Trump may represent a challenge to Brazil and multilateralism, but his government also offers unique opportunities for Brazilian foreign policymakers to advance economic integration and expand the nation’s leadership in the international community, writes Mark S. Langevin.

Trump may represent a challenge to Brazil and multilateralism, but his government also offers unique opportunities for Brazilian foreign policymakers to advance economic integration and expand the nation’s leadership in the international community, writes Mark S. Langevin.

The United States under President Donald Trump will challenge and even offend Brazil’s foreign policy principles, but this should not deter Brazilian diplomacy from engaging Washington to advance well-defined interests. Trump’s “America First” vision of US foreign policy is mostly bluster, but it does underline a persistent vision of foreign policy marbled together from currents of nativist isolationism and liberal imperialism. His imperfectly articulated version of America First could prove to be a passing fancy among US voters seeking protection from the socio-economic dislocation of economic globalisation. But Brazil needs nonetheless to move on overlapping points of mutual interest to strengthen its own economy and renew its pivotal role in global governance.

Back to the future: Trump’s “Jacksonian” foreign policy

According to Walter Russell Mead, the rise of Trump should be understood as the reemergence of a strand of “Jacksonianism” that represents the outlook of those…

…skeptical about the United States’ policy of global engagement and liberal order building – but more from a lack of trust in the people shaping foreign policy than from a desire for a specific alternative vision. They oppose recent trade agreements not because they understand the details and consequences of those extremely complex agreements’ terms but because they have come to believe that the negotiators of those agreements did not necessarily have the United States’ interests at heart.

Prior to his election, Trump seized on these sentiments to walk away from the US-led international liberal order and pending preferential trade agreements:

We will no longer surrender this country or its people to the false song of globalism. The nation-state remains the true foundation for happiness and harmony. I am skeptical of international unions that tie us up and bring America down, and will never enter America into any agreement that reduces our ability to control our own affairs.

Many of Trump’s working class voters reject the liberal global order tendered by the Democratic Party of Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, as well as the leadership of the Republican Party. Trump and his supporters may fail to understand the checks and balances of constitutional republican government, but Washington’s liberal and bipartisan establishment underestimates just how devastating economic globalisation can be to those without a university education or a sturdy safety net.

Overlapping reactions to globalisation in the US, Brazil, and beyond

Trump’s “America’s First” decries the excesses of capital and trade liberalisation, but without offering logical policy alternatives that respond to the growing negative externalities fuelling Jacksonian impulses in the US For decades Brazil danced to a similar tune, with national-developmentalism premised on industrial protectionism, inefficient local-content policies, and the politics of kickback corruption. Trump did not borrow from the Brazilians, but the coincidence says a lot about how growing numbers of workers from Michigan to Minas Gerais experience economic globalisation and reject many features of the global liberal order. Brazil’s recent economic bust also demonstrates how exchange-rate populism and the commodity boom ultimately challenged the limits of national development in an increasingly globalised world. More to the point, the global economy rewards productivity and punishes those whose work does not measure up to the rising tide of global competition. There is no escape from this fundamental fact of the twenty first century.

Economic and foreign policymakers must contend with this rising tide or drown. Mead addresses this issue in terms of Brasilia, Washington, and beyond:

The challenge for international politics in the days ahead is therefore less to complete the task of liberal world order building along conventional lines than to find a way to stop the liberal order’s erosion and reground the global system on a more sustainable basis. International order needs to rest not just on elite consensus and balances of power and policy but also on the free choices of national communities – communities that need to feel protected from the outside world as much as they want to benefit from engaging with it.

This fundamental political challenge also reflects several of Brazil’s long-held foreign policy principles, forged from decades of struggle to influence the global order while maintaining the national autonomy required to guide economic and social development. Brazil has advocated equality among nation-states, multilateral economic cooperation that allows the developing world to prosper and even “catch up,” and sufficient policy space for national governments to eliminate deep-seated poverty and social exclusion. Not coincidently, Trump’s globalisation angst, his unapologetic nationalism, and his focus on manufacturing industries overlap with Brazilian political frames and policymaking, whether foreign or domestic. Given the overlap, should Brazil take every opportunity to press the Trump White House for reforms to the global liberal order that would favour not only Brazilians but also Trump’s working class supporters? No one should discount the possibilities.

