In this author interview, we speak to Dr Noni Stacey about her new book Photography of Protest and Community: The Radical Collectives of the 1970s, which examines how London-based photographers formed collectives that engaged with local and international political protest in cities across the UK. The book surveys the radical community photography produced by Hackney Flashers Collective, Exit Photography Group, Half Moon Photography Workshop, the producers of Camerawork magazine and the community darkrooms, North Paddington Community Darkroom and Blackfriars Photography Project.

The archive of the Exit Photography Group is held at LSE Library; interested readers can find out more about the archive and the catalogue.

Q & A with Dr Noni Stacey, author of Photography of Protest and Community: The Radical Collectives of the 1970s. Lund Humphries. 2020.

Q: Your book explores the ‘community photography’ of London-based photography collectives in the 1970s. What were some of the ideas behind community photography, and how were these shaped by the social and political context of the time?

Q: Your book explores the ‘community photography’ of London-based photography collectives in the 1970s. What were some of the ideas behind community photography, and how were these shaped by the social and political context of the time?

‘Community photography’ is a phrase that sprung from the utopian aspirations of politically engaged photographers in the 1970s. Britain was in the throes of an extensive legislative programme that sought to enshrine the rights and responsibilities of citizens amid widespread struggles for equality and the re-imagination of British cities in the post-war period. As part of this push for equality, the collectives signed up to the ‘democratisation’ of photography, whereby people would take photographs of their lives to bring about change.

The phrase ‘community photography’ resonated with the networks flourishing around community activism and local political initiatives as it reflected a determination on the part of the photographers to demystify analog photography. Taking photographs in the 1970s was expensive, quite complicated and required access to a darkroom, chemical fluids, trays and printing paper.

The photographer and theorist Jo Spence wrote of the varied definitions for community photography in the magazine Camerawork, ranging from working in the community to teaching people to use cameras and print their own pictures, to a reworked definition of both photojournalism and documentary. This was about the local, spending time in the community and reflecting the community back to itself through exhibitions and talks. The political aspect to this was the belief that people would then take photographs to show how their lives were, at a time of appalling housing conditions, dangerous or precarious workplaces – and widespread inequality in terms of race and gender.

Q: You originally aimed to focus on how photography collectives enabled the transfer of photography skills to the marginalised and uninitiated, before shifting to explore the interconnections between the different collectives. What inspired the change of focus?

It became apparent during the course of my PhD research at University of the Arts London that the story was not one solely about photographers working in the community. The collectives knew of each other – and all congregated around the Half Moon Gallery and Half Moon Photography Workshop, publisher of Camerawork. These meetings took place at a time when the idea of the small, independent photography gallery was new. The major galleries and museums often looked askance at photography, believing it to be the usurper of the art world. So, being in a collective was a way of finding a place and becoming part of a ‘community of interest’: it gave photographers the opportunity to follow their interests, whether it was among the slums, dilapidated rental properties, squats and communes – all to be found just a short distance away from LSE in Islington and Hackney.

So, the intermittent attempts and projects to teach people photography did not preclude bringing the marginalised into the major political debates of the time around housing and inequality. During the course of my research the important bodies of work produced by the collectives, referencing British history and the history of photography in the 1970s, became of great interest to museums, institutions and archives. The questions about representation, race and gender persist; labour conditions, access to affordable housing, equal pay – all of these political debates that the collectives focused on – are still integral to political action and protest today.

Q: A key theme of the book is that this approach to photography raised conundrums around defining, accessing and engaging communities, as well as the question of ‘who is it for?’ How successfully did the collectives navigate these issues?

The photographers navigated their way round the barriers of class and community, and the insider/outsider position of the photographer, with varying degrees of success. It is important to remember that all of the people involved in the collectives were young, in their early twenties: they were learning about photography and finding a sense of themselves. What they did know was that the very well-known figures in photojournalism, such as Don McCullin and Philip Jones Griffiths, were inspirational and yet set apart by their success. It was very difficult for young photographers – and still is – to breach the barriers to ‘Fleet Street’, the term given to the mainstream newspapers. In the weekend colour supplement magazines, the Guardian and the Observer, The Times and The Sunday Times, the Telegraph and the Sunday Telegraph all published lavish spreads of photographic news stories from around the world, often alongside sumptuous advertisements for the churn of capitalism. The collectives militated against this practice of ‘parachuting in’ a photographer to a community to take pictures, which were then selected and edited by picture editors for publication. These photojournalists did not write the text.

Q: Given these practices, how did the collectives challenge the parameters regarding what a photographer could and could not do through their work?

Jones Griffiths served as an exemplar with his excoriating text on American military involvement in the Vietnam War, Vietnam Inc. In this he wrote the text and captions to accompany the photographs in contravention of journalistic practices. The book was sympathetic to the plight of the civilian population of Vietnam during the War. The collectives adopted this as permission to introduce their views into the texts – and work in collaboration with a network of charities, pressure groups and publications who documented marginalisation and offered solutions, such as the Child Poverty Action Group or the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. This took place away from government and often at a tangent to the Labour Party or the trade union movement.

They also took inspiration from the countercultural publications that came out of the 1960s, such as International Times and the groundbreaking call to arms for the Women’s Liberation Movement, Spare Rib. If the mainstream press wasn’t open to newcomers, then the answer was to create their own publications. Crucially, Barry Lane, the newly appointed Photography Officer at the Arts Council of Great Britain, had been inspired by a research trip to the USA and Canada, where he looked into the community photography schemes that were engaging with a broad range of people, from prisoners to schoolchildren. Lane held the purse strings and authorised grants for projects and publications. Free of constraints from advertising and the corporations that had a stranglehold on the news media, the photographers could create their own publications and exhibitions that reflected their political engagement.

The collectives were not content to simply take the photographs; they wanted a say in how they were published and exhibited. It is inspiring to see the ingenuity involved in setting up a touring programme for the handmade laminated exhibitions that came out of the collectives. Lamination was a technique the photographers borrowed from the glossy world of advertising: these exhibitions withstood the bumpy trail of Red Star parcels on then British Rail trains around the country. The collectives were London-based, but their work travelled to polytechnics, universities, libraries, community centres, laundrettes, Working Men’s Clubs, nurseries – anywhere that would have them.

Q: On that note, I was particularly interested in reading about the feminist and socialist Hackney Flashers Collective’s approach to their exhibitions, like Women and Work and Who’s Holding the Baby? How did the collectives change ideas about photographic exhibition and display?

It was not so much that the Hackney Flashers, or the other collectives, changed the site of exhibition and display; rather, they created and sought new spaces to take their politicised projects into the community. In this way, they created a new circuit for photographs. Women and Work, a groundbreaking and extensive exhibition on women working across Hackney, was partially funded by the Hackney Trades Council and exhibited at Hackney Town Hall in 1975. Thereafter, parts of the exhibition popped up in laundrettes and community centres, in the form of posters or tape slide shows and pamphlets. This was their strategy to agitate and provide a space for political unrest while provoking a sense of agency in those highlighting inequality in all its guises.

Q: What also stood out was how the collectives combined photographs, text and statistics in their work. Why did the collectives see this combination as an instrument of social change?

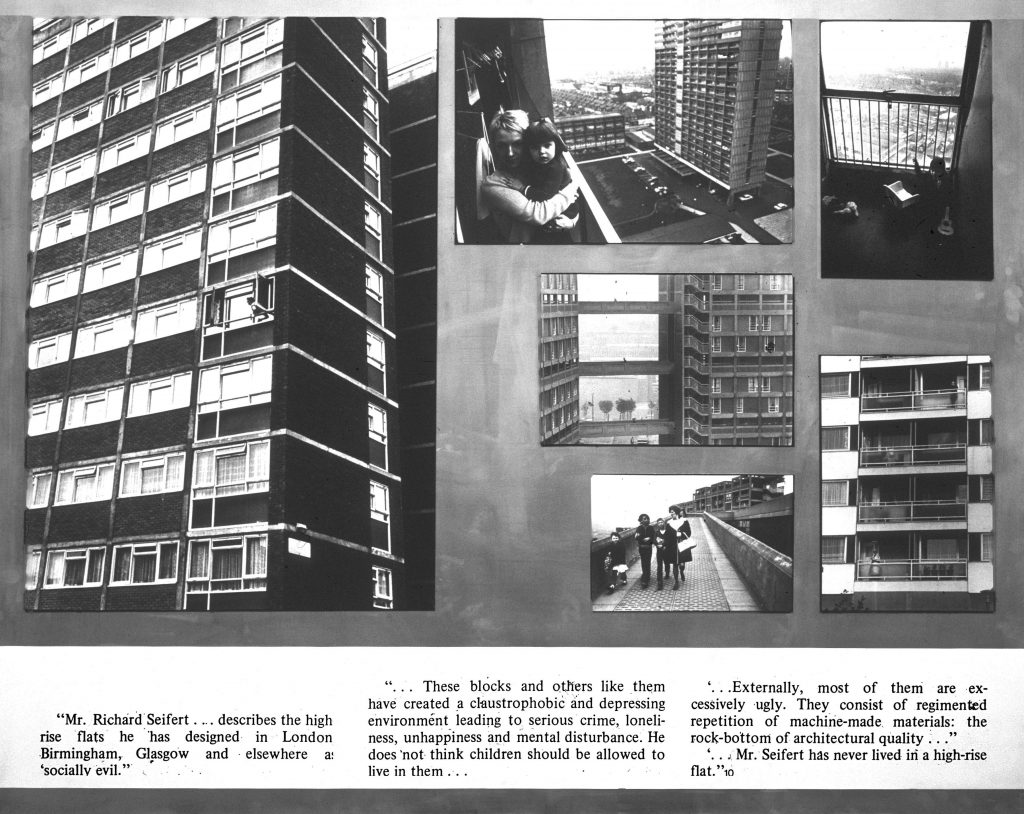

Statistics – the raw data of argument and political debate – were integral to the publications and exhibitions. This happened at a time before the internet, in a world without mobile phones and before computers – only forty or so years ago. So, how did people circulate information and statistics? They typed it up painstakingly, as often as not by women. The collectives were impelled to circulate statistics and information so that people would have access to information that was either not available or subject to manipulation for political purposes. For instance, Philip Wolmuth, instigator of the North Paddington Community Darkroom on Harrow Road, North West London, created an exhibition about housing. Within this, and alongside the photographs, he detailed the statistics and conditions for public and private housing. This was at a time when slum landlords prevailed – and the worst of public housing was infested with vermin and soiled by damp. The photographs are shocking. This was nothing less than a call to action.

Q: One of the collectives examined in the book is the Exit Photography Group, whose archive is held at LSE Library. Could you speak more about this collective?

Exit Photography Group, which became the trio of Paul Trevor, Chris Steele Perkins and Nicholas Battye, embarked on what would become a six-year