change their positions while Republicans do not. This suggests that at least some primary candidates may be adopting artificial positions during the nomination process, which can subsequently worsen polarization when they are elected to Congress.

Every two years all 435 members of the US House or Representatives face re-election, but not all these contests are equally competitive. In fact, according to one source, in the 2022 elections, only 36 races were true “toss-ups” and 291 were either landslides or completely uncontested. With the outcome of so many elections essentially pre-determined, it’s clear that primary elections – where party members decide on their candidate – can be very important in determining the ideological makeup of Congress.

Do primary elections make polarization worse?

Whether primary elections are contributing to growing polarization in Congress remains keenly debated in the academic literature. Primary elections are commonly said to increase the ideological distance between Republicans and Democrats in the legislative branch because of the preferences of those voters who are engaged and enthusiastic enough to turn out to vote in them. Yet, past studies identify little in the way of positional differences between parties’ primary and general electorates.

Our research takes a different approach to the question of partisan polarization and primary elections. Rather than focus on the voters, we analyze how candidates communicate in contested congressional primaries. Primaries are said to incentivize candidates to move away from the center ground, either to appeal to likely voters or other important groups in the party network. We try to identify ‘artificial’ positioning further away from the center than would have been otherwise taken by Republican and Democratic candidates in the 2020 House of Representatives’ primary elections by scaling their communication on Twitter (now X) both during and after the primary. We expect that primary winners will maintain positions taken during the primary to prevent accusations of “flip-flopping” and instead expect that changes will only be observed among primary losers after their defeats.

To construct our data, we apply a text-as-data approach using supervised machine learning to identify the level of partisanship of more than 2.5 million tweets by almost 1,000 candidates. We demonstrate the validity of this approach by correlating our results with rollcall votes in the US House where possible, with a correlation of 0.93.

“Primary voting in St Paul, Minnesota” (CC BY 2.0) by Lorie Shaull

Democrats change their positions after losing a primary, Republicans don’t.

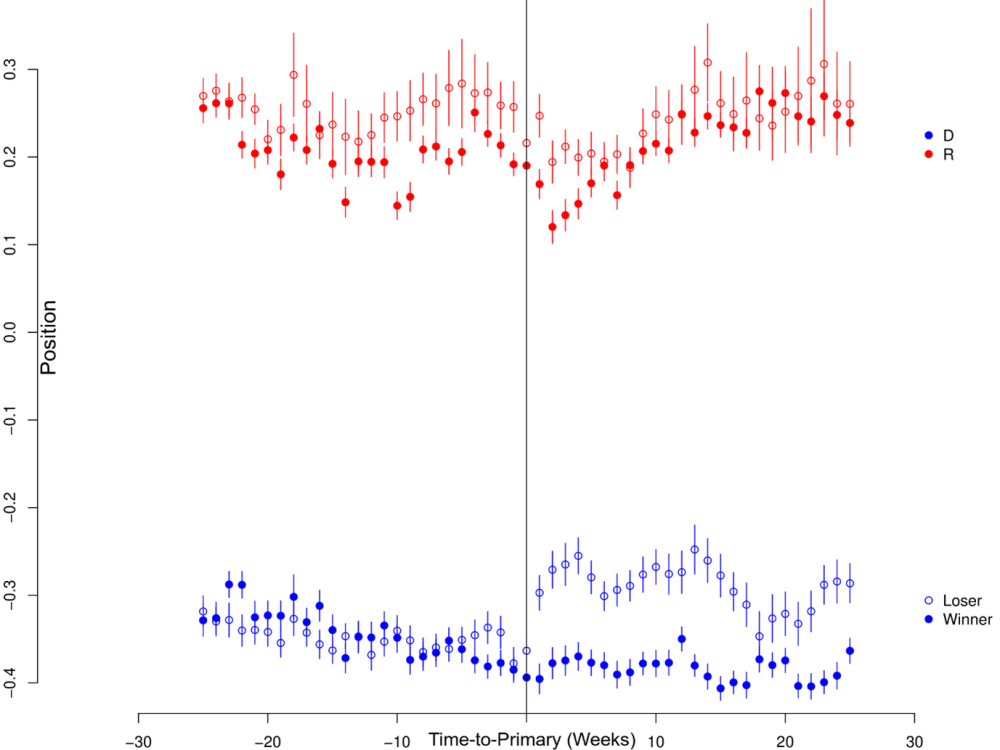

We find that losing Democratic candidates moderate after the primary election. This moderation is substantively meaningful and statistically significant. Conversely, we find no equivalent shift in the position of losing Republican candidates. Our results, shown in Figure 1, indicate that primaries are associated with artificial position-taking among Democratic candidates only. We interpret these findings as support for the strategic positioning dilemma among Democratic candidates, who adopted artificial positions during the primary which they did not continue to hold once absent the (perceived) incentives to do so. Among Republican candidates, we find minimal evidence of artificial positioning, suggesting that communication during the primary was done out of conviction rather than for perceived advantage. Absent electoral incentives, losing Republican primary candidates continued to communicate highly conservative positions.

Figure 1 – Ideological position of Democratic and Republican primary candidates

For general election voters, these results are not encouraging when considered in terms of how we think about and model how people vote. Given that we find limited evidence of moderation among primary winners in either party, voters in November appear to have been presented with polarized choices for contrasting partisan reasons, with Democratic candidates having strategically adopted artificial positions during the nomination and Republicans sincerely holding their non-centrist positions out of conviction. That Democratic primary winners don’t moderate their views, may indicate a perception among candidates that they must continue to hew to the preferences of groups in the party beyond the primary or reflect candidates’ beliefs about the electoral risks associated with moving positions between a primary and general election. Among Republicans, our findings suggest limited adaptation, and positions appear more deeply ingrained in the preferences of candidates.

Many studies analyzing whether primaries contribute to partisan polarization in Congress only focus on a selective effect from primary voters. Our research identifies a further way in which contested nominations may make partisan conflict in Congress worse: the adaptation of candidate positions during the nomination phase of the election cycle. If many candidates perceive that communicating artificial positions is beneficial during the primary and then feel compelled to maintain those positions during the general election, voters in November will be presented with more polarized choices because of the nomination process. More positively, we find little movement among nominees in either party once they are selected. Regardless of whether candidates adopt sincere or strategic positions, primary winners communicate positions in general election campaigns that are consistent with their positions during the nomination.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Partisan communication in two-stage elections: the effect of primaries on intra-campaign positional shifts in congressional elections’ in Political Science Research and Methods.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3Uomv4v