National Action Plans (NAPs) are a strategic tool for states to translate the international mandates of the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda into the domestic context. As of August 2019, 42% of UN member states – or a total of 82 countries – had released at least one NAP. Caitlin Hamilton, Nyibeny Naam, and Laura J. Shepherd recently put together a dataset of all available NAPs and analysed them to identify various trends in NAPs worldwide, which they published in a report. In this blog post, they present some of the highlights from their analysis.

Dominant pillar(s)

One of the things that we looked at was which pillar(s) of the NAPs are dominant, and if this is changing over time. Here, we found that the participation pillar proved the most influential over time, though there is growth on the prevention pillar, particularly in recent years. This could represent an increased desire to prevent conflict in the first place, or – and possibly more likely given that WPS resolutions focusing on sexual violence in conflict (SVIC) were adopted in 2009 – it could relate to the prevention of SVIC. Protection has been an ongoing pillar across time, but recent times have seen fewer NAPs take protection as their dominant pillar, seemingly skewing instead towards participation. The notion of protection, as Björkdahl and Selimovic explain, exposes the “unresolved tensions between ‘protection’, ‘representation’, and ‘participation’ in UNSCR 1325 agenda”, and as a concept, ‘protection’ may not have the same appeal or potential as a transformative pillar of WPS as do participation and prevention.

