As the 26th UN Climate Change Conference comes to a close in Glasgow, Maryruth Belsey Priebe and Tevvi Bullock on why a gendered lens is necessary in climate change indices and reports arguing that it is no longer tenable that gender considerations remain optional in climate-security data collection.

As international scrutiny of the global climate crisis’ security implications intensifies, new indices and reports are regularly being released, detailing how global warming could induce or further exacerbate human, environmental, and state vulnerabilities, fragilities, and insecurities. Although climate risk modeling is a relatively new field, climate-security indices and reports are rapidly gaining in complexity and nuance, reflecting the complicated ways climate change, disasters, (in)security, and conflict intersect, and the ubiquitous relevance of climate security data to global systems of diplomacy, development assistance, humanitarian action, defense, and trade, to name but a few.

However, as climate risks compound, the effectiveness and transformative potential of global responses will be severely hindered if climate-security modeling categorically ignores gender. Gender is an inextricable variable influencing how people differentially cause, seek to prevent, prepare for, and experience the climate crisis. As Ide, et al. have recently detailed, gendered power structures, roles, and identities are critical intervening variables in responding to and preventing climate-related conflicts, and are crucial considerations in promoting climate resilience.

It is imperative that gender is substantively integrated into the data collected and utilised by scholars, practitioners, civil society, policymakers, governments, and multilateral organisations in developing climate security reports, policies, and programmes. Only when gender is employed as a variable can genuinely contextualised, spatially-explicit risk assessments emerge, enabling more comprehensive, actionable insights into the differential, gendered impacts of complex, multi-layered climate crises.

Certainly, there has been growing recognition through global normative frameworks and treaties, including the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Agenda and the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), of the need to foreground and address the gendered dimensions of climate insecurity in building global peace and stability. Global exemplars in data collection and research centred around the gender-climate-security triple nexus have been produced within the past 2 years by a range of leading scholars and institutions, including Gender, Climate and Security (2020), Advancing Gender in the Environment (2020), Climate-Gender-Conflict Nexus (2020); and Defending the Future (2021).

It is imperative that gender is substantively integrated into the data collected and utilised by scholars, practitioners, civil society, policymakers, governments, and multilateral organisations in developing climate security reports, policies, and programmes.

But what of the broader multitude of climate-security indices and reports which play critical roles in informing international, national, and local climate policies and programmes – to what extent are gender considerations present? To briefly survey gender integration levels in prominent climate-security risk modeling and publications, we selected five indices and five reports (found through an internet search) which satisfied the following criteria:

- publicly available and produced by reputable organisations employing rigorous research standards;

- climate-security focused, but not explicitly focused on gender;

- published between 2019 and 2021;

- predominantly international in outlook; and

- at least moderately comprehensive in methodology and/or themes covered.

