While the populist right is seen by many to be the home of Euroscepticism, Marley Morris argues that it can be attached to a variety of ideologies, both left and right. As European leaders struggle to find solutions to the economic and debt crisis this gives rise to Eurosceptic populism which is always anti-liberal and distinctly disinterested in nuanced solutions to complex problems.

The economic crisis in Europe will most likely lead to a political crisis. While European leaders meet again and again in an attempt to find a solution to the debt challenge, François Hollande, candidate in the French presidential elections, recently joined the chorus of pro-Europeans warning of a rising Eurosceptic populism.

Many have spoken of the ‘rise of the far right’ since the recession hit Europe. That is misleading – right-wing populist parties were doing well long before the recession – think of Le Pen’s success in 2002 or Haider’s victory in 1999 – and some – like Belgium’s Vlaams Belang – have done rather poorly in recent years. In a recent Channel 4 Documentary Nick Griffin, chairman of the British National Party (BNP), himself admitted that the recession at first hurt the BNP politically. Yet Hollande is surely right that the perception that European leaders have failed to tackle a developing economic crisis is fuelling antipathy to the European Union (EU).

This refocuses liberal anxiety about the far right. It is not the extremists we should be worried about but the much larger group of people who may be sympathetic to Eurosceptic populism without being committed supporters. These are the ‘reluctant radicals’. The risk is that their grievances will be hijacked by populist movements. But where exactly does the populist danger lie?

The populist right is often seen to be the home of Euroscepticism, from the Front National in France to UKIP in the UK. And it is true that right-wing populist leaders are attempting to capitalise on anti-EU sentiment amid the on-going crisis. The Lega Nord is a vocal opposition of Mario Monti’s technocratic government in Italy, disparaging his ties with the European elite; Marine Le Pen is stoking up fear of the EU as part of her campaign for the French presidency; and earlier this month a report commissioned by Geert Wilder’s PVV argued for the financial benefits of the Netherlands leaving the Eurozone.

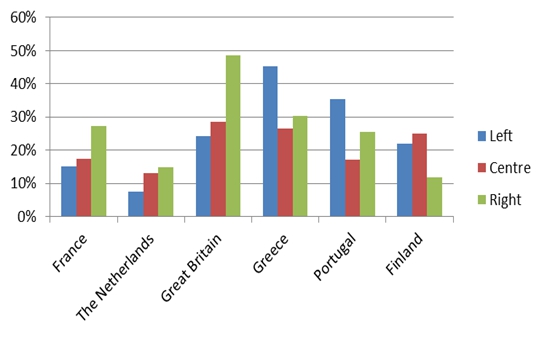

But that is not the whole story. A look at results from last spring’s Eurobarometer survey in Figure 1 suggests that in some countries Euroscepticism is not just the domain of the right. Whilst in Great Britain and France right-wing Euroscepticism dominates – in Great Britain nearly half of right-wingers think that EU membership is a bad thing compared to 24 per cent of left-wingers – in Greece and Portugal, it is the left rather than the right that is more Eurosceptic than expected. 45 per cent of left-wing Greeks think EU membership is bad compared to 30 per cent on the right. In Finland, centrists are more Eurosceptic than the right – 25 per cent think EU membership is bad compared to 12 per cent of right-wingers. Of course, this one question does not tell the whole story about attitudes to the EU, but it is suggestive of where on the political spectrum hostility lies.

Figure 1 – Proportion of citizens that think their country’s EU membership is a bad thing

Source: European Commission/Eurobarometer 75 (3), May 2011

These figures are reflected in the kinds of populist Eurosceptic parties that dominate in each country. In Britain, France and the Netherlands it is right-wing populism that takes the Eurosceptic reins. In Finland the Eurosceptic populist Finns Party – formerly known as the True Finns – has experienced a dramatic surge in support. This party combines left-wing economic policies with traditional right-wing social values and is more moderate when compared to parties like the Front National. Meanwhile, it is the far left in Greece that is benefitting the most from the on-going debt crisis. After the Greek coalition government voted to approve the second austerity package, support for the mainstream parties dropped dramatically, whilst the three far left parties polled at a combined total of around 37 per cent. And at the same time the country is rocked by violent protests and social unrest.