Lead agency

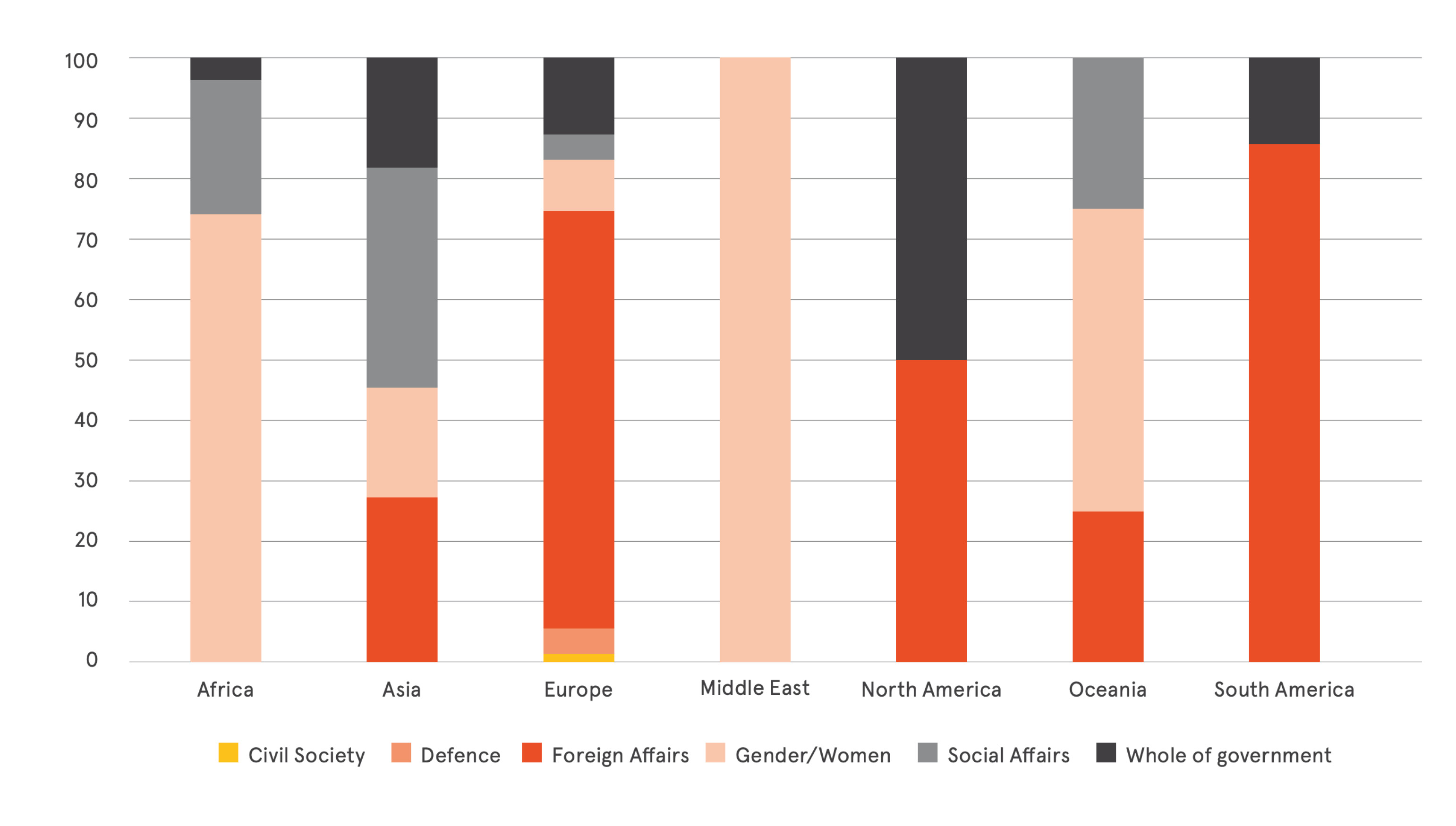

We also considered the location of the NAP in the machinery of government (in other words, which ministry or department is the ‘lead agency’), both over time and by region. States tend to see the WPS agenda as either a matter for Foreign Affairs or departments that have a focus on gender or women. Both of these placements may be problematic.

Locating the NAP in Foreign Affairs can result in outward-facing NAPs, which see WPS as an agenda which addresses problems that occur ‘elsewhere’, such as in the global South. This outward orientation positions WPS as a matter of foreign policy, aimed at (usually conflict-affected) areas outside of the territory of the authoring state. Consequently, these NAPs tend to conceive of WPS in narrow militarised terms, often focusing on the number of women within the armed forces. These NAPs also tend to ignore the role(s) that the authoring states may play in fuelling conflict or insecurity beyond their own borders – including through the sale of arms and flows of funds.

Equally, placing a NAP under the auspices of a Ministry of Women’s Affairs, for example, frames the WPS agenda as a ‘women’s problem’, with the limited attention and funding that you might expect from such framing.

Locating the NAP in Foreign Affairs can result in outward-facing NAPs. This outward orientation positions WPS as a matter of foreign policy, aimed at (usually conflict-affected) areas outside of the territory of the authoring state. Consequently, these NAPs tend to conceive of WPS in narrow militarised terms, often focusing on the number of women within the armed forces

