The LSE Phelan US Centre’s Capitalism Essay Competition asked LSE Master’s students to address the question, “How should the United States work to shape the future of capitalism in this age of insecurity?” In this runner-up essay, Manickam Valliappan writes that rising inequality is a clear signal that there are defects in capitalism that warrant expansive action. He argues the US should shift from a paradigm of redistribution to “pre-distribution” to prevent inequality rather than treating its symptoms. The US should consider domestic policies such as incentivising human-friendly AI technologies, equalizing tax rates between labor and capital, worker-friendly labour market regulation, and place greater emphasis on upward social mobility.

The LSE Phelan US Centre’s Capitalism Essay Competition asked LSE Master’s students to address the question, “How should the United States work to shape the future of capitalism in this age of insecurity?” In this runner-up essay, Manickam Valliappan writes that rising inequality is a clear signal that there are defects in capitalism that warrant expansive action. He argues the US should shift from a paradigm of redistribution to “pre-distribution” to prevent inequality rather than treating its symptoms. The US should consider domestic policies such as incentivising human-friendly AI technologies, equalizing tax rates between labor and capital, worker-friendly labour market regulation, and place greater emphasis on upward social mobility.

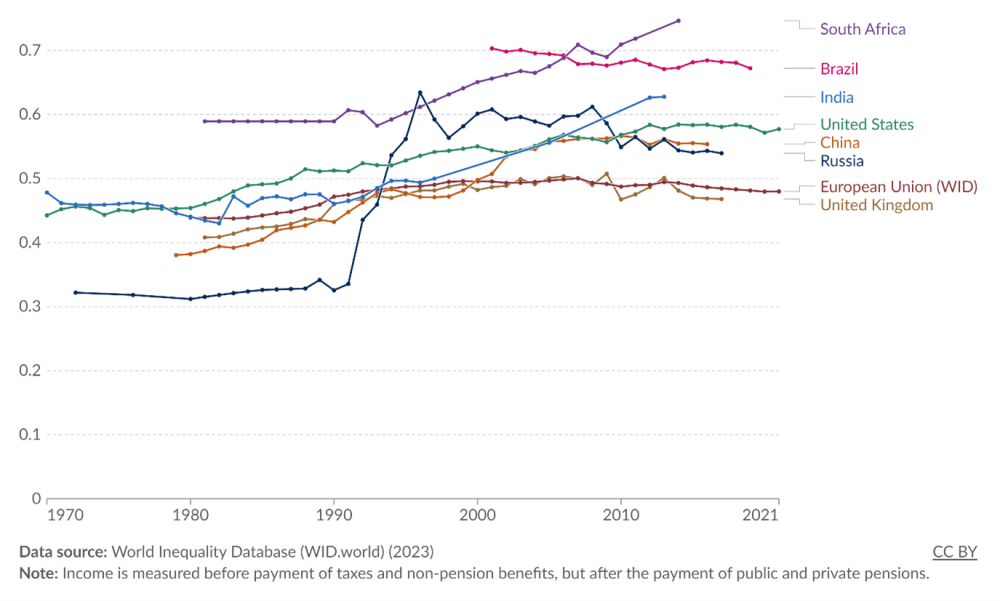

Capitalism has lifted millions out of poverty and has led to rapid technological progress – yet it still refuses to work for some. The top 1 percent accounted for nearly 31 percent of total net worth in the US, with a general increasing trend in income inequality observed in the US and other major market economies. A worrying observation is how economic inequality is entrenched in rigid social structures: according to a Brookings report, in the US, nearly half of those in the bottom quintile of wealth in their early thirties stay there in their fifties. Moreover, nearly one third of children who grew up poor in the US tend to stay poor, signalling persistent cycles of intergenerational poverty. These are clear signals that there are inherent defects within modern capitalism that warrant expansive action.

Figure 1 – Gini coefficient, 1970 to 2021

Note: The Gini coefficient measures inequality on a scale from 0 to 1. Higher values indicate inequality. Inequality is measured here in terms of income before taxes and benefits. Note: Income is measured before payment of taxes and non-pension benefits, but after the payment of public and private sector pensions. Data Source: World Inequality Database (WID.world) (2023)

Redistribution via higher taxes is often cited as a key fix for such inequalities. But relying on redistribution as the only fix still treats declining social mobility as a second-order priority. What the US and the world needs is a paradigm shift to “pre-distribution”, which prevents the generation of inequalities rather than relying on measures that treat its symptoms. This is rooted in the realization that equal opportunities are far from automatic. Research suggests that different factors ranging from the neighbourhood where one lives to the race that they belong to play a pivotal role in determining access to quality education and healthcare.

