In traditional political economy theory, voters who have been hurt by economic crises should demand more social protection and greater income redistribution. However, this is not what has happened after the latest financial crises. Giray Gozgor analyses what the theory tells us about the rise of right-wing populism.

In traditional political economy theory, voters who have been hurt by economic crises should demand more social protection and greater income redistribution. However, this is not what has happened after the latest financial crises. Giray Gozgor analyses what the theory tells us about the rise of right-wing populism.

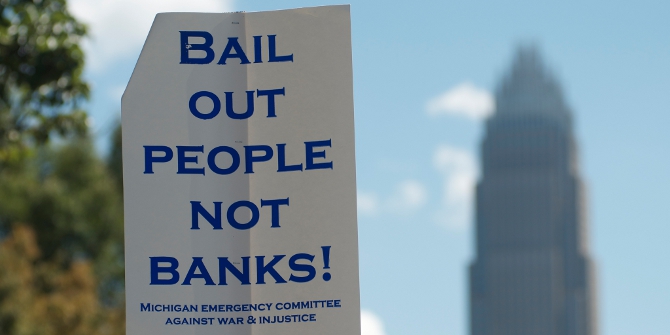

Economic downturns also trigger social controversy because voters believe that the ruling elites responsible for the crises are not suffering the consequences. Populist politicians argue that financial sector managers and corporate shareowners profit during prosperous times, while taxpayers finance bailouts for crisis-related losses.

Western Europe has seen a surge in populist movements, previously more prominent in central and eastern European countries. This is evident in the rise of far-right parties like France’s National Rally, Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland, the Sweden Democrats and Reform UK, along with the electoral gains of the far-right movement in Italy.

Economic interests are assumed to be the leading driver of political preferences. In traditional political economy theory, voters who have been adversely affected by economic downturns should demand more social protection and an increase in income redistribution. However, the economic downturns caused a significant increase in support for populist parties.

Definitions

Scholars have defined populism as a “nationalist,” “anti-immigrant,” and “anti-elite” political ideology based on voters’ optimal responses to rising income inequality. They see populism as a political “style”, rather than a set of policy proposals. Populist politicians claim to represent the “true people” against “corrupt elites” and to adhere to the concept of the “will of the people” rather than the “will of the voters”. In other words, populists refer to “the people” as singular. That definition implies not only that anti-immigration policy proposals are populist but also that populism has a broader appeal.

Liberal institutions are viewed as obstacles to the will of the people, so populists tend to favour the more active implementation of simple majority rule. Their political viewpoint claims to represent the “people’s common interests”, which is defined differently, depending on ideology. For those from the right wing, the people’s common interests include opposition to minorities and foreigners, while left-wing populists oppose the interests of financial elites.

What do theories tell us?

Four main theoretical approaches have been taken to explain voting behaviour in terms of significant economic uncertainty shocks.

- The “economic insecurity hypothesis” holds that people will vote for leftist parties in times of economic uncertainty. Since they demand more income redistribution and more social expenditures.

- Voters who have experienced a significant economic uncertainty shock are less interested in politics and prefer to abstain.

- Voters who have experienced a significant economic shock are pragmatic and will vote against the ruling party, regardless of their political opinions.

- In times of economic downturn, electorates will be eager to vote for populist candidates and political parties. The evolutionary psychology literature shows that humans tend to organise around a dominant leader, especially in situations of environmental uncertainty or threat.

Economic uncertainty shocks

The final theoretical conjecture implies that people will vote for right-wing populist parties because of their anti-establishment rhetoric, punishing corrupt elites. They will demand reductions in the rights and financial resources of immigrants and minorities and, in contrast to the economic insecurity hypothesis, they argue that economic crises will cause populist movements to be promoted over leftist ones.

Such an outcome is anticipated because voters want to punish the establishment when the economy slows and household debt rises. They also tend to blame globalisation and immigrants as unemployment rates rise and will vote for populist movements or leaders who support anti-globalisation and nationalism, particularly in times of economic distress.

Economic uncertainty may be the driving factor behind the rise of populism in Europe, with its anti-immigrant sentiments, triggered by individual economic concerns. At this stage, economic uncertainty shocks may help explain the vote for populist parties. The existing literature suggests that major macroeconomic events and financial crises, such as the great depression of the 1930-1940s and the 2008–9 global financial crisis, have significantly affected people’s views on political parties and their voting behaviour.

Economic downturns also trigger social controversy because voters believe that the ruling elites responsible for the crises are not suffering the consequences. Populist politicians argue that financial sector managers and corporate shareowners profit during prosperous times, while taxpayers finance bailouts for crisis-related losses.

The 2008–9 crisis also strengthened support for the popular view that ruling elites protect their interests during such crises, while losses are borne by the “common people”. Using data from 1870 to 2014, a study investigated the political consequences of economic crises and found that they typically lead to stronger political support for extreme right-wing parties. These effects were more significant empirically in central and eastern Europe during the post-2008–9 financial crisis than in other countries, especially Western European ones.

Voting under economic uncertainty

Contradicting the economic insecurity hypothesis, economic crises will cause populist movements to be promoted over leftist ones. This outcome is anticipated because voters want to punish the establishment when the economy slows and household debt rises. The rising cost of living, mortgage debts, student loan debts, and unstable job markets can make people feel like the system is not working for them.

Voters also tend to blame globalisation and immigrants if unemployment rates rise. People who feel economically insecure might be more receptive to messages from the extreme right that scapegoat immigrants or minorities for their problems. Previous findings have also shown how some people think that strong leadership can solve the problems related to economic downturns, which the extreme right often promises.

Conclusion

Economic uncertainty boosts support for populist parties. Populist politicians also emphasise greater economic uncertainty, especially in the wake of the 2008–9 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic in the early 2020s.

Other economic factors beyond uncertainty help to explain the trends in populist politics. As exemplified by the case of France’s National Front (FN), many right-wing populist parties underwent a programmatic shift during the 1980–2020 period, that is, from traditional right-wing positions of limited state intervention to positions favouring the expansion of welfare benefits. That shift occurred in response to changes in the social base of these parties, with increasing numbers of working-class and low-skilled workers in precarious jobs.

Established parties (especially those on the right, like the Conservatives) may have shifted their positions to the right in recent years. This shift could be a response to the growing popularity of ideas associated with populism, particularly those concerning immigration. Finally, populist policies are not limited to populist parties and can involve mainstream ones too. The political characteristics of events are more important than the classification of political parties. The effects of geopolitical risks and COVID-19-related shocks on populist voting behaviour should also be considerable. And little evidence has been reported in the empirical literature on the impact of economic uncertainty shocks on voter turnout rates.

- This blog post is based on The role of economic uncertainty in the rise of EU populism, in Public Choice and first appeared at LSE Business Review.

- Featured image provided by Shutterstock

- Please read our comments policy before commenting

- Note: The post gives the views of its author, not of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

- Shortened URL for this post: https://wp.me/p3I2YF-e6P