When we organised these data by region, however, we were struck by the differences in category of lead. NAPs coming out of countries in Africa and the Middle East, and to a large extent Oceania, account for the vast majority of Gender/Women NAP leads, whereas NAPs from Europe, North America and South America are overwhelmingly more likely to have Foreign Affairs as a lead agency or to take a whole-of-government approach.

Category of NAP lead by region (n=128)

This whole-of-government approach is preferable for many reasons, not least in its recognition that the meaningful implementation of the Agenda requires comprehensive and sustained support from a range of actors in a variety of sectors.

Emerging security issues

We then explored the extent to which new or emerging security issues (like terrorism, climate change and reproductive rights) are represented in the NAPs. We found that NAPs often incorporate a diverse range of issues that extend beyond traditional security concerns. These are sometimes drawn from the Security Council resolutions, and sometimes reflect the context and interests of states and other implementing actors. Trafficking, for example, is prominent in the three NAPs produced by Bosnia and Herzegovina, while transitional justice is a recurring theme in the Solomon Islands’ NAP and terrorism is a primary focus in Jordan’s NAP.

On one hand, this is a sign that states are considering their local context when developing their NAPs, which is absolutely vital for a NAP to be relevant and meaningful to a state’s population. It also reflects the fact that war affects people’s lives in many different ways, and that a peace and security agenda needs to recognise and address these issues. On the other hand, however, some states have expressed a reluctance to expand the Agenda beyond some of the more traditional ‘war and peace’ topics. It can also create a greater burden on civil society groups who are often already un(der)funded and operating with extremely limited resources.

