To tackle global challenges like climate change, it’s clear that tougher policies may be needed to change behavior. Chris Koski and Paul Manson write that policymakers often shy away from imposing costs and burdens on powerful and popular groups because of concerns that voters might dislike these policies. In new research, which looks at public attitudes towards climate change policies, they find that while people might favor capacity building tools such as climate subsidies for the deserving, there is also strong support for burdening the powerful with policies such as carbon taxes and cap and trade.

To tackle global challenges like climate change, it’s clear that tougher policies may be needed to change behavior. Chris Koski and Paul Manson write that policymakers often shy away from imposing costs and burdens on powerful and popular groups because of concerns that voters might dislike these policies. In new research, which looks at public attitudes towards climate change policies, they find that while people might favor capacity building tools such as climate subsidies for the deserving, there is also strong support for burdening the powerful with policies such as carbon taxes and cap and trade.

Policymakers often face hard choices when distributing benefits and burdens in the design of public policies. While it might make sense from a policy perspective to direct burdens and costs on strong groups who can bear them (and often because these groups are responsible for harm), the reality is, taking on established interests can be politically difficult. Policymakers are not only concerned that powerful groups will punish them for imposing burdens, but also may be concerned that the public will be less receptive to efforts that attempt to burden popular groups (though they may be powerful). Conversely, weaker groups and groups that are seen as undeserving may not provide benefits to policymakers if they direct benefits to them. Thus, policy designs often offer imperfect solutions in part because of policymakers’ perceptions that designs that burden the strong and benefit the weak will be received well by the electorate. Without the goodwill of the powerful, public policies designed to address the challenges of our times are locked in a cycle that only changes in ways that benefit established interests.

The dilemma of climate change burdens

This dilemma is particularly noticeable in climate change where powerful groups – including those that are both positively (e.g. the military) and negatively (e.g. large technology firms) constructed – ultimately contribute to climate harms more than weaker groups, while also possessing a greater capacity to address those harms. In the United States, climate policies are generally focused on providing benefits to all groups – though the bulk of these funds are often directed at powerful institutional actors – and providing very few burdens. Presumably, policymakers might be more amenable to burdening powerful groups if they knew it were in their electoral interest to do so.

“Construction worker, Doug Berger, helps” (CC BY-NC 2.0) by EE Image Database

Our new work offers some insights into addressing this dilemma. Our national survey experiment confirms that as new policies are developed to address climate change, they must consider who will benefit from or be burdened by these policies (referred to as target populations). We find that public acceptance or opposition to climate policies hinges on perceptions of the deservingness of target populations. We also learned that to a lesser degree, perceptions of who are powerful in society also shifts the acceptance of policy choices. Some policy tools, when combined with certain groups in society, can produce unexpected support and opposition – suggesting that the tools we use in policy making can override perceptions of the groups they are targeting. Notably, our research shows there is a significant appetite among the public to burden the powerful when it comes to climate policy, even those that are perceived as deserving.

Considering Climate Policy Design: Tools and Target Populations

Our research examines public attitudes towards distinct policy tools that address a variety of mitigative (increasing renewable electricity use, reducing emissions, and increasing electric vehicle use) and adaptative (planning for areas highly vulnerable to climate change, taking steps to protect from extreme heat events, and reducing water use) climate policies directed at different target populations. We looked at four tools that would benefit each target populations (increased government research, exemptions for policy requirements, increases in government funding, and government ad campaigns to highlight positive activities of target population) and three tools that would burden target populations (requirements to undertake actions, government ad campaigns to highlight negative activities of target population, and fines directed at noncompliance).

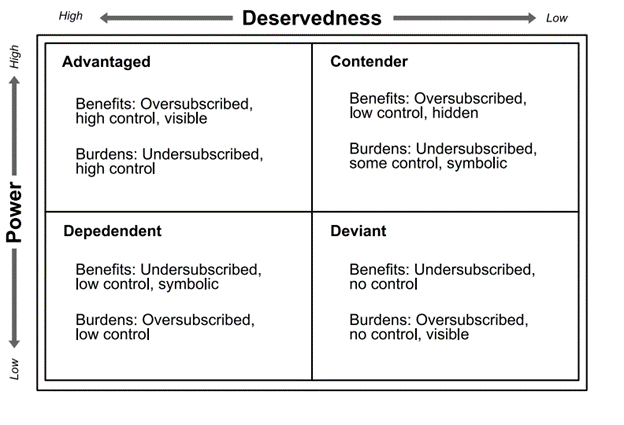

We use a previously developed typology of target groups which proposes that different populations for policies can be arrayed along two dimensions: deservingness and power (see Figure 1 below). In their 1997 work, political scientists Anne Schneider and Helen Ingram identified four types of target populations: Advantaged, Contender, Dependent, and Deviant. Advantaged groups are lauded in society and perceived as having resources (we use the Military in our survey experiment). Contenders are groups that have power but are not perceived as deserving or potentially have outsized power (we use large technology companies). In the lower half of the table are those groups perceived as having less power. Dependents are deserving but for various reasons are not allocated a comparable share of power (we use small farmers). Finally, deviants are groups with low power and low deservingness (we use undocumented immigrants).