Brazil’s opportunity to formulate a strategic response

Oliver Stuenkel, of the Fundação Getúlio Vargas, argues that Trump’s impact on Brazil will be negative for four reasons:

- the increase in US protectionism

- the increase in the US Federal Bank’s prime interest rate

- the rising geopolitical tensions

- the increasing fragility of democratic governance around the world

But Stuenkel rightly suggests that these factors also create new opportunities for Brazil, including a potential expansion of export markets in Mexico and Asia.

Economic aspects of a strategic Brazilian response

Both US presidential candidates promised to walk back former President Obama’s regional trade policies, including the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). As Mead notes, both US and Brazilian policymakers are reassessing their respective nations’ insertion into the global economy. Trump promised more manufacturing jobs and the Temer government in Brasilia is signalling an interest in deepening trade liberalisation. While it appears that each country is moving in different directions, this trend does not mean that Brazil and the US would be unable to find a middle ground that boosts exports from both countries and contributes to the modernisation of Brazilian industry.

Brazil must decide what it wants from the US economy, especially with respect to the manufacturing sector. If Brazilian policymakers and industrial leaders decide that it is time to integrate the national industrial capacity into global value chains by concentrating on higher value-added manufacturing fragments, then engaging Washington to lower the barriers to cross border economic cooperation and industrial integration makes sense.