Trafficking, for example, is prominent in the three NAPs produced by Bosnia and Herzegovina, while transitional justice is a recurring theme in the Solomon Islands’ NAP and terrorism is a primary focus in Jordan’s NAP

Lack of funding

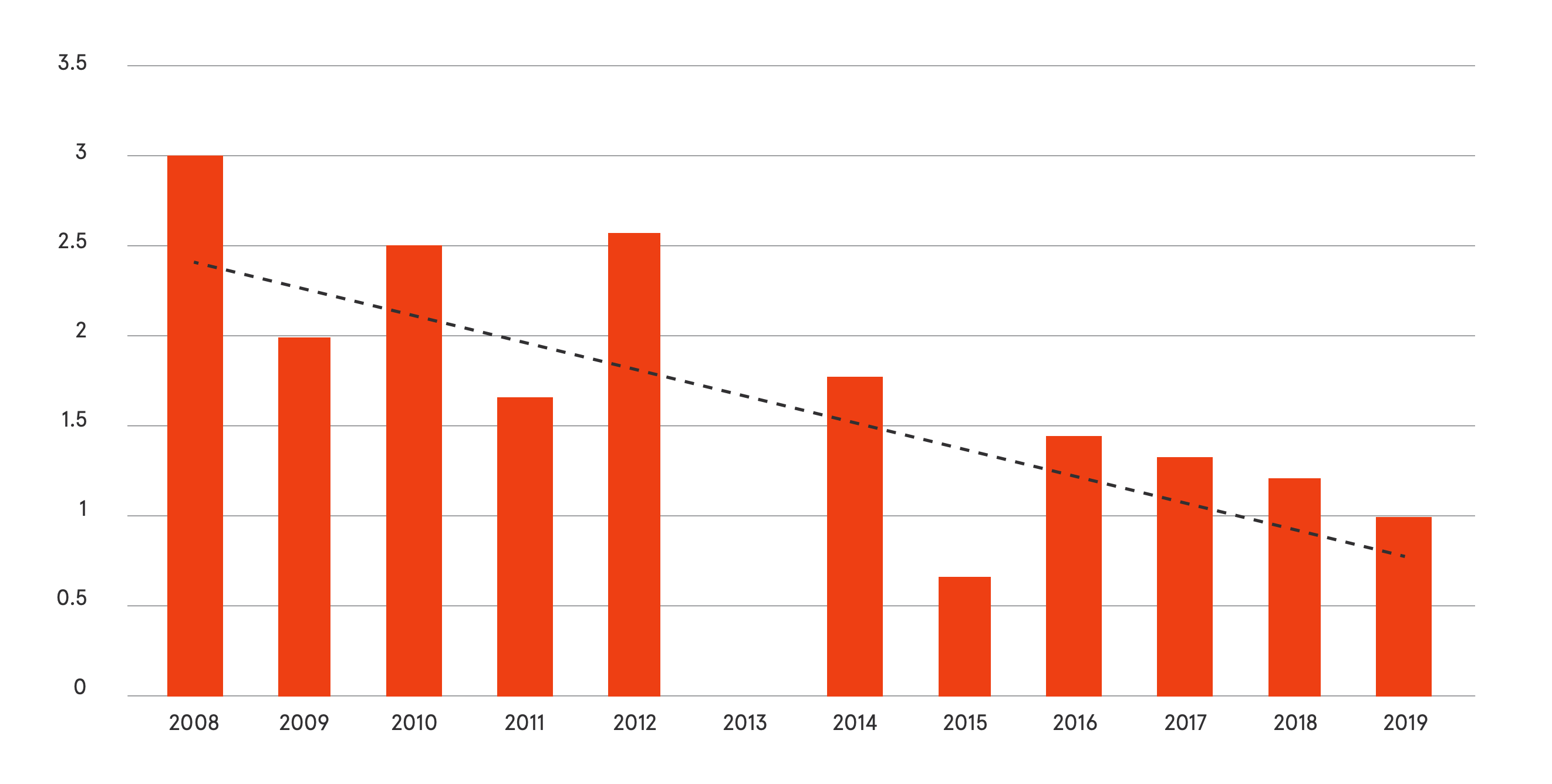

This lack of sustainable funding is a major obstacle to the implementation of the WPS agenda. For a NAP to be effective, it requires a specific budget allocation for WPS activities, a ‘predictable and sustainable financing’ source, and proper management and tracking of funds. As it stands, however, a large percentage of NAPs fail to allocate a specific budget for WPS activities. We found that most budgets either have no or very little specification of how the NAP-producing country intends to fund their NAP activities. And it seems to be getting worse; when we studied the current NAPs (which we defined as the NAP of a country that had only one NAP, or the latest NAP if a country had multiple iterations), we found a clear downward trend, which is particularly apparent in NAPs adopted since 2014.

Average level of budget specification in current NAPs (n=81)

Monitoring and Evaluation Frameworks

In addition to sufficient and reliable funding, effective NAPs need to have robust and clearly defined monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks. Monitoring and evaluation frameworks are important for a number of reasons. They:

- allow states and stakeholders to be clear about their goals, timeframes, resources and indicators

- create consensus on how to evaluate the progress, impact, and implementation of a given WPS initiative in a state or region, and

- reduce policy incoherence and duplication.

Unlike funding, we found that the M&E specification across all NAPs was generally reasonable – the majority of NAPs clearly specified goals and responsible parties. The strongest NAPs were also really specific about the timeframes in which the WPS-related activities would take place and about the indicators for the goals.