Even in the Netherlands – where right-wing populism is strong and where the data doesn’t point to a large Eurosceptic left – the left-wing populist Socialist Party has shot ahead in the polls, taking a chunk out of Wilders’ vote in the process. Dutch politics may well descend into an uninspiring “battle of the populists”.

It would be a mistake to think that just because populism is not a component of the far right it is not dangerous. Populism in all its guises is anti-liberal, uninterested in nuanced solutions to complex problems, and always has the potential to be xenophobic. The Finns Party share similar anti-immigrant attitudes to parties like the Danish People’s Party. Meanwhile, Emile Roemer, leader of the Dutch Socialists, said he “understood the sentiment” behind a website the PVV established that demonises Eastern Europeans.

As Paul Taggart has said, populism is chameleon-like – it can be attached to a variety of political ideologies, both left and right. Moreover, the EU is everything that populism hates – a project that appears elitist, bureaucratic and distant. It is an undertaking that is easy to characterise as perpetrated by political elites at the expense of the people. This explains why populist parties and movements of both the left and the right are able to capitalise on opposition to the European project.

There is no doubt that populist Eurosceptic movements have real influence in the current crisis. The report now being touted by Wilders’ PVV – which provides support to the current Dutch minority coalition – could force the Dutch government to drive a harder bargain with troubled Southern European countries. Those who think Europe is worth fighting for need to be cautious. Before moving forward to protect Europe from decline, they must make sure to look both ways.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics

_____________________________________

About the Author

Marley Morris – Counterpoint

Marley Morris – Counterpoint

Marley Morris is a researcher at Counterpoint on the Recapturing Europe’s Reluctant Radicals project. He has a combined Masters in Maths and Philosophy from the University of Oxford. Prior to his work at Counterpoint Marley was at the Violence and Extremism programme at Demos where he co-authored the report ‘The New Face of Digital Populism’. He has written on populism, social unrest and immigration for a number of blogs, including OpenDemocracy and Liberal Conspiracy.

You say that “[p]opulism in all its guises is […] uninterested in nuanced solutions to complex problems” but also that one of these populist parties commissioned a report on the Euro, which was covered in the Telegraph (and indeed City AM, which is where I read about it).

Is it really credible to say that people who are uninterested in nuanced solutions would bother paying money to fancy City firms for cost benefit analyses of monetary policy? Or is it that populists have to take policy development seriously just like anyone else if they want to get anything done, and any evidence to this effect must be omitted or, as here, ignored?

Thanks for your comment Martin. You raise an interesting point – does Wilders’ Lombard Street report on leaving the Euro show that he is interested in nuanced answers after all, contrary to what I say about populism? Well, I would be sceptical. The conclusion of the report – or at least what Wilders took from it – is still a simple solution – leaving the Eurozone – to a complex problem, even if the argument for it is a subtle one. I am not convinced that Wilders was interested in the content of the report at all other than its final conclusion, which backed up what he had been hinting at anyway. So no contradiction after all, perhaps?

Dear Mr. Morris,

I came across your interesting post while researching for my thesis. Amongst others I am researching Euroscepticism and populism and I was wondering whether you could perhaps be more specific on the source of the graph you have used (Figure 1). I have gone through the Eurobarometer 75 Spring 2011 (Public opinion in the EU) but I cannot find this specific graph. Am I looking in the wrong Eurobarometer-report?

Thank you very much in advance for your time and help!

Apologies, only just came across this message! Happy to help if it’s still relevant, my email is marley.morris@counterpoint.uk.com. The reason you couldn’t spot the graph in that report is because I created the graph from the data directly, which you can get from here: http://www.gesis.org/en/eurobarometer/data-access/