Revolution is My Name: An Egyptian Woman’s Diary from Eighteen Days in Tahrir. Mona Prince. IB Tauris. November 2014.

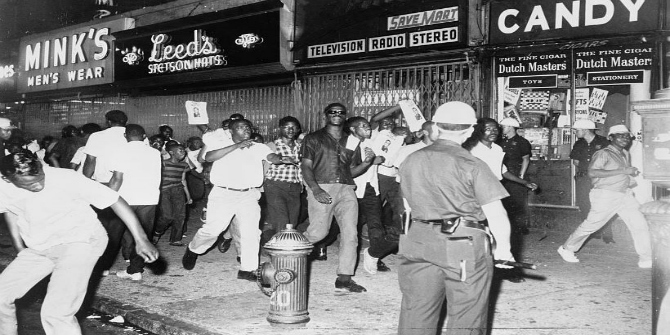

In July 2013, the Egyptian military ousted the democratically elected but deeply illiberal president Mohamed Morsi. The generals who led the coup presented their actions as an attempt at “national reconciliation”. In reality, it was the restoration of a military dictatorship under General Abdul Fattah al-Sisi. The violent repression that followed has made it easy to forget the sense of optimism that the 25 January 2011 revolution against Hosni Mubarak engendered in Egypt and beyond. Mona Prince’s memoir Revolution is My Name: An Egyptian Woman’s Diary from Eighteen Days in Tahrir (2014) is a vivid reminder of those days.

Prince, an associate professor at Suez Canal University, has written a personal account of the revolution as was experienced by a participant on the front line. Her reflections provide necessary texture to the many dry scholarly works calculating the social forces and high politics at play in Egypt, and they show how the changing political scenary was viewed from the ground up. The title captures how the personal and the political are closely intertwined, and Prince vividly maps the journey from academic to revolutionary with all the detours and problems you would expect in such a fraught environment. This memoir is rich with hard-earned insight, but two themes in particular stand-out: the role of social media in the revolution and the relationship between Egyptians and the military.

On the eve of the uprising, an email, quoted in full by Prince, was circulated. It urged the more privileged members of Egyptian society to stay home. It also confidently asserted that, “[u]sually, when popular uprisings erupt, the class that rebels is not…the one that has access to a DSL connection. I have never heard of revolutionaries who have accounts on Twitter or who have revolutionary meetings through a group on Facebook.” This proved to be very short-sighted. It is true that the Arab Spring was no more caused by social media than the 1979 Iranian revolution was caused by cassette tapes. It is also true that much of the commentary about the role of Facebook and Twitter did form a rather patronising narrative that presented, once again, the West as the prime-mover behind events, with Arabs as simple objects being acted upon by outside forces. At times it felt that Mark Zuckerberg was being recast in the role of a modern day Lawrence of Arabia.

Still, as the repeated references to Facebook in Revolution is My Name demonstrate, social media did play an important part in Mubarak’s downfall. Two important functions are discernable here. Firstly, social media was an alternative source of information which could undercut the pro-government news channels. Prince is scathing about the mainstream media. “I have no idea,” she writes, exasperated, “how these unprofessional, ignorant, half-literate people ever came to own and run all these television channels.” Secondly, sites such as Facebook were a useful tool for organising. The above quoted email, getting it wrong again, confidently asserted, “[w]hat I know for sure is that normally [revolutionaries] distribute flyers to incite revolt, but I have never heard of revolutions that are planned on BBM.” The author of the email must have been surprised the next day when demonstrations organized largely through Facebook pages such as “We Are All Khaled Said”, ballooned into the protests that brought down Hosni Mubarak. The powerful role played by social media is, in fact, well captured in a joke that Prince retells: “When Mubarak went to heaven he met Sadat and Abdel Nasser. They both wanted to know how he came to join them. So they asked him, ‘Assassination like Sadat or poison like Nasser?’ He lowered his head and said, ‘No, Facebook.’”

Revolution is My Name also captures the close relationship between Egyptians and their military. The army has been held in high regard in Egypt ever since the 1973 war against Israel where it managed to win some strategic victories and make up for the humiliation of 1967. Prince shares this sense of respect. “I always salute the martyrs,” she writes, “as I drive past the memorial as a tribute to our soldiers who died during the October 1973 War with Israel.” But when the tanks role into Tahrir Square questions arise: “What will the army do to us? Will it like us, as we like it? Will it side with us or against us?”

The protestors, including Prince, welcome the soldiers and begin a new chant: “The army and the people are one hand.” They climb onto tanks and take selfies with the soldiers. Prince even tells us how she embarasses one soldier (who turns out to be an officer) by flirting with him. This close relationship between the protestors and the army made sense in the context of the protest. The military wished to be seen to be an apolitical institution and the protestors did not want to make an enemy of the army.

But the relationship appears to remain unaffected by the end of the protests despite the fact that the soldiers did not intervene when Mubarak’s thugs invaded Tahrir. The reputation of the army seems to be unscathed by the end of the book. While celebrating Mubarak’s downfall, Prince herself climbed up onto a tank with two soldiers. “I stood on top of the tank between them and felt proud [at Mubarak’s downfall],” she writes. “I gave my cell phone to one of the soldiers and showed him how to take a picture.” While it was Morsi’s religious authoritarianism that provoked the protests against him, the enduring nature of this close relationship between the Egyptian people and the army helps to explain why Sisi’s 2013 coup was welcomed by so many.

Revolution is My Name is an essential read for anyone who wishes to understand, not just the overthrow of Mubarak, but also the Arab Spring and the challenges that many in the Middle East face when it comes to democratisation.

William Eichler has a BA in Philosophy and Politics and an MA in Middle Eastern Studies. He is a freelance journalist and part-time English teacher who lives and works in the UK and Turkey. He blogs at Notes on the Interregnum: Essays and Reviews and you can follow him on Twitter at @EichlerEssays.

1 Comments