What must then follow is US government action in crafting meticulously designed policies such as expanding access to education and healthcare, coupled with stronger labour protections. Shifting the frame from a firm-driven capitalistic model to a model that emphasizes the capabilities of individuals to participate effectively must be a key tenet of Capitalism 2.0. Notably, a comparative study found that the US’s high inequality relative to Europe was due to a dearth of pre-distribution policies such as unionisation, labour market regulation, and access to education.

Inclusive technological progress

Technological advances are also bound to aggravate existing inequalities. Free markets assume that technology leads to increases in overall productivity, hence driving economic growth. But to assume that such growth would automatically accrue to all individuals in society would be wishful thinking. Historically, concentrations of wealth have often followed technological progress. This is especially relevant in the context of progress in Artificial Intelligence, which favours skill-biased growth. According to an IMF study, nearly 40 percent of jobs are exposed to AI, with the number shooting up to 60 percent for the developed world. Half of these jobs are expected to be negatively impacted. While one can argue that this pushes for upskilling labour, such processes are not automatic.

Nevertheless, constraining technology to ease potential negative impacts is akin to throwing-the-baby-out-with-the-bathwater. Technological progress, especially in AI, will be key in solving pressing issues such as climate change, which also poses an existential problem for capitalism. As Daron Acemoglu argues, the solution lies in the US incentivising development of more human-friendly technologies that can be adapted in different sectors such as health care and education, which in turn facilitates more employment. Equalizing tax rates between labor and capital – which is currently biased against labor – can also ensure more human employment and prevent excessive automation that leads to low productivity gains but higher worker displacement.

Barriers to pre-distribution: equity vs efficiency

Reluctance in embedding pre-distribution policies within US’s existing capitalistic economy stems from concerns over equity-efficiency trade-offs. Aiming for equity as an end-goal, as the argument goes, will hamper incentives in a free market and lead to overall welfare losses. There is some credence to this argument – excessive intervention can indeed hamper economic progress by “distorting” the market. But there is still some room for prudently designed policies that are both equitable and aid in economic growth. For instance, carefully targeted policies such as modest increases in minimum wages coupled with tax benefits can yield overall benefits for low-income earners without a negative impact on employment. Technological redirection is also not a new concept, evidenced by the US government’s role in incentivizing innovation in renewable energy. An IMF study found that equity and long-run economic growth were two sides of the same coin, underlining the importance of pursuing equitable outcomes.

Apart from leading by example via pursuing domestic policies that bridge inequalities, the US must also place upward social mobility at the centre of the rules-based-order. This would ensure that the waning trust in globalization throughout different parts of the world is slowly restored. One way to do so is by actively enforcing worker-friendly provisions within multilateral institutions. Provisions such as commercial sanctions for labour violations within trade agreements can prove effective in diffusing labour protections.

Reforming capitalism is not just an economic problem.

Another major revamp lies in the very way the US conceptualizes capitalism and the institutions and policies that underpin it. There is no doubt that economists will have to play a pivotal role in the discourse around reforming capitalism, but economic issues are also embedded in various social, political, and historical contexts. Factors such as place and race matter. The anti-globalization rhetoric resonates strongly along geographic lines and is the strongest in places which are on a long-term social and economic decline. Black people often lack the social networks that white people enjoy for better opportunities. These problems call for interdisciplinary policy designs that integrates different social science perspectives. The US needs to come to terms with the fact that most of the problems with capitalism are not just rooted in top-down economics.

The road ahead for reforming capitalism is far from simple, but it is within reach. The US, with its cultural and economic might, needs to play a key role in this regard by shifting its policy priorities to capability building that encourages upward social mobility. The viability of capitalism depends on how the US answers a simple yet fundamental question: what is the point of a bigger pie, while some continue to starve?

- Photo by Kayle Kaupanger on Unsplash

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-dCx