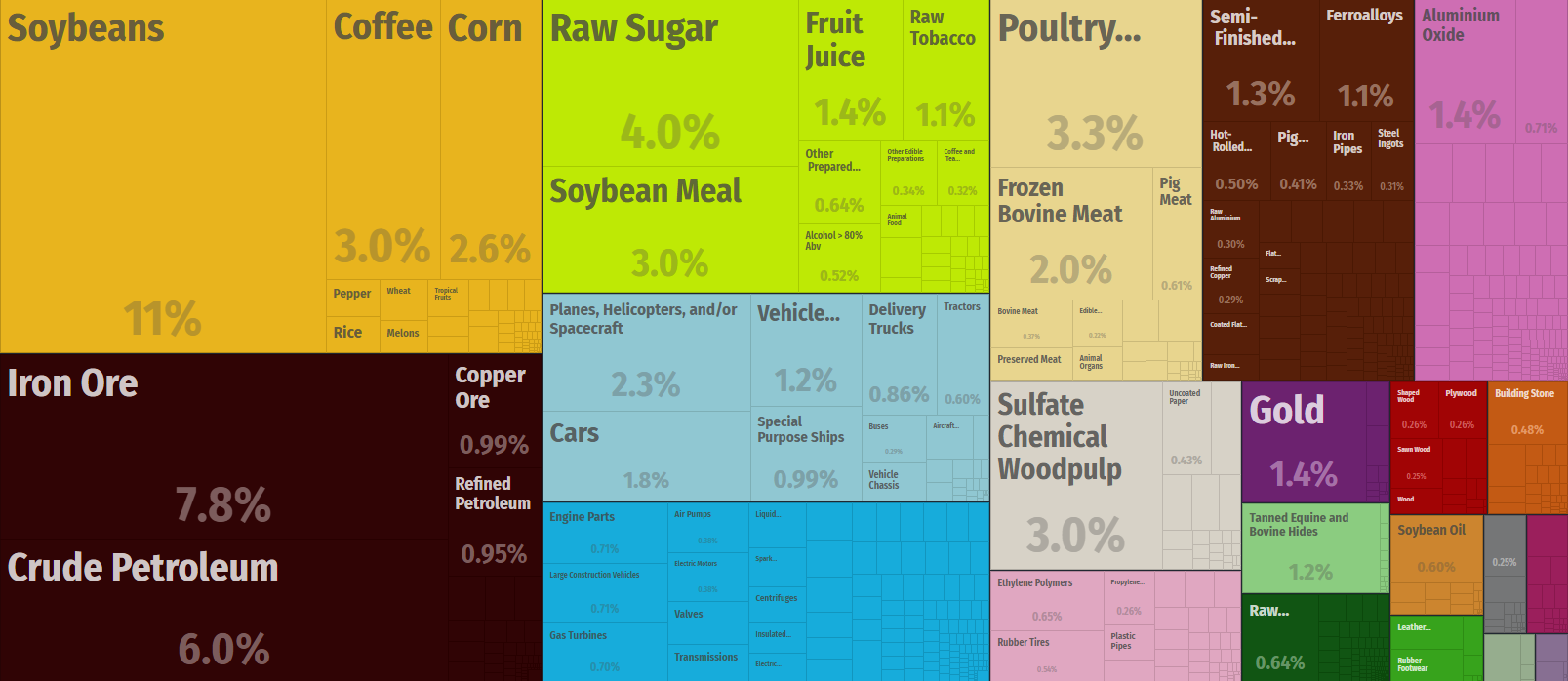

To this end, the Executive Manager of Foreign Commerce at the National Industrial Confederation (CNA), Diego Bonomo, argues that Brazil should adopt a building-block strategy focused on particular issues and sectors that can benefit both nations. Trump may not be keen on ratifying large regional agreements today, but such a political position does not preclude deepening economic cooperation if Brazil knows what it wants. The US positive trade balance with Brazil and the higher value added composition of the binational trade portfolio provides Brazilian foreign policymakers with a strong argument that deepening trade and investment can benefit both countries. Trump wants to increase exports and Brazil needs to take advantage of the US economy to stimulate investment, encourage technology transfer and innovation, and broaden the base of international markets for competitive manufacturing exports (both intermediate components and finished goods). Stuenkel’s pessimism may turn out to be correct, but only if Brazil backs away from Washington rather than amplifying its engagements on the economic front.

Stuenkel also proposes that hikes in the US prime interest rate will undercut foreign investment in Brazil. Such an outcome is expected in part, but Brazil should focus on long-term foreign direct investment that leads to major improvements in infrastructure, deepens capital markets, improves corporate governance, raises labour productivity, and prepares Brazil to become increasingly competitive in a globalising economy. Brazil can successfully counter expected rises in US interest rates by reforming those policies that currently discourage foreign direct investment in long-term productive projects and by focusing on a national workforce-development strategy capable of meeting the demands created by foreign direct investment and economic integration. Such policy reforms are not only necessary for economic development, they could also strengthen Brazil’s hand in multilateral negotiations over the future direction of the global economy.

Diplomatic aspects of a strategic Brazilian response

Brazil’s longstanding commitment to multilateralism needs to be refreshed and resourced, but it promises to play a notable role in addressing the rising challenges to collective security around the world and could serve to help steer the US and other nuclear powers toward more constructive dialogue both within the United Nations and other international arenas. The Trump government, like any other Republican executive in the United States, is predisposed toward unilateralism. Yet, Trump speaks of a less interventionist government that promises to minimise national risks and resource allocation.

This scenario creates a compelling opportunity for Brazil to retake its pivotal, multilateral role. Foreign Minister Aloysio Nunes (right) recently wrote of the “Humanitarian Promise” to abolish nuclear weapons, but the real and present threat is North Korea and the possibility of an arms race in Asia. Rather than just attending United Nations conferences and avoiding the White House, Brazilian foreign policymakers should walk through the front door and seek ways to resolve collective security challenges through bilateral and multilateral cooperation and burden sharing.

Trump is fickle and his foreign-policy credentials are in question, but this should not impede Brazil from engaging the US government, promoting greater multilateral dialogue, and serving as an honest broker between Trump, the BRICS nations, and whoever else is willing to confront mounting challenges to collective security. Brazil holds more cards that it has played in recent years, but the nation’s political leadership must decide to make the deals necessary to move such an agenda forward, and this requires greater security cooperation with the US

The recent announcement that Brazil and the US will jointly develop and sell defence-related products signals a step forward in bilateral relations. The Brazilian Defence ministry heralded the agreement as the key to “important partnerships in technology that will provide an important incentive for our defense industry as a whole.” These are the types of building-block agreements advocated by Bonomo: providing opportunities for Brazilian industry to modernise, increase competitiveness, and deepen the manufacturing sector’s integration into global value chains thanks to innovation and technology rather than the size of the national marketplace. Moreover, the agreement begins to address the bilateral strategic gap that prevents pivotal cooperation on regional and global matters of collective security. Brazil needs to guard against losing autonomy in both its bilateral and multilateral initiatives, but such caution should not prevent foreign policymakers from carefully defining national interests and articulating them directly to the Trump administration to find points of common concern and possible cooperation.