Figure 1 – Deservingness and power typology

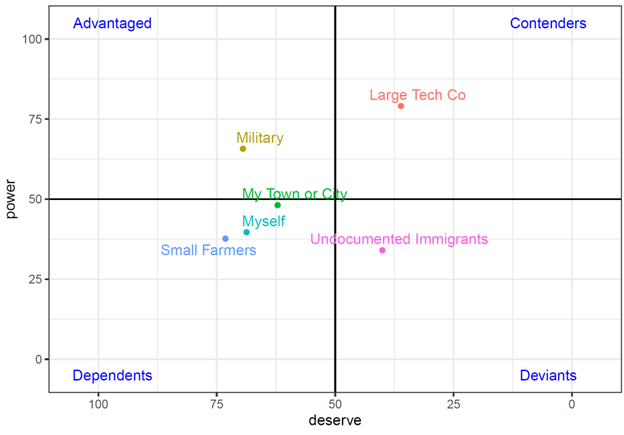

Previous research (see Donovan 1993) has focused on how policy makers see these dimensions across groups. Our research asks the same question of the public, to understand if these same images are durable for them. We know from more recent work (see Bell 2021) that there are feedback loops that impact public perceptions. Policies themselves reallocate power and to some degree perceptions of deservingness. This means policies can send a cue to the public about who is powerful or deserving. The placement of our survey respondents (see Figure 2 below) matches our expectations of group placement, though there is particularly strong agreement on large tech firms as powerful and undeserving. For reference, we ask respondents to rate their own power and deservingness as well as that of their town or city.

Figure 2 – Group placement and deservingness and power typology

Who wins matters, but how the winners are managed matters too

We find, in general, that deservingness is associated with positive attitudes toward policies that have benefits – particularly capacity-building benefits such as increased government funding – while power is less predictive of benefits. Our research shows that, while apparently expedient in the Congressional politics of policymaking, capacity building tools are judged by the public based on who is most deserving, rather than who has or lacks power. These capacity-building tools may be a kind of lowest common political denominator necessary to do something about climate change, but this tool choice reinforces the advantages that deserving groups have – particularly powerful deserving groups.

However, we also find that while people might favor capacity building tools for the deserving, there is also strong support for burdening the powerful. Not only might politicians be seen favorably by constituents for doing so, but such policy interventions are likely to be necessary in combating the production of greenhouse gases and preparing people for a warming planet. Our work finds that requirements and punishments for even advantaged populations (high deservingness, high power) are viewed favorably – though, not as much as those directed at undeserving groups. When governments do create climate requirements, they often design exemptions for groups – particularly those that are powerful. Our work shows that these exemptions are very unpopular when directed at powerful or undeserving groups (or both).

In broad strokes, then, our US-based respondents are generally in favor of burdening the powerful which has implications for public policy. Most federal legislation in climate change policy has not been regulatory, but rather capacity building.

Why politicians should consider reaching for the stick on climate

Cap and trade (which creates a tradeable permit system for emissions) in the form of the Waxman-Markey bill famously failed in 2010, when Democrats controlled both chambers of Congress and the White House. The Clean Power Plan under the Obama administration was offered, revamped for a year, and then eventually undone by the Trump Administration. Carbon taxes have thus far been something akin to a legislative kiss of death. The Biden Administration was able to score a major climate victory in the form of the Inflation Reduction Act, but the mechanisms of this act are mostly (if not entirely) in the form of subsidies (which we characterize as benefits).

Thus, a practical conclusion from our work is that politicians do not need to shy away from regulations or taxes. In other research where we directly query US respondents about broader climate policies, we find that there is generally more support for regulations than there is for more commonly pursued policies such as taxes on high income earners, carbon taxes, and particularly cap and trade. Our findings should embolden policymakers to adopt a stick approach to climate policy rather than the current carrot-dominated portfolio in the United States. The political opportunities to take the next step in a more assertive federal climate policy are there should the Congress wish to take them.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Policy design receptivity and target populations: A social construction framework approach to climate change policy’, in Policy Studies Journal.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/49nW6YY