Maria Tanyag writes on how anti-feminist movements have used feminist slogans and campaigns to pursue aggressive policies against women’s bodies and sexual and reproductive health and rights. To counter this, we must better understand their strategies and transnational influence, and harness this pandemic as an opportunity to collectively rebuild societies with reproductive justice as a priority.

One of the many disheartening news stories that has come out of the pandemic is how a campaign slogan which emerged from transnational women’s movements for sexual and reproductive rights, is being invoked by anti-vaxxers, anti-masking and anti-lockdown protesters. Using slogans of “my body, my choice” or “my body, my rights”, these protesters, especially in the US and in Australia, frame COVID-19 restrictions and vaccination programmes as state-led human rights violations against their right to “bodily autonomy”. All while the global COVID-19 pandemic death tolls continue to rise and the well-being of health workers is at the point of depletion.

In the chapter I contributed to the edited volume Gender, Global Health, and Violence: Feminist Perspectives on Peace and Disease and in other published works, I argue that ideological contestations over sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) need to be situated in relation to material relations of power. Examining the global politics of SRHR demonstrates that the re-signification of “my body, my rights” in these contexts is not simply a case of misconstruing what this slogan represents or ignorance of where it comes from. Rather, it reflects deliberate efforts to employ a time-tested and well-developed tactic by Far Right, conservative elites, and religious fundamentalist groups to de-contextualise and appropriate feminist ideas for anti-feminist gains.

My Body, My Rights

The use of “my body, my choice” by anti-vaccine protestors may be convincing perhaps in an environment of disinformation, hate and conspiracy. For instance, the narrative of ‘choice’ matters for people who believe based on unscientific claims that vaccines lead to a range of long-term illnesses or when they mistrust health service delivery. The use of the narrative may reflect an attempt to build common cause with other groups ideologically predisposed to perceive COVID-19 regulations as ‘excesses’ of the State. In the US some of these protesters were also openly pro-Trump and Republicans – who would likely also view gun control as a violation of fundamental human rights. However, it is ultimately flawed because their position on bodily autonomy removes it from political economy: how authority, responsibility and resources are allocated in society and globally.

What we are seeing now with the anti-feminist appropriation of bodily autonomy in the context of COVID-19 is reminiscent of the “rights versus needs” debates on SRHR in the late 1990s and in the aftermath of key UN conferences. Political scientist Rosalind Petchesky traces the dichotomy between “basic needs” and “human rights” to a position first adopted by a pro-life[1] group called the NGO Caucus for Stable Families during the ICPD+5 review process. This view, which was espoused by other Christian Right groups and the Vatican, was based on a critique of development “gone astray” due to the dominance of Western or Global North countries in both the global economy and within feminist activisms. This critique allows these conservative forces to frame specific issues as prerequisites to human survival under the category of “basic needs” while dismissing sexual and reproductive health as “flawed priorities [that] reflect a Western agenda (read, of Western feminists) with a blatant disregard for the genuine needs and priorities of women in the South”.

So, it was no surprise that I encountered the same logic of “rights versus needs” to justify the position of local pro-life groups in the Philippines during the Reproductive Health (RH) debates in 2012. Many of these pro-life groups originate from or are networked with pro-life groups in the US. “Anti-RH” as they were also known locally, questioned the “appropriateness” of a law seeking to publicly fund contraceptives for a country that is still failing to meet the ‘real needs’ of Filipino families, especially women in poverty. Citing resource scarcity, they argued that the government should prioritise ‘real’ solutions to poverty such as building roads and improving basic education rather than giving women access to condoms and pills.

The “rights versus needs” discourse may initially be convincing because it mobilises the language of rational prioritisation to global and national resource allocations and dovetails with feminist critiques of North-South political economic divides. Indeed, it continues to gain purchase including among conservative national governments and elites who are intent on quelling domestic feminist and human rights movements. In effect, this position by the Christian Right was a bid to build common cause on global inequalities by discrediting the transnational women’s movements behind SRHR. It serves to contest and establish who has the authoritative voice on the ‘real world’ problems of poor, ‘Third World’ or ‘Global South’ women.

