In the past two decades the voting patterns of rural and urban voters have increasingly diverged, with those in America’s cities tending to prefer Democratic candidates, and those in rural areas increasingly opting for Republicans. In new research using a large sample, Trevor E. Brown, Gisela Pedroza Jauregui, Suzanne Mettler, and Marissa Rivera look at whether people of color are also part of the rural-urban political divide. They find no significant or meaningful difference in voting behavior between rural and urban Black or Latino respondents. They also find few differences in policy preferences between racial and ethnic groups in rural areas and between urban and rural areas.

In the past two decades the voting patterns of rural and urban voters have increasingly diverged, with those in America’s cities tending to prefer Democratic candidates, and those in rural areas increasingly opting for Republicans. In new research using a large sample, Trevor E. Brown, Gisela Pedroza Jauregui, Suzanne Mettler, and Marissa Rivera look at whether people of color are also part of the rural-urban political divide. They find no significant or meaningful difference in voting behavior between rural and urban Black or Latino respondents. They also find few differences in policy preferences between racial and ethnic groups in rural areas and between urban and rural areas.

In recent decades, a new political divide has emerged and roiled American politics, pitting those who live in sparsely populated areas against those in dense urban ones. As shown in Figure 1, in the early 1990s, voters in rural and urban counties nationwide voted similarly to each other in presidential elections. Since 2000, however, rural voters have increasingly voted for Republican presidential candidates, while Democratic support has boomed in large cities and grown in small cities and suburbs. This rural-urban divide has manifest across all regions of the nation and become a major source of social polarization, creating “us” vs. “them” dynamics.

Figure 1 – The Emergence of the Rural-Urban Divide in Presidential Voting

Political scientists who study American politics have begun to describe this relatively new division in rich detail. Drawing on both ethnographic research and analyzing surveys with large sample sizes, scholars have provided evidence of rural people’s resentment toward urbanites; rural dwellers’ support for the Republican Party; and how rural residence and “rural consciousness” are associated with anti-Black racism and other forms of prejudice, particularly among non-Hispanic whites. Elsewhere, two of us have offered a historical explanation for the divide—one that stresses the interaction between place-based economic inequality, the development of the American state, and the organizational landscape of rural areas.

While empirically and theoretically valuable, existing research has yet to directly examine whether such a divide exists among people of color. Using data from the US Census Bureau, Figures 2 and 3 show that people of color—particularly Latinos—make up a growing and substantial share of the rural population. As of 2020, one in four people living in rural areas is a person of color. This begs the question: Have people of color been swept up into the rural-urban political divide?

Figure 2 – Share of Population Identifying as Nonwhite by Place, Over Time

Figure 3 – Share of Population Identifying as Latino by Place, Over Time

Voting behavior across race, ethnicity, and place

In new research, we begin to answer this question by drawing on survey data from the Cooperative Election Study (CES, formerly the Cooperative Congressional Election Study). Due to survey data limitations, we focus on self-identifying Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white respondents. We code whether their county of residence was rural or urban according to a widely used measure produced by the US Office of Management and Budget. To generate a reliable sample, we combine respondents across all four presidential elections from 2008 to 2020, offering us several thousand respondents for each racial and ethnic group. Figure 4 shows the descriptive results.

Figure 4 – Party Vote Choice by Race, Ethnicity, and Place

As Figure 4 shows, the only meaningful difference in voting behavior across place is among non-Hispanic whites. Compared to their urban counterparts, rural white people have been more supportive of Republican candidates by roughly 11 percentage points. Meanwhile, we do not detect a statistically significant or meaningful difference in voting behavior between rural and urban Black or Latino respondents (“Hispanic” was the self-identified ethnicity option given in the CES survey. We refer to these respondents as “Latino” throughout this post).

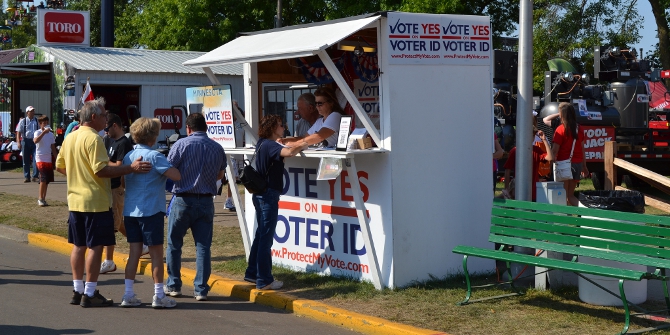

Photo by Shelby Cohron on Unsplash

Different groups’ policy preferences

What about public policy preferences? Even if rural Black and Latino respondents continue to vote for Democrats at similar rates across place, this could mask important differences when it comes to how they feel about important policy issues.

To examine this possibility, we turn to responses from the Cooperative Election Studies’ (CES) Public Policy Data Set. We examined more than 30 questions across several policy domains, probing attitudes on key issues such as taxes and spending, trade, gun regulation, access to abortion, and LGBTQ rights, among others. (Our full results can be found here, as well as information on how the questions were phrased and how we coded responses.)

Strikingly, we only found very few gaps worthy of note—among all racial and ethnic groups—across rurality. To be sure, some differences did emerge, such as attitudes toward legalizing gay marriage and access to abortion. Yet when they did show up, the differences between rural and urban voters were relatively modest, ranging from just two to 12 percentage points. After accounting for other important factors, such as age, education, and gender, in our analyses, these gaps often became even smaller. While the primary goal of our research was to explore differences in rural and urban voting across racial and ethnic groups, an important secondary finding is that preferences on public policy—especially hot-button, so-called “culture war” issues—are a poor explanation for the rural-urban political divide, even among non-Hispanic whites.

The need to further study race, ethnicity, and place

Despite being similarly exposed to economic deterioration and neglect from the Democratic Party, why have rural Black and Latino Americans not shifted to the Republican Party alongside their white peers? Given the limitations of the data we use, we can only conclude by speculating and drawing on theories from scholars of racial and ethnic politics. Beginning with Michael Dawson’s path-breaking research, political scientists have found that varying degrees of “linked fate”—the belief that one’s individual fate is tied to that of their racial or ethnic group—can help explain why Black and Latino Americans do not diverge across other social axes, such as socioeconomic status. Political scientists Ismail White and Chyrl Laird also offer a theory of “racialized social constraint,” whereby Black Americans who hold more conservative views follow social pressures to continue supporting the Democratic Party. It is also possible that the rhetoric of many Republican elected officials and candidates may simply be alienating rural Black and Latino Americans. Untangling the mechanisms that hold the voting behavior of rural and urban Black and Latino Americans together is a crucial avenue for future research.

Beyond pinning down those dynamics, we urge scholars to conduct more research on rural people of color more broadly. Studying other racially marginalized groups, beyond Black and Latino people, is key. As our on-going research shows, such groups receive little attention from the two major political parties and are often not adequately represented in politics. Conducting such research will require significant investment, including large oversampling of rural people of color in survey analyses as well as “on-the-ground” field work. But doing so is vital for a fuller understanding of the politics of place and the health of American democracy.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘A rural-urban political divide among whom? Race, ethnicity, and political behavior across place’ in Politics, Groups, and Identities.

- Please read our comments policy before commenting.

- Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-dXk