Under US law, those who are paid to lobby the government and members of Congress must register formally as lobbyists. Mathieu Rojas Egoavil, Brian Libgober, and Daniel Carpenter describe new research on the extent of “regulatory lobbying” by lawyers who are seeking to influence regulators and regulation, but who do not need to register as lobbyists. They estimate that five major Bank Holding Companies are spending up to $458 million per year on regulatory advocacy – more than 20 times the value of their reported lobbying expenses.

Under US law, those who are paid to lobby the government and members of Congress must register formally as lobbyists. Mathieu Rojas Egoavil, Brian Libgober, and Daniel Carpenter describe new research on the extent of “regulatory lobbying” by lawyers who are seeking to influence regulators and regulation, but who do not need to register as lobbyists. They estimate that five major Bank Holding Companies are spending up to $458 million per year on regulatory advocacy – more than 20 times the value of their reported lobbying expenses.

In the wake of the Great Recession, Congress enacted the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act of 2010, the most significant overhaul of the US financial regulatory system since the Great Depression. Because of the complexity of this undertaking, the Democratic majority in Congress asked financial regulators to implement nearly 300 provisions in this law and, in so doing, translate broad policy ideas into concrete rules and regulations. Many of these regulations were vehemently opposed by financial institutions, who turned to private parties to advocate in favor of their interests. These advocates participated in thousands of meetings held between Federal Reserve Bank (FRB) members related to the Dodd-Frank law, and later these institutions and their opponents would submit tens of thousands of comment letters contesting the regulatory choices made. These records give a rare window into the world of regulatory lobbying as distinct from the more traditional lobbying sector as revealed through lobby disclosure act reports.

Undisclosed lobbying and influence seeking

In new research, by the two of us (Libgober and Carpenter), we examine what the lobbying literature misses when it takes lobbying reports at face value and fails to consider, in particular, the important influence-seeking activity of lawyers engaging in undisclosed lobbying work that targets regulators and regulation. We unearth a vast, consequential world of influence-seeking that exists beyond the scope of the existing disclosure regime. We do so by using a wide variety of empirical sources, and perhaps most critically a database of some 905 Dodd-Frank meeting logs hand-matched to regulatory dockets featuring some 6,155 private individuals discussing the implementation of these policies. Fewer than one in six of these individuals was registered as a lobbyist.

An illustration of the kind of influential lobbyist seldom seen but often felt in the regulatory process is corporate lawyer H. Rodgin Cohen. Cohen attended dozens of those meetings with the Federal Reserve about implementing the Dodd-Frank act. Cohen has been a major player in regulatory advocacy ever since the 1990s and early 2000s when he acquired connections within Bank Holding Companies (BHCs) by facilitating the then-current wave of mergers of banks. Later, during the financial crisis, he directly appealed for governmental aid on behalf of companies that he represented. However, at no point since the 2007-8 financial crisis has Cohen been registered formally as a lobbyist. We do not believe that he has skirted either the minimum activity requirements or the minimum expenditure requirements imposed by the Lobbying Disclosure Act, and we presume that he has complied with lobbying regulations. We speculate that he has relied on the exemptions in the Lobbying Disclosure Act for many of the most important categories of regulatory influence-seeking, including comment letters, “communications” more broadly made in response to notices in the Federal Register, and participation in other forms of agency proceedings.

This phenomenon of engaging in agency-focused influence-seeking without legally qualifying as lobbying isn’t limited to Cohen. It’s a widespread and consistent pattern among large financial institutions and some of the most powerful and profitable law firms on the planet. Given that these policy advocates don’t appear in most official lobbying records, their presence remains mostly unaccounted for in most scholarly literature. The result is the systematic under-documentation of critical, institutionalized, and expensive patterns that make up modern policy lobbying.

Lawyers as lobbyists

One way of looking at how much lobbying is missed by the usual methods is to start with the presumption that lawyers who engage in policy-relevant work, like Cohen, are, in fact, lobbyists in the ordinary sense of the word. How many lawyer-lobbyists, like Cohen, are also registered lobbyists? ALM Legal Compass has generated a database of lawyers by scraping law firm websites. We use this database to determine that nearly 30,000 attorneys work in the areas of Policy and Government. Most of these individuals are partners, not associates, and policy and government work seem to be something that lawyers only get into in a big way when they reach a certain professional stature. These numbers are just an annual snapshot. That said, they dwarf the existing number of reported lobbyists. In 2017, for example, the Center for Responsive Politics identified 11,611 individual lobbyists. There is relatively little overlap in these two lists of individuals, as the Cohen example illustrates. Of course, both lists likely represent undercounts because lobbyists sometimes seek to avoid having to file these reports, and we know that there are firms which appear in meeting logs at the Federal Reserve that do not appear in our database of policy and government-focused attorneys. Even just looking at the Dodd Frank Act, there were thousands more individuals who met with one agency about its rulemaking under the act than lobbied Congress about the bill, and that fails to include five other agencies involved.