Civil society Involvement

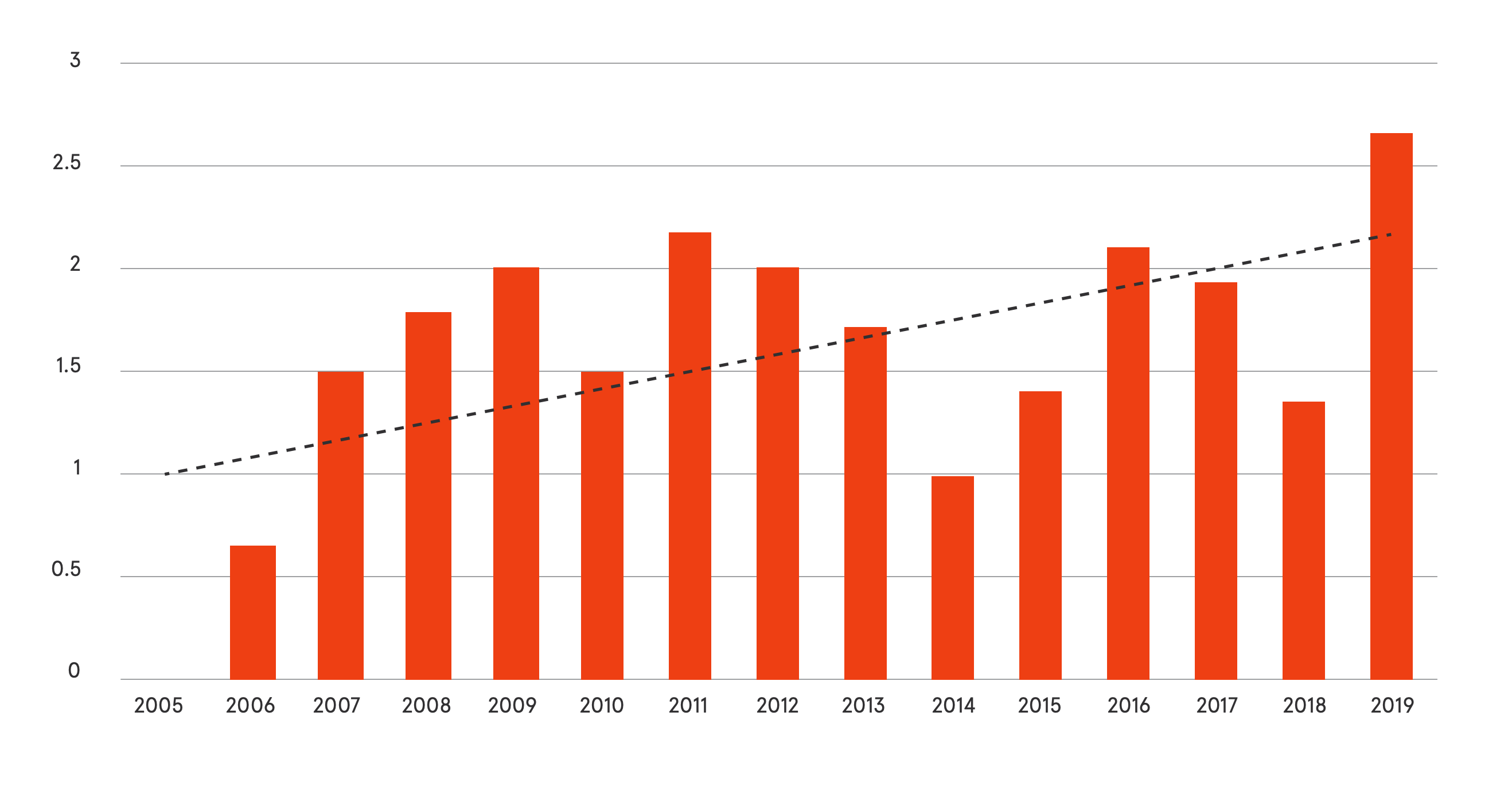

Last but not least, coordination with civil society organisations (CSOs) is an important aspect of an effective NAP. Ideally, CSOs are seen “as an equal partner to its governmental counterparts in all stages”. One benefit of including CSOs in a meaningful way in the process of NAP development and implementation is that it can promote the inclusion of women and girls in decision-making around peace and security – which is a central ethos of UNSCR 1325.

Given that participation is a central pillar of WPS, it is important that inclusivity is built into the development of NAPs and the implementation of the WPS agenda. This means not only consulting civil society in developing and implementing NAPs but consulting widely with civil society (such as in rural or regional areas as well as in cities) to make sure that challenges to peace and security experienced by specific populations are recognised and incorporated.

We identified some degree of engagement with civil society in the development of the NAPs, but there is scope for more clearly defined and substantive input. Very few NAPs, for example, name civil society as a co-drafter along with the state (with the Netherlands’ third National Action Plan being one exception). Most NAPs, however, either have limited or no clear engagement with civil society at all. However, the level of engagement with civil society is increasing over time, which we are taking as a promising sign of the NAPs to come.

Given that participation is a central pillar of WPS, it is important that inclusivity is built into the development of NAPs and the implementation of the WPS agenda. This means not only consulting civil society in developing and implementing NAPs but consulting widely with civil society to make sure that challenges to peace and security experienced by specific populations are recognised and incorporated

Average level of engagement with civil society in NAPs over time (n=128)

It takes a lot of work to produce a NAP – to identify, negotiate and express a variety of priorities, responsibilities, funding imperatives, and ideas of gender, peace, and security. NAPs (perhaps inadvertently) reveal a lot about countries: which relationships they see as valuable, how they see their place in the world, and what they perceive their most pressing security issues to be. NAPs are, in short, fascinating documents.

But NAPs shouldn’t just be documents. The whole point of a NAP is that it is to be implemented: so that more women will take part in peace negotiations; so that gender-based violence is reduced, or eliminated, in conflict and post-conflict contexts; so that necessary services are funded on the ground; and, of course, so that, ultimately, conflict is prevented.

We are fast approaching the anniversary of the first twenty years of the WPS agenda. Now, more than ever, is the time for states to move from rhetoric to commitment, and from plan to implementation.

Read the full report: Twenty Years of Women, Peace and Security National Action Plans: Analysis and Lessons Learned

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.