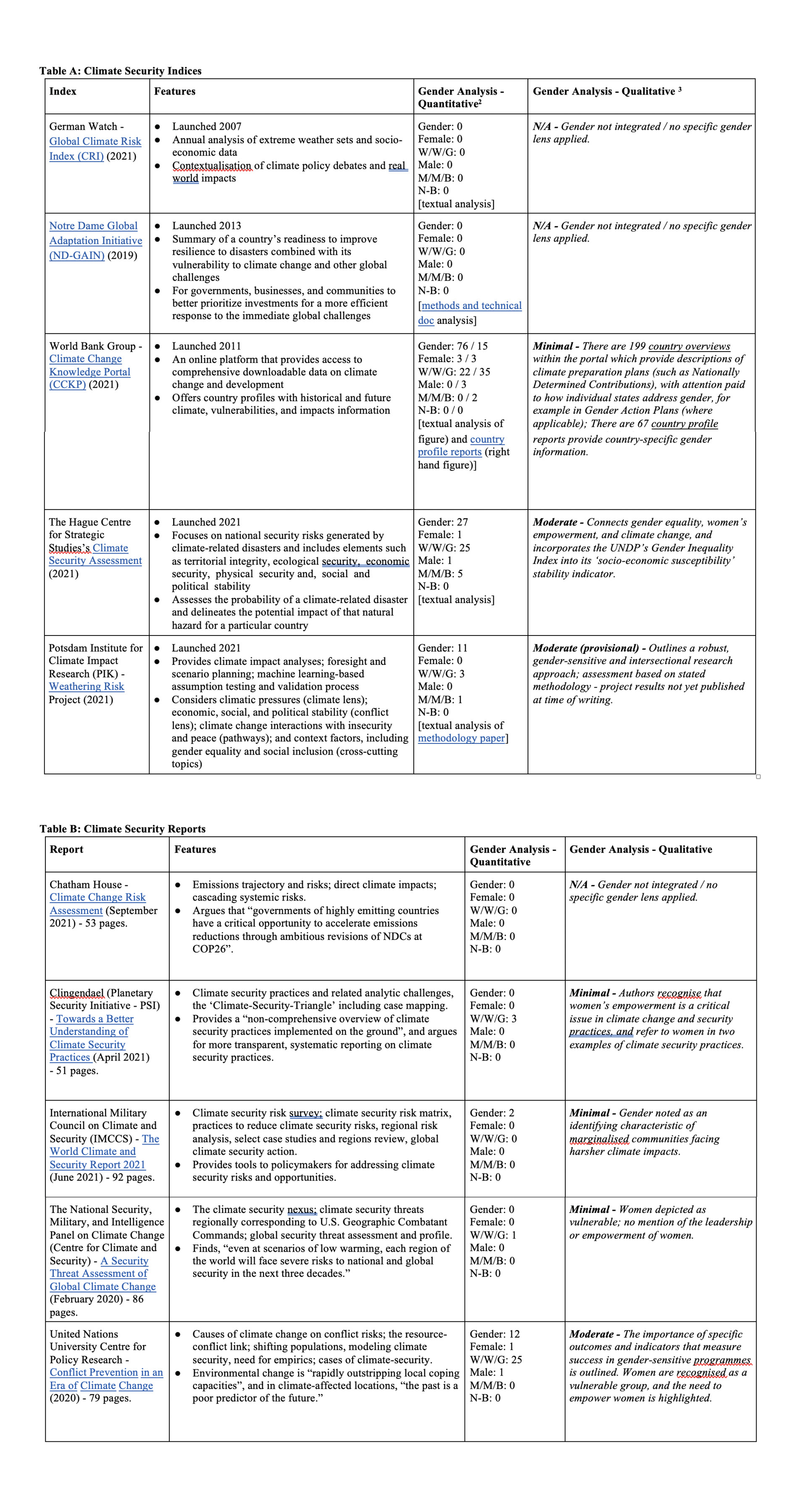

We examined the selected indices by reviewing their methods, indicators, and, where applicable, published analyses for specific gender terms,[1]and conducted a textual analysis of gender terms in the selected reports, excluding non-substantive gender term references (for example in bibliographies). We thereby determined the quantitative extent to which gender was integrated, and concurrently assessed the qualitative strength of this integration. These results are collated in Tables A and B below.

Results Overview

Amidst a still nascent climate-security field of research, from a small sample size our results indicate that noteworthy efforts are being made by some organisations, yet a reticence by others to actively mainstream gender and integrate gender-sensitive analyses in global climate-security datasets and resources still prevails. Moreover, where women’s vulnerabilities are foregrounded but their leadership and empowerment ignored, and where gender continues to be employed as a “placeholder for women,” rendering men and non-binary identifying people largely invisible, a holistic picture and understanding of how to address the relational and interconnected aspects of gendered climate insecurity is negated. Furthermore, without a strong baseline gender perspective, crucial intersectional analyses and fully inclusive policy responses remain even further from reach.

[1] The following gender terms were searched: gender; female; women/woman/girl(s); male; men/man/boy(s); and non-binary. The lack of legally-recognised non-binary and gender diverse categories globally, translating to comprehensive deficits in current ‘gender-disaggregated’ data collection, is itself a significant and underaddressed issue impeding the quest to ensure human rights and achieve gender equality globally.

our results indicate that noteworthy efforts are being made by some organisations, yet a reticence by others to actively mainstream gender and integrate gender-sensitive analyses in global climate-security datasets and resources still prevails

Gender in Climate Security Indices

Across the five selected indices, a mixed level of gender integration was evident. Two indices did not directly address gender: Notre-Dame’s ND-GAIN Index, which provides valuable country-level data and historical trends on national preparedness for global challenges including climate change; and GermanWatch’s Global Climate Risk Index (CRI), which employs MunichRe NatCatSERVICE, one of the most comprehensive global data sets on extreme weather events, with analyses related human impacts (fatalities) and economic losses.

However, three indices in our sample did integrate gender to differing degrees. The World Bank Group’s Climate Change Knowledge Portal (CCKP) offers 67 country-specific risk profiles as well as descriptions of 199 country climate preparation plans (such as Nationally Determined Contributions), with attention paid to how individual states address gender, including in Gender Action Plans (where applicable). Gender is mentioned in 38 per cent of the country overviews and 22 per cent of the country profiles, while, for example, terms related to women are used in only 11 per cent of the overviews, but in 52 per cent of the profiles.

