In In the Heat of the Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and The War on Crime, Michael W. Flamm draws on personal narratives and archival evidence to outline the development of the New York Riots of 1964 — instigated by the shooting of the fifteen-year-old black teenager, James Powell, by a white police officer — and their wider repercussions on the social and political landscapes of 1960s America. Resonating with current discussions on racism and police brutality, this book will prove an inspiring read for those questioning the relationship between discourses of law and order and the reproduction of collective fear, writes Eraldo S. Santos.

In the Heat of the Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and The War on Crime. Michael W. Flamm. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2017.

In Ferncliff Cemetery in Westchester County, New York, no plaque indicates the grave in which James Powell was buried more than half a century ago. The fifteen-year-old black teenager, entombed near African American luminaries such as James Baldwin and Malcolm X, lies forgotten, and many today have probably never heard his name. But his homicide—Powell was shot dead on 16 July 1964 by Thomas Gilligan, an off-duty white police officer—and the political events that succeeded it were responsible for significant upheaval in the Civil Rights Movement and, more broadly, in post-1960s US politics. In the Heat of the Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and The War on Crime tells us how Powell’s death triggered major civil unrest in New York, shifting the already widespread call for ‘law and order’ within US public discourse to the centre of the debate on state policies designed to fight crime.

In Ferncliff Cemetery in Westchester County, New York, no plaque indicates the grave in which James Powell was buried more than half a century ago. The fifteen-year-old black teenager, entombed near African American luminaries such as James Baldwin and Malcolm X, lies forgotten, and many today have probably never heard his name. But his homicide—Powell was shot dead on 16 July 1964 by Thomas Gilligan, an off-duty white police officer—and the political events that succeeded it were responsible for significant upheaval in the Civil Rights Movement and, more broadly, in post-1960s US politics. In the Heat of the Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and The War on Crime tells us how Powell’s death triggered major civil unrest in New York, shifting the already widespread call for ‘law and order’ within US public discourse to the centre of the debate on state policies designed to fight crime.

Michael W. Flamm is already known for his research on the US political culture of the 1960s as well as for his studies on debates between liberals and conservatives. In the Heat of the Summer continues more than two decades of reflection on this complex moment in US history. In the book, questions previously raised in Law and Order: Street Crime, Civil Unrest and the Crisis of Liberalism in the 1960s are discussed using a different and fruitful strategy. Here, Flamm elects a very precise cluster of historical events to put under scrutiny—the first ‘long, hot summer’ of the 1960s unleashed by Powell’s death—and analyses its main consequences: the beginning of ‘an age of law and order’ in US domestic politics, which would galvanise the so-called ‘War on Crime’ and the long-lasting crisis of US liberalism (286). The result is impressive. Written in a clear and accessible style, the book may be of interest not only to academic scholars working on related topics, but also to general readers interested in US and African American history.

Archival materials, biographies, memoirs, newspaper articles, official reports, interviews and correspondence with reporters, activists, officers and participating eyewitnesses: all are mobilised in order to write a day-by-day history of the New York riots of July 1964. Exploring the interstice in which history and story meet, Flamm weaves all these elements into a detailed, sometimes anecdotal, narrative. From the participants’ height, body shape and facial features, to their life stories and career aspirations, everything deserves the historian’s attention, who describes carefully the unfolding of events, taking into consideration ‘a broad range of personal perspectives—black and white, young and old, Christian and Jewish, angry and fearful as well as radical, liberal, and conservative’ (7).

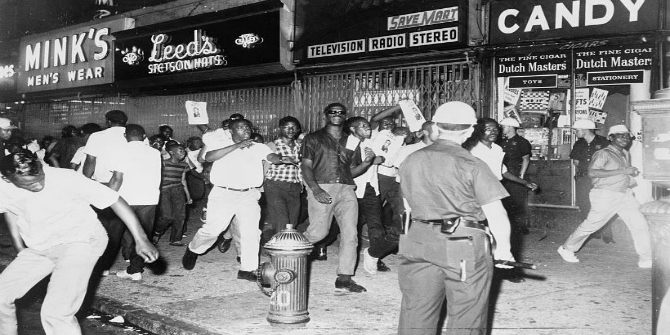

Image Credit: Demonstrators carrying photographs of Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan march on 125th Street near Seventh Avenue during the Harlem Riots of 1964 (Dick DeMarsico, New York World Telegraph & Sun, Wikipedia Public Domain)

Image Credit: Demonstrators carrying photographs of Lieutenant Thomas Gilligan march on 125th Street near Seventh Avenue during the Harlem Riots of 1964 (Dick DeMarsico, New York World Telegraph & Sun, Wikipedia Public Domain)

The book goes far beyond a simple reconstruction of the events that took place in New York between 16 and 23 July 1964, however. In Chapters One to Nine, Flamm references both the contributing factors and the political consequences of the uprisings. Flashbacks to the urbanisation in Central Harlem (Chapter Two) and Bedford-Stuyvesant (Chapter Seven) contextualise the social-economic situation in the places where civil unrest began. Chapter Two looks furthermore into previous moments of civil disorder in Harlem, such as the riots of 1935 during the Great Depression and of 1943 during World War II.

