The concept of “patriarchy” has been both a call to action and an analytical tool for feminist understandings of women’s place in the world as we know it. Over the past 100 years, feminist activists have made signs, worn on their chests, or loudly exclaimed the mantra: “smash the patriarchy”. In this article Cassandra Mudgway presents analysis on how patriarchy is used in international law and by treaty monitoring bodies, cautioning against limiting the scope and meaning of patriarchy by only associating it with some beliefs and practices and not also seeing it as a system of power.

As an academic term, “patriarchy” has been challenged, re-defined, re-examined, rejected and rediscovered. The concept of patriarchy has proven to be elastic and has earned a central place within feminist scholarship. Within this scholarship, there are two general interpretations of patriarchy. First, patriarchy as the overt subordination of women by men. This oppression is conceived as a feature of society and culturally constructed. Second, patriarchy as a system of power which is hierarchical and autonomous, permeating every facet of society. This interpretation has been expressed by feminist author bell hooks in the following way:

Patriarchy is a political-social system that insists that males are inherently dominating, superior to everything and everyone deemed weak, especially females, and endowed with the right to dominate and rule over the weak and to maintain that dominance through various forms of psychological terrorism and violence

In 1981 the international Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) came into force, with 189 states now signed onto the treaty. Those 189 states agreed to protect and ensure women’s human rights and endeavour to take all reasonable steps to guarantee gender equality. Additionally, states agreed to dismantle social, religious and cultural structures which foster the subordination of women by men. Taking the meaning of patriarchy as a system of power as expressed by bell hooks, this would seem to suggest that CEDAW requires states to dismantle patriarchal structures and attitudes, from the government to the private sphere.

However, the treaty itself does not mention the word patriarchy. Despite the absence of the word from the text of the Convention, it is possible that the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Committee) is using the concept of patriarchy when applying the Convention to state practice.

