A Global Conceptual History of Asia, 1860-1940 aims to explore the changing concepts of the social and the economic during a period of fundamental change across Asia. Case studies show how adopting Western words reflected regional concepts of economy and society. Hagen Schulz-Forberg and his contributors are on the cutting-edge of transnational history, writes Jeff Roquen.

A Global Conceptual History of Asia, 1860-1940. Hagen Schulz-Forberg. Pickering & Chatto. 2014.

A Global Conceptual History of Asia, 1860-1940. Hagen Schulz-Forberg. Pickering & Chatto. 2014.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the first wave of globalization in the post-Napoleonic era, which had been fueled by a burgeoning humanitarian movement and the advent of instant communication, was approaching its zenith. Slavery had not only been abolished in the Spanish colonies (beginning in 1820), the British Empire (1833), the United States (1865), and Brazil (1888), but serfdom had also come to an end in Western Europe and Russia (1861). Concurrent to the completion of the Suez Canal and the Transcontinental Railroad in the United States (1869), telegraph cables newly connected London to disparate parts of the world across the Atlantic, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean.

As a result of rapid technological innovation and a decline in religious dogma, the relationship between man, the state, and the world underwent a transformative and worldwide reconceptualization. In an edited collection of scholarly essays on how Western ideas of society and economy penetrated, permeated, and ultimately remade Asia and the expanse of the late Ottoman Empire, the potency of nineteenth century European thought and its impact on the Far East has been brilliantly illuminated and robustly measured in a volume by Hagen Schulz-Forberg entitled A Global Conceptual History of Asia, 1860-1940.

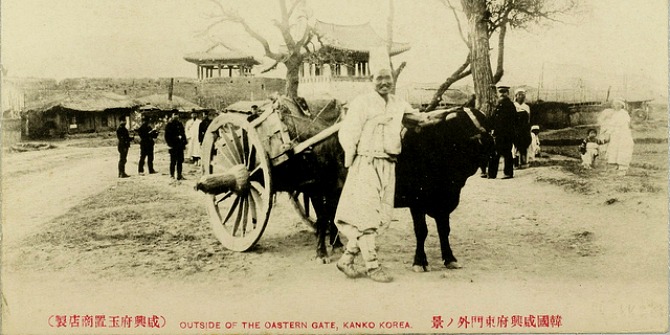

In the immediate decades subsequent to the end of its isolation in 1876, the Korean Kingdom, according to author Myoung-Kyu Park, was fundamentally altered by the introduction of Western political concepts. In 1881, the Joseon dynasty, which had ruled the peninsula since 1392, sent a number of students to post-Mejji Restoration Japan and China under the fading Qing dynasty to gauge the benefits of modernization. From the intercultural exchange, two word-concepts, gyoengje (economy) and sahoe (society) were derived from the Japanese terms keiji (economy) and shakai (society) and employed to rebalance the power of the state. Over the next decade, Koreans challenged their elitist Confucian order and demanded an expansion of individual and property rights based on the two terms. After the fall of Joseon in 1897 and the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910, Park effectively demonstrates how gyeongie and sahoe served as the conceptual basis of the national March First Movement for independence in 1919 – a year pregnant with the idea of “self-determination” as espoused by American President Woodrow Wilson. In China, the same two concepts also worked to undermine its archaic regime.

Two essays on China in the late and post-Qing era entitled “Differing Translations, Contested Meanings: A Motor for the 1911 Revolution in China?,” and “Notions of Society in Early Twentieth Century China, 1900-25” by Hailong Tian and Dominic Sachsenmaier respectively, reveal the extent to which the imported word shehui (society) served to remake the state. On the basis of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address (19 November 1863), Sun Yat-Sen (1866-1925) preached “Three Principles” in his revolutionary campaign: Minzu (“The people’s relation or government of the people”), Minquan (“The people’s power or government by the people”), and Minsheng (“The people’s welfare or government for the people”). For his rival Liang Qichao (1873-1929), social implied restructuring China’s enervated national institutions amid threats to its sovereignty. Despite challenges to the power of the ruling clique, both the Empress Dowager and the entrenched term for “social” (qun) remained ascendant for several more years after the failed scholar-bureaucratic Wuxu or Hundred Days’ Reforms of 1898.

By 1905, however, shehui, which had been linguistically culled from xiakayi in Japanese, began to supplant qun and ran intellectually parallel to Sun’s principle of Minsheng. After a long quest to end extreme forms of patriarchy (i.e. footbinding and concubinage) and peasant poverty through the implementation of a socialist program, Sun triumphed briefly in the wake of the Revolution of 1911. Yet, the ensuing power vacuum resulted in another conceptual contest between proponents of shehui and advocates of qun – led by the scholar Yan Fu (1854-1921). By the late 1910s, Chinese students, who had studied Western concepts of society abroad, had infused nationalistic meaning into shehui and demanded both a combination of socialist and democratic reforms and a strong, unified state. Although Tian and Sachsenmaier unquestionably enlighten the tumultuous events of late and post-Qing China, the anti-modernist Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901 deserves larger consideration in evaluating the intellectual dynamics of the era.

In “The Conceptualization of the Social in Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Arabic Thought and Language,” Ilham Khuri-Makdisi analyzes the Tanzimat or the reformation of the languid Ottoman Empire. From 1830-1880, Constantinople officially ended social and legal discrimination against non-Muslims and introduced measures to distribute land on a more egalitarian basis. When intellectuals in Beirut and Cairo injected Western ideas of individual rights and citizenship into Arabic culture, three concepts, sawalih mushtaraka (“shared benefits or public interests”), qawm (“a people”), and tamaddun (civilization), inspired an anti-elitist drive for a new hay’a ijtima’iyya (social configuration). In order to achieve a genuine state of tamaddun, Beirut scholar-reformer Butrus al-Bustani (1819-1883) declared that ‘adl (justice) and huququhum al-jumhuriyya (republican rights) were essential to ensuring the political and material well-being of the community. These semi-secularized terms merged with other hermeneutically-modified concepts, including umma (“nation”), irtiqa’ (“progress and evolution”), and ma’arif (“knowledge”), to both recognize and give primacy to “civil society.”

By the 1880s, the concept of social had arrived and was being disseminated throughout the Ottoman Empire. Influential newspaperAl-Muqtataf, which became a journalistic organ of Western ideas, published “Al-ijtima ‘al-bashari aw al-‘umran’” (“Human Society or Civilization”) by Bustani’s Egypt-based contemporary Shibli Shumayyil (1850-1917) in 1885. Rather than a “crowd,” Shumayyil re-articulated the term al-jumhur as the “public” or the “masses.” At the same time, a number of reformist intellectuals also began to embrace both the concept of al-iqtisad al-siyasi (“political economy”) and the cooperative socialism of French intellectual Charles Gide (1847-1932). Although successful to a degree, their valiant attempt to make the state subservient to the idea of “society” failed to save “The Eternal State” from collapse in 1923.

The remaining essays, which assess the conceptual impact of the social and economic in early twentieth century Malaya (Paula Pannu), the Dutch East Indies (Leena Avonius), and Siam (Morakot Jewachinda Meyer) – along with an article on the two semantic concepts through time, space, and culture by Klaus Karttunen, prove equally engaging and accomplished. In all, A Global Conceptual History of Asia, 1860-1940 sheds new light on fin de siècle Asia by uncovering the complex and revolutionary socio-intellectual currents of the age. As such, Schulz-Forberg and his contributors are on the cutting-edge of transnational history.

Jeff Roquen is an independent writer and a PhD candidate in the Department of History at Lehigh University in Pennsylvania (USA).