Can some of the well-intentioned arguments for women’s participation backfire? Karolin Tuncel argues that the common narratives frequently used can actually undermine the WPS agenda’s intentions, and that working for women’s participation should also mean understanding and then unlearning the very system that discriminates against different social groups in the first place.

In October 2000, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) adopted resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) with the intention of including women and gender perspectives in the UN’s peace and security work. 20 years and nine subsequent resolutions on WPS later, it is time to assess the direction of the agenda as a political project and its conceptual future. What kind of ‘meaningful’ participation does the WPS agenda demand? And what implications does this have for international security structures such as the UNSC in which women are to participate? In order to reach a truly meaningful participation, arguments must shift their focus from women and towards changing the system that excludes them.

Almost everybody who is engaged in promoting the WPS agenda – be it diplomats, staff of peace operations or advocates in NGOs – likely agrees that every social group, including women, has the right to participate in decision making that affects them. Those advocates constantly emphasise the importance of women’s meaningful participation.

However, advocates often seem to lack an awareness of how they argue for this participation. Yet how they argue for women’s participation matters. Such arguments not only inform us about why participation is important, but they are also a crucial way of determining what participation looks like in practice, and with this, the direction of the WPS agenda. Some of the well-intentioned arguments for women’s participation can easily backfire. How? Two examples.

First, let’s take a closer look at the most frequently used argument for women’s participation in the WPS debate which links gender equality to successful peacebuilding: women bring peace. For example, as many others also do, the Council on Foreign Relations argues: ”evidence shows that peace processes overlook a strategy that could reduce conflict and advance stability: the inclusion of women.”

Demanding women’s participation because women bring peace implies two things; firstly that gaining peace is considered the primary objective of the WPS agenda (so far so good). But at the same time, such an argument uses an “add women and stir” narrative which limits women’s participation to roles in which women are expected to contribute to building peace.

This can mean for example the role of reducing the rate of sexual violence, or the role of increasing the credibility of forces. Most importantly, “women bring peace” adds a conditionality to participation claims. If we argue that women should participate because they bring peace, we imply that women’s right to participation can be taken away if they do not fulfil the condition of being more peaceful than men.

Women bring peace arguments are not the only questionable narrative in the current WPS discourse. While these often address the supposedly peaceful character of women, different perspective arguments target the content of their participation. They claim that women’s participation brings in a different perspective, and frame (often essentialised) women’s needs as a reason for why women should participate.

If we argue that women should participate because they bring peace, we imply that women’s right to participation can be taken away if they do not fulfil the condition of being more peaceful than men.

Such an argument implies, firstly, that a diversity of perspectives is considered a primary objective of the WPS agenda (again, so far so good). Secondly, however, it carries the implication that women only need to participate where they can offer a different perspective from men. Such an argument reduces women to an untapped resource of knowledge, lays the ground for limiting women’s participatory spaces to roles such as gender advisors and again, most importantly, it links the participation claim to the condition of bringing in a new perspective.

What do these two examples have in common? They follow an instrumentalist rationale, using women’s participation as an instrument – not as an end in itself – to integrate women into existing security structures. Such an instrumentalist thinking ensures women’s participation only as long as it is beneficial. It depicts women as a “key to peace”, as an instrument and reduces a gender dimension to an add-on.

Such a rationale does not only miss the objective of gender equality, it also limits the possibilities of the WPS agenda by leaving out important feminist questions such as: which issues does the international community consider to be relevant for international security? And is the international community using the right means and processes to tackle these issues?

What would be a less instrumentalist way of promoting the WPS agenda? The short answer is when arguing for participation, don’t focus on women, but focus on concrete reforms that reflect a feminist agenda.

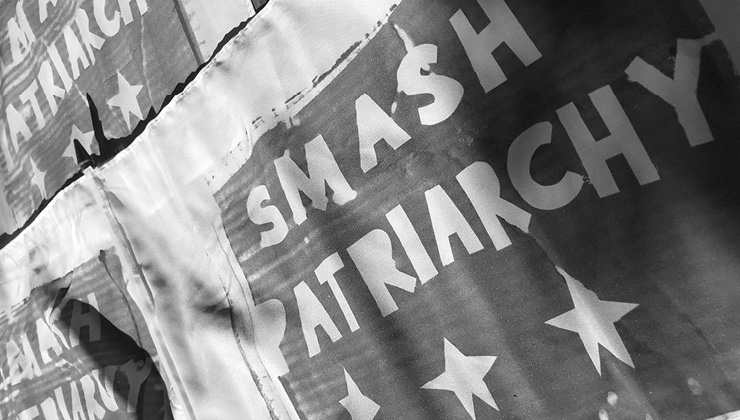

A crucial step for this is to shift the focus from women towards the existing exclusion of women and other groups. If advocates really want more diversity, a higher percentage of (mostly privileged) women in peace and security structures is not the solution. Instead, we have to put our energy into first understanding and then unlearning these structures that discriminate against different social groups. This can mean developing an intersectional quota system that also reflects the applicants’ geographical and social background, or openly sharing and discussing recruitment processes at the UN.

We have to put our energy into first understanding and then unlearning these structures that discriminate against different social groups

Secondly, considering the content of participation claims, the WPS agenda should not be reduced to an advocacy for women to ‘join the club’. Allowing a woman to do the same thing as her male predecessors won’t make peace and security structures any better. Instead, the agenda should provide a discursive space for everyone to rethink the established understandings and practices of international security. Participatory approaches to peace and security should demand participation that goes beyond the mere presence of women, e.g. by further developing non-militarist ways of participating in peacebuilding, and concepts like human security in contrast to state security.

Is such a shift towards a transformative thinking of the WPS agenda possible? Yes, but as every change, it requires not only awareness, but also the political will of advocates and allies to foster a transformative debate – also while facing actors and states that (more or less openly) oppose the WPS agenda. The message is simple: women should not be able to participate because they are thought to bring better results than men. Every social group, including women, has the unconditional right to participate in decision making that affects them.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.