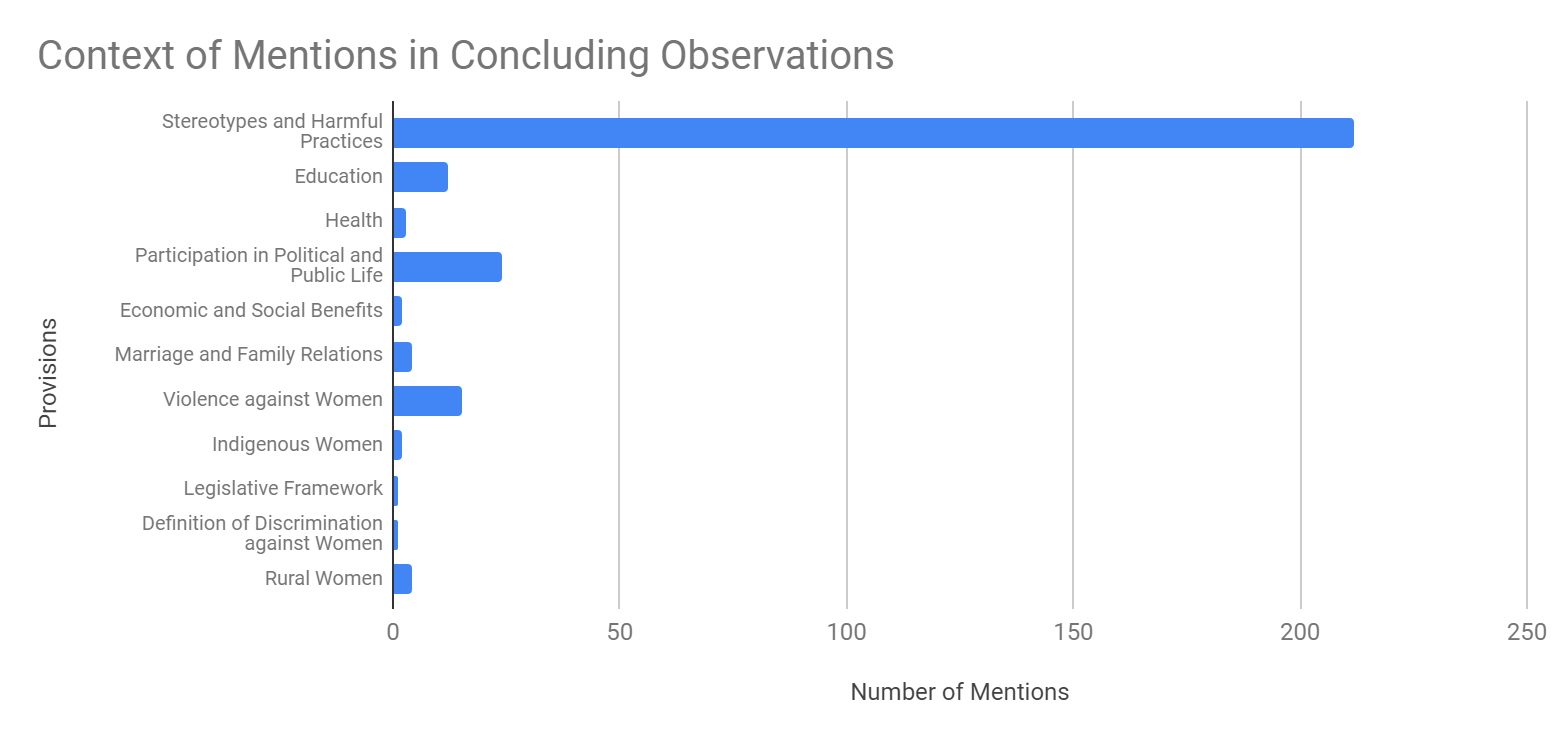

By interrogating this possibility and investigating the meaning given to patriarchy as utilised by the CEDAW Committee we can see that they do use the concept of patriarchy when interpreting state obligations under the Convention and that patriarchy is used almost exclusively in connection with article 5(a). This article is one of the most important provisions in the Convention. Article 5(a) is about eliminating harmful gender stereotypes generally. It speaks of modifying social and cultural practices which reinforce negative gender stereotypes about the roles of women in public or private spaces.

The CEDAW Committee considers “social and cultural patterns of conduct” to include religious, traditional and customary beliefs, ideas, rules and practices. However, “patriarchy” is only explicitly utilised in the concluding observations of some states parties but not in others, reinforcing the problematic distinction between non-western and non-European states versus western and European states.

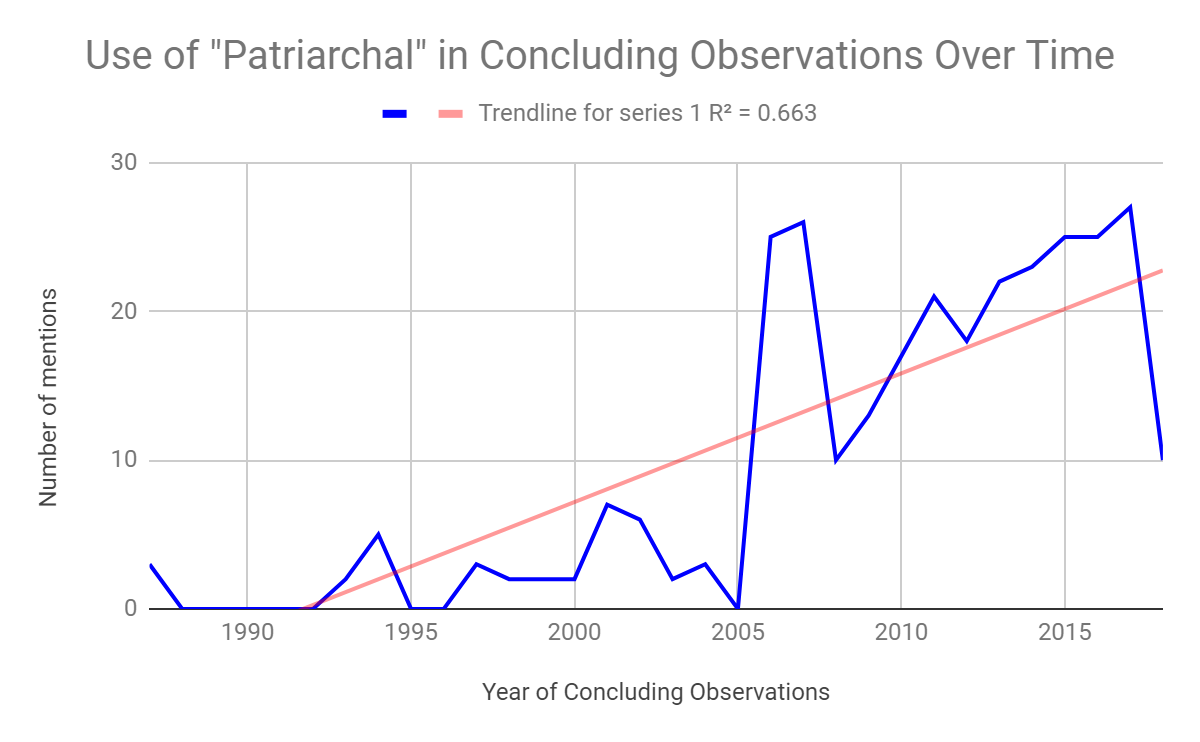

A total of 656 concluding observations, dating from 1987-2018, were searched for the words “patriarchy” and “patriarchal”. Collectively, these terms were located in 289 concluding observations. Within these documents, the word “patriarchy” was found only three times whereas the word “patriarchal” was found 299 times. Each instance of either “patriarchy” or “patriarchal” was recorded alongside (a) the year of the concluding observation, (b) the article(s) under the Convention which was being discussed when the term was mentioned, and (c) the state party being observed. From this analysis the following trends were identified.