However, bodily autonomy and SRHR, as articulated by transnational women’s movements then and now have long reasserted that all human rights are equally important and interdependent. They see bodily autonomy as part of broader social justice and peace movements for the creation of safe and healthy environments free from racial discrimination and environmental degradation. Bodily autonomy is understood in relation to reproductive justice which is neither individualistic nor individualising. On the contrary, the impetus for championing SRHR was to resist structural oppressions and to end injustices in all areas of life: “social, economic, gender, racial, environmental, financial, physical, sexual, environmental, disability and carceral.”

Championing sexual and reproductive health and rights was to resist structural oppressions and to end injustices in all areas of life: social, economic, gender, racial, environmental, financial, physical, sexual, environmental, disability and carceral

Continuum of Peace and Replenishing Bodies

When I wrote the chapter in Gender, Global Health, and Violence I drew on research examining gender in conflict and disaster settings to show that so often post-crisis recovery is built on keeping invisible women’s social reproductive labour and the deterioration of their health and well-being. I showed that women’s health is an important indicator for how societies are rebuilding inclusively and on the basis of gender justice in the aftermath of conflicts and disasters. Moreover, I urged that we understand women’s health across the different forms, phases and layers of violence. That is, we need to pay attention not just to physical or bodily harms but also to less visible harms of social discrimination and policies that erode universal health care.

There are clear lessons from my chapter in Gender, Global Health and Violence for envisioning what a post-pandemic recovery would look like. If anti-feminist movements are so keen to leverage the principle of bodily autonomy, then those of us seeking to resist them and enact transformative social change must double down on bodily autonomy too and embrace its radical implications.

From bodily autonomy we see the continuum of peace: for all of us to be able to enjoy our own right to a healthy and fulfilling life, we cannot do it except collectively and by making changes structurally. Bodily autonomy is not simply about whether one can ‘choose’ to wear a mask or not. It entails the indispensability of replenishing bodies through reinvigorated health systems, recognition and valuing of care economies, addressing climate change, and countering hatred and fear with love.

From bodily autonomy we see the continuum of peace: for all of us to be able to enjoy our own right to a healthy and fulfilling life, we cannot do it except collectively and by making changes structurally.

This brings me to why the current instrumentalisation of feminist language to justify the behaviours of anti-vaxxers, anti-masking and anti-lockdown protesters is so dangerous. Protests perverting the language of “my body, my rights” alert us to how patriarchal and racist counter movements (which include women members too) can so readily forge alliances on a global scale to pursue oppressive policies through a shared anti-feminist ideology. The transnational nature of anti-feminism is an alarming trend that requires an equally transnational, cross-sectoral, collective action and responsibility. Because of the threat they pose for global post-pandemic peace and security, we need to better understand the strategies and ways of thinking employed by those who have long waged wars against women’s bodies.

Pro-life is a broader position than simply anti-choice and anti-abortion because these groups link their position on SRHR with opposition to same sex-marriage and LGBT rights on the basis that they believe these to be ‘anti-life’. See AWID, Rights at Risk: The Observatory on the Universality of Rights Trends Report 2017, Available at: https://www.awid.org/publications/rights-risk-observatory-universality-rights-trends-report-2017

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) only, and do not necessarily reflect LSE’s or those of the LSE Centre for Women, Peace and Security.

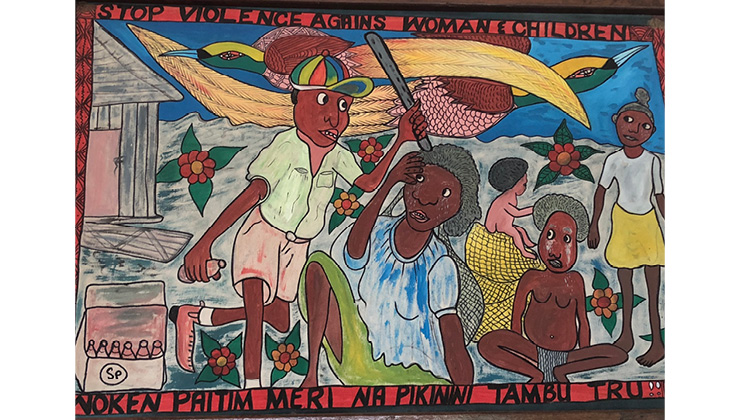

Image: My body my choice sign at a Stop Abortion Bans Rally in St Paul, Minnesota, May 2019. Lorie Shaull CC BY-SA 2.0