Deportations respond to the domestic logic of controlling immigration, or at least an illusion to do so. But there is an unintended outcome of deportations that so far has been neglected. Christian Ambrosius (Freie Universität Berlin) and Covadonga Meseguer (ICADE) found that the deportations not only carry social and economic burdens but a change in the views that citizens in Latin America have of the United States.

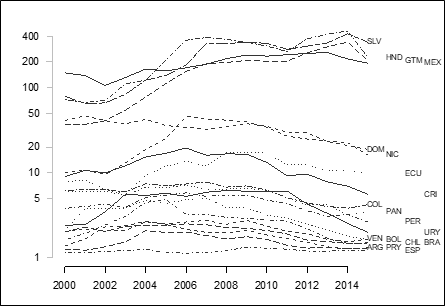

The forced return of migrants who don’t qualify for residence or refugee status is part of the migration policy toolkits of most destination countries. The United States of America has carried out the highest number of deportations over the last decade worldwide: Between 2000 and 2020, the US returned a total of 6.4 million migrants, 90% of whom were sent back to Latin America and the Caribbean, according to the US Department of Homeland Security. In some countries, such as El Salvador or Honduras, the cumulated number of deportees is equivalent to 5% of their current population stocks. Other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, such as Guatemala, Mexico, the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua, have received a considerable number of deportees per capita, as Figure 1 illustrates.

Deportations respond to the domestic logic of controlling immigration, or at least an illusion to do so. But they also generate unintended effects in migrants’ countries of origin: For instance, violent gangs in Central America have been the result of massive deportations after the children of Central American migrants who grew up in urban peripheries of the US were returned as young adults, many of them after having been involved in illicit activities. Also, violent crimes increased in other countries of Latin America. This could result from several direct and indirect effects back home, including the specific targeting of deportees by criminal groups or as a result of the socioeconomic implications such as the loss of income from remittances or unsettled debt from financing migration.

In our latest research, we focus on an unintended outcome of deportations that has so far been neglected. Emigration usually generates positive perceptions among those staying behind and increases trust in the countries where their relatives live. In addition to sending financial remittances to their families back home, these individuals also transmit values and beliefs from their destination countries to their friends and relatives through the so-called social remittances. These help improving the knowledge about the host country and reduce stereotypes or prejudices. The image created around destination countries rests, to a large degree, on the transnational links that migrants create. In contrast, the social and economic burdens that come with deportations radically change the view that citizens in Latin America have of the United States.

El Salvador: Deportations undermine positive attitudes towards the United States

El Salvador presents a particularly compelling case. With large waves of out-migration starting during the civil war in the 1980s, more than a fifth of the country’s population lives in the United States today. Migrants’ exposure to a different culture and the new opportunities created abroad were also reflected in the opinions of Salvadorans regarding their powerful neighbours in the North. In 2000, 92% of all Salvadorans had a good or very good opinion of the US, more than in any other country in Latin America. However, 18 years and more than 250,000 deportations later, this percentage had dropped to 62%, indicating a notable shift in sentiment towards the United States. We postulate that the disenchantment is also the result of deportation practices. We test the relationship between deportations and Anti-American sentiments formally by exploiting subnational variation in the arrival of deportees. In some municipalities – mainly in the North-Western area of Chalatenango and the Eastern parts of San Miguel and Morazán – the number of deportees registered over six years is equivalent to 5% to 10% of their population size. It is in these municipalities where trust in the U.S. declined most.

A common pattern

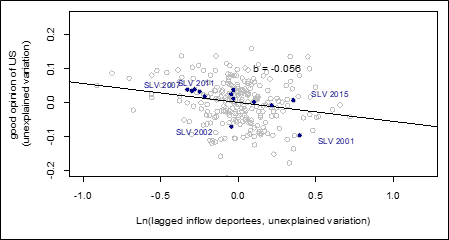

El Salvador is not a singular case. We tested the relationship between deportations and citizens’ opinions concerning the United States in 19 countries from Latin America and the Caribbean from 2000 to 2015. Our data reveals a coherent pattern: The increase in forced returns is associated with a worsening of Latin American citizens’ opinions regarding the United States.

In Figure 2, we depict the correlation of logged deportees in the previous year with the share of persons who had a good opinion of the United States. We control for country-fixed effects that don’t vary over time (such as geography or institutional legacies) as well as country-specific time trends. On average, a ten percent increase in the arrival of deportees is associated with roughly half a percentage point drop in the share of people who have a good or very good opinion of the US.

The geopolitical implications of deportations

These unintended outcomes of migration policies matter because mass public opposition towards the United States can be used by populist leaders to implement radical foreign policy changes. For instance, the current president of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, has cut diplomatic relations with Taiwan in a rapprochement to China; he has courted Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey as part of his strategy to diversify trade and investments; and he has introduced the use of cryptocurrency to challenge the Salvadoran economic dependence on the US dollar. More recently, El Salvador has joined the ranks of other nations with an Anti-American stance – Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Bolivia – in their silence on the United Nations resolution calling for an end to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

All these actions indicate a clear departure from the country’s traditional geopolitical alignment with the United States. Notably, a drop in positive opinions towards the US seems to have preceded President Bukele’s turn in foreign policy. His actions suggest that he has not been ignorant of the widespread resentment against the US that has been mounting among Salvadorans over the past two decades. Deportations not only put a significant burden on migrants and their countries and communities of origin, but they also have unintended costs for destination countries in terms of foreign policies.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

• Banner image: A migrant shows his injured hand to a US border patrol agent / Ringo Chiu (Shutterstock)