National and regional solutions to changes in US trade policy and democracy promotion

Stuenkel also worries about the future of democratic governance for good reason. It is improbable that Trump cares much about the state of democracy in Brazil or around the world. Trump will not allocate much presidential diplomacy or budgetary resources to democratic development either. Yet, exporting democracy has always been a dubious enterprise: just ask the Afghans and the US Marines. The rise of Trump did not undermine democratic governance around the world, nor will his apparent indifference determine the future of representative political institutions. Stuenkel is right to warn of the increasing fragility of democracy, but wrong to suggest that Trump can singlehandedly degrade democracy around the world. If anything, the Trump presidency demonstrates that the fundamental checks and balances of constitutional government can effectively curb populist authoritarianism. Brazil must resolve its own political crisis through constitutional mechanisms and restore public confidence through aggressive prosecution and prevention of corruption to effectively promote democracy by example around the world. Brazil’s struggle for democratic accountability will be historic if it prevails, and such an outcome is likely to have a much more profound impact on governance around the world than the rhetorical flourishes and tweets discharged by US President Trump. Brazilians should not underestimate their own potential for promoting democracy by example.

Stuenkel is also right to point to the double-edged sword of Trump trade policy. Brazil should deepen economic and political cooperation with Mexico and many of the Asian nations, including technology-intensive countries like Japan and emerging giants like Indonesia. Regardless of Trump, Brazilian foreign policymakers need to accelerate talks, negotiations, and partnerships based on bilateral interests. Trump’s approach to Mexico does create a new moment for Brazil-Mexico bilateral relations, but NAFTA and US-Mexico relations are woven through with vested interests that are stronger than Trump’s tenuous grasp on trade and immigration policies. Republican dominated states such as Arizona and Texas are unlikely to embrace Trump’s populist retreat from Mexico. It is more likely that Trump will fall back from his “wall” position to allow the status quo to prevail. But even if he doesn’t, Brazil should explore every opportunity to expand cooperation with Mexico, as Stuenkel suggests. Brazilian foreign policy should be tooled to integrate manufacturing, expand trade in goods and services, and search for ways to work with Mexico on global governance issues. Trump cannot determine the outcome of such bilateral efforts, and he will need to adapt his own foreign policies in tandem with measurable improvements in Brazil-Mexico relations. Moving on the Mexican relationship will most likely improve Brazil’s standing in Washington and increase the possibilities for greater bilateral cooperation with the Trump government.

Brazilian foreign policy in the Trump era: a chance as much as a challenge

Trump may represent a challenge to Brazil and multilateralism, but his government also offers unique opportunities for Brazilian foreign policymakers to advance economic integration and expand the nation’s leadership in the international community. Brazil should not be deterred by the Jacksonian moment in the US. Rather, the nation’s political leaders and foreign policymakers should redouble efforts to craft a bilateral agenda that speaks to the pressing economic issues facing Brazilians and US citizens, while also addressing the rising tide of security challenges posed by nuclear proliferation, internationalised civil wars, and the innumerable refugees fleeing Syria.

A majority of US citizens, including many who voted for Trump, share Brazil’s outlook on the economy and global governance. The question is not so much whether Trump will be bad for Brazil, but whether Brazil can intensify collaboration with US citizens and their representative organisations to shape a bilateral agenda that not only engages the Trump government, but also appeals to Brazilians by retaining sufficient autonomy to respond to national challenges and opportunities.

Trump’s Jacksonian lens is only one side of the story. It is up to Brazil to write the other half.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Mark S. Langevin – George Washington University

Mark S. Langevin – George Washington University

Mark S. Langevin, Ph.D, is Director of the Brazil Initiative and Research Professor at the Elliott School of International Affairs-The George Washington University, Director of BrazilWorks, and Member of the International Council of the Centro Brasileiro de Relações Internacionais (CEBRI). He can be contacted at: langevin@gwu.edu