“Maryland State House – Lobbying” (CC BY 2.0) by DHuiz

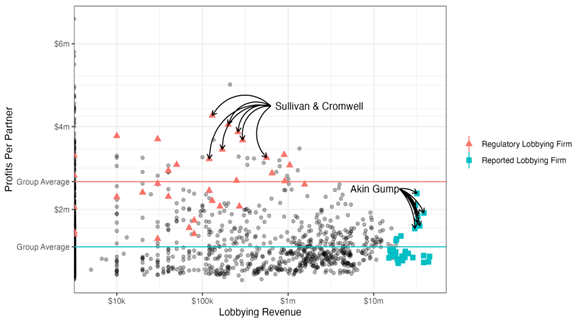

Not only are the lawyer lobbyists who work at large firms more numerous than we have conventionally and through our laws defined as lobbyists, but it is quite likely that they are more prosperous as well, overall. The American Lawyer magazine ranks firms by earnings and has done so for many decades. Crucially, many of the top reported lobbying firms in the United States are law firms, and so it is possible to use these data to compare the relative positions of major reported lobbying firms and those firms that tend to appear extensively in meetings with financial regulators. Figure 1 plots all Am Law 200 firms between 2010 and 2017, comparing the profits per partner with reported lobbying earnings from all firm years. The figure confirms the differences in profitability between regulatory lobbying firms and reported lobbying firms. Firms reporting the highest earnings from lobbying are not particularly profitable, with the partners earning only $1.1 million per year ($100,000 less than the average partner from all Am Law 200 firms). On the other hand, partners in firms involved in regulatory lobbying earned on average $2.6 million during the same period.

Figure 1 – Lobbying Revenues and profits per partner in the American Lawyer magazine’s Top 200 Firms (2010-2017)

How much is regulatory lobbying worth?

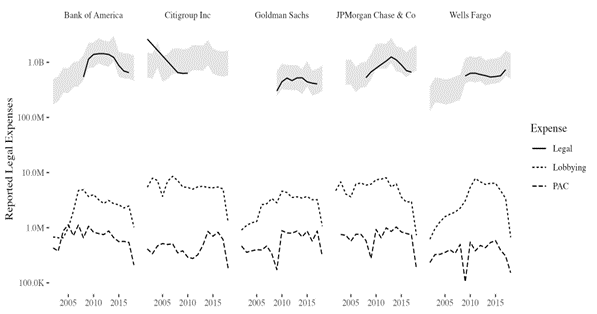

If the highest and best paid policy advocates are largely hidden from our existing reporting regime, then we must ask how much money there is in regulatory advocacy. To attempt this very difficult exercise, we rely on extensive financial reporting that banks are subject to, through their quarterly FR Y-9C “call” reports. Figure 2 shows the aggregate level of expenditure for legal expenses, lobbying, and PACs for five major Bank Holding Companies (BHCs) over different periods of the last 20 years. In any given year, legal expenses for banks are generally 100 times greater than their reported lobbying and a thousand times greater than their PAC election expenses. Of course, most legal expenditures are not related to regulatory advocacy. However, even if the fraction of legal expenses spent on regulatory advocacy was less than one percent, it would represent a comparatively significant amount of money in politics. Using a dataset of all BHCs and their legal expenses and ANOVA, we estimated that the annual legal expenditure associated with regulatory advocacy between 2010-17 could be between 0.9 and 4.6 percent. This produced a “spending explained” estimate of $458 million per year from Dodd-Frank’s enactment to 2018. This is as much as 20 times reported lobbying expenses by (roughly) the same set of firms.

Figure 2 – Legal, reported lobbying, and PAC spending for five leading BHCs

We think these findings show dramatically the extent of misunderstanding that can result from taking reported lobbying at face value and failing to account for these unreported activities. There are many categories of unreported activity, but particularly the lobbying that targets the administrative state and regulatory actors is extremely consequential.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Lawyers as Lobbyists: Regulatory Advocacy in American Finance’ in Perspectives on Politics.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-dIB