From Chapters Ten to Twelve, the narrative’s cadence accelerates. Here, the focus moves to how ‘law and order’ became a central issue during the two subsequent presidential elections: the first one won by the then-Democratic president Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964, some months after the fateful events in New York, and the second, won by Republican candidate Richard M. Nixon in November 1968. Flamm analyses the way in which, following the events of 1964, personal security and law enforcement progressively became the major concern of US citizens and how these issues were explored by both conservatives and liberals during local and presidential campaigns.

The conservative role in this important shift in focus from other domestic issues towards public safety should not be ignored, Flamm contends. By accusing the Civil Rights Movement of weakening public respect for law and authority, conservative discourse nullified the differences between nonviolent civil disobedience, civil unrest and crime, insisting that increasing crime rates were the sign of liberal governments’ failure in ensuring law compliance. The episodes of civil disorder were said to be the indication of how ‘racial integration’ and ‘permissive liberalism’ could be harmful to public safety. Liberal counter-discourse, in turn, consisted of the defence that both urban crime and civil unrest could not be understood without taking into consideration what Cleveland Robinson, a member of the New York City Commission on Human Rights, called in 1964 ‘the whole social structure’ (133): precarious housing, low-funded schools and segregated education, a lack of jobs due to automation and police brutality as well as consequent hopelessness and despair. Only an attack on these ‘root causes’ of noncompliance and unrest could enable an efficient fight against crime. The ‘War on Poverty’ declared by Johnson was said to be, in this context, the fairest and most effective way of doing so.

As Flamm shows, Johnson’s discourse still sounded convincing in 1964, when he won the election over Senator Barry Goldwater—the man who triggered in his acceptance speech to the Republican Convention the call for law and order. However, as street criminality rose over the following years despite the War on Poverty’s policies, the liberal stance lost its soundness. By mobilising anxiety provoked by increasing crime rates, conservative attacks won a new dimension: Johnson’s ‘Great Society’ programme started to be held responsible for the deviation of federal funds from issues such as public safety. The figure of the ‘undeserving poor’—associated predominantly with the urban black criminal—started to permeate the public imagination and discourse more and more, leading some sectors of the population to the conclusion that, by rewarding noncompliance, the War on Poverty led to (and did not help to defend against) more criminality. It was thanks to this scenario that Nixon’s motto could gain popularity: ‘Freedom from fear is a basic right of every American citizen’ (285). For more than fifty years, ‘law and order’ would remain the US political lingua franca, spoken by citizens of different races, classes and ideologies: a language whose syntax would offer for decades, as Flamm briefly shows in the book’s epilogue, cohesion and coherence for both parties’ discourse in their fight for power.

The focus on the liberal and conservative stances overshadows in some moments the role and importance of more radical interlocutors in debates on racial and economic injustice. More attention could be given, moreover, to the specificities of Johnson’s antipoverty programme as well as its racial implications. Such reservations do not, nonetheless, obscure the book’s merits. By exploring the tensions between aspirations for ‘social order’ and ‘social justice’ (285), it helps put the history of the freedom struggle in the US in a new light. It also offers myriad materials that can be enlightening in the context of current discussions on the new dynamics of racism, the persistence of police brutality as well as the effectiveness and fairness of state policies designed to reduce criminality. Perhaps more remarkably, it is a reminder of how putting into circulation discourses on order and personal safety are one of the most effective strategies in producing and reproducing collective fear. From Harlem to Ferguson and beyond, law and order’s heritage still haunts us. In the Heat of the Summer would prove an inspiring read for those who fight against it.

Eraldo S. Santos is a PhD candidate at University of Paris I – Panthéon-Sorbonne. His doctoral research focuses on the history of the concept of ‘civil disobedience’. He analyses how it was reformulated in the context of the revival of political obligation theories in the US during the 1960s and 1970s. The project is funded by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES, Brazil).

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.