The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies’ Climate Security Assessment explicitly connects gender equality, women’s empowerment, and climate change, and incorporates the UNDP’s Gender Inequality Index into its ‘socio-economic susceptibility’ stability indicator in climate risk assessments. Lastly, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research’s (PIK) Weathering Risk project offers perhaps the most substantive inclusion of gender. Although Weathering Risk’s findings are yet to be published, the project methods section encouragingly outlines that, “a gender-sensitive and intersectional research approach will ensure findings are disaggregated by gender, age and identify groups to better understand the heterogeneity of risks and dimensions of resilience across contexts and actor groups.”

Gender in Climate Security Reports

Our analyses of the selected climate-security reports revealed that, overall, a gender-perspective was not strongly integrated. In four of the reports, all over 50 pages in length – The National Security, Military, and Intelligence Panel on Climate Change’s A Security Threat Assessment of Global Climate Change, Planetary Security Initiative’s Towards a Better Understanding of Climate Security Practices, Chatham House’s Climate Change Risk Assessment 2021, and International Military Council on Climate and Security’s The World Climate and Security Report 2021 – gender terms were used 3 or fewer times in each, with one report making no reference to any gender term. Indeed, ‘Towards a Better Understanding’ outlined that women’s empowerment, whilst important, constitutes a domain which is, “often not the core of climate security practices.”

However, the United Nations University Centre for Policy Research’s Conflict Prevention in an Era of Climate Change scored significantly higher, with 39 references overall made to gender terms. The report recognised gender as an important variable underpinning the differential impacts of climate change on human security, particularly for women, and recommended the development of specific outcomes and measurable indicators for gender in addressing climate insecurity.

Gender in Other Publications, Programmes and/or Events

Importantly, several institutions mentioned here whose indices and reports did not integrate a strong gender lens have sought to address gender and climate change more substantively in other publications, programmes, and/or events. GermanWatch’s policy paper on the water-energy-food nexus specifically examines women’s roles within the sector. Chatham House and Clingendael Institute’s Planetary Security Initiative have hosted online events including Climate Action and Gender Equality and Addressing Gender Dimensions of Climate Change and Security respectively, whilst the Centre for Climate and Security’s Climate Security Risk Briefers report includes a chapter on mainstreaming gender in climate security.

It is positive that organisations are increasingly making commitments to foreground gender in publications, programmes, and events. To ensure the application of a gender lens does not become an isolated or ‘tick-box’ affair, it is critical that organisations ‘de-silo’ their work, and commit to strengthening indices and reports by purposefully integrating gender-sensitive perspectives and gender as a variable into their research methodologies and analyses.

Certainly, disputes as to the necessity of comprehensively integrating gender may arise, as researchers and policymakers can correlate or triangulate a multitude of gender-disaggregated and non-gender-disaggregated data in constructing complex datasets and analyses. In fact, the Georgetown Institute of Women, Peace and Security’s (GIWPS) WPS Index Report (2021) cross-references Notre Dame’s ND-GAIN index, finding the correlation that, “countries where women’s inclusion, justice, and security are protected are also better positioned to mitigate the rising threats of climate change.”

To ensure the application of a gender lens does not become an isolated or ‘tick-box’ affair, it is critical that organisations ‘de-silo’ their work, and commit to strengthening indices and reports by purposefully integrating gender-sensitive perspectives and gender as a variable into their research methodologies and analyses.

But does this negate the importance of globally influential datasets committing to substantively integrating gender? In a highly interdependent, interconnected world categorised by worsening, and in many places existential, climate, ecological, and gender inequality crises, it is no longer tenable that gender considerations remain optional in climate-security data collection, research, and reporting. Ultimately, failing to mainstream gender in climate-security indices and reports contributes to the perpetuation of laws, policies, programmes, and budgets which are gender-blind, structurally inequitable, and environmentally unjust. Policymakers and practitioners need to be provided with every reason and opportunity to draw on gender-disaggregated data in constructing sustainable and transformative climate-security policies and programmes. The responsibility to demand this, and to fight for more gender-responsive, gender-inclusive, intersectional, and equitable responses to the climate crisis, rests with us all.

[1] The following gender terms were searched: gender; female; women/woman/girl(s); male; men/man/boy(s); and non-binary. The lack of legally-recognised non-binary and gender diverse categories globally, translating to comprehensive deficits in current ‘gender-disaggregated’ data collection, is itself a significant and underaddressed issue impeding the quest to ensure human rights and achieve gender equality globally.

[2] W/W/G = women/woman/girl(s); M/M/B = men/man/boy(s); N-B = non-binary.

[3] Integration of gender qualitatively ranked as minimal, moderate or maximal, or N/A.