Increased use of “patriarchy” and “patriarchal” over time

Since 2006, the CEDAW Committee has consistently and purposefully used “patriarchy” and “patriarchal” in its concluding observations. The noticeable spike in 2006 and 2007 indicates that the terms are being used intentionally. For example, in 2005 the Committee did not refer to “patriarchy” or “patriarchal” at all. However, in 2006 these terms were used 25 times in concluding observations and an upwards trend has been maintained since. Therefore, it can be argued that such a dramatic increase was the result of an intentional choice to use the terms. Additionally, this increased use may suggest that the particular composition of the CEDAW Committee at that time introduced the word into concluding observations.

Patriarchy in Connection with Article 5(a)

In 75.7 per cent of the concluding observations searched, “patriarchy” and “patriarchal” were used in reference to “stereotypes and harmful practices”: this relates to article 5 of the Convention. Moreover, despite a few rare instances, mentions of “patriarchal” and “patriarchy” are primarily associated with article 5(a).

The most common usage of “patriarchal” in these concluding observations was in the following way: “[The CEDAW Committee] is concerned at the persistence of patriarchal attitudes and deeply-rooted stereotypes regarding the roles and responsibilities of women in the family and in society” (as used in the concluding observations of Pakistan. Similar examples include Syria, Kyrgyzstan, Cameroon, Uganda, and Marshall Islands).

Article 5(a) obligates states to eliminate negative gender stereotypes which foster discrimination against women. This article is an important pillar to the Convention itself because it implies structural change is necessary, rather than simply altering the law. Additionally, “patriarchal” is used alongside “harmful traditional practices”. Although examples differ depending on the state under observation, harmful traditional practice is used in reference to some of the following: FGM, so-called honour killings, sexual initiation practices, abduction of girls, early and forced marriage, polygamy, widow inheritance, son preference, and violence against women generally.

Western and European States are not Patriarchal?

Of states parties which have completed concluding observations between 1987 and 2018, I found that “patriarchy” or “patriarchal” are mentioned in approximately 81 per cent of them, meaning the majority of states parties have had the term used in their observations. However, when examining the states parties with the most mentions of “patriarchy” or “patriarchal”, certain groups of states are over-represented: these include Middle Eastern and Central Asian states, such as Pakistan, Syria, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Qatar, Iraq and Nepal.

However, 32 states parties have never mentioned “patriarchy” or “patriarchal” .Western and European states (i.e. states which are in Europe and states whose current population predominately derived from Europe during the era of European colonialism) are over-represented in this group and even more so when comparing with the total number of completed concluding observations made on those states between 1987 and 2018. Of those states which have had three or more completed observations and yet have never had the term “patriarchy” or “patriarchal” used, 74 per cent of those states are western or European states, these include Norway, Denmark, Luxembourg, Austria, Germany, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

The Concept of Patriarchy as used by the CEDAW Committee: Implications

Conflating “patriarchal attitudes” with “harmful traditional practices” means that patriarchy is being interpreted in a specific way: my analysis of the CEDAW Committee statements suggests that patriarchy is associated with so-called traditional beliefs or practices including, amongst other things, FGM, sexual initiation practices, early and forced marriage, polygamy, son preference, and violence against women. It could be argued that these practices are being utilised as direct indicators of patriarchy. After all, these practices are incredibly harmful to women and are overt examples of oppression.

However, just because there is a general absence of these more direct or coercive manifestations of oppressing women, arguably does not render “patriarchal attitudes” absent. In fact, by avoiding using “patriarchal attitudes” in some concluding observations but not in others, the CEDAW Committee are painting a limiting picture of what a “patriarchal” state looks like. For the purposes of interpreting obligations under the Convention, the CEDAW Committee does not appear to be utilising the concept of “patriarchy” as a system of power. The meaning of patriarchy as utilised by the Committee aligns itself with the limited interpretation as the overt subordination of women by men. Limiting patriarchy to mean culture and “harmful traditional practices” in this way risks othering and exotifying patriarchy itself. This usage of patriarchy is also a far cry from the meaning as conceptualised by some notable feminist theorists and activists, such as bell hooks.

This piece is part of a wider project investigating how the concept of “patriarchy” is used in international law. This project continues to interrogate the use of “patriarchy” among treaty monitoring bodies of the remaining seven core international human rights instruments including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and the Convention against Torture. A comparative analysis will be completed by the end of 2019.

Header Image: Pedro Ribeiro Simões (CC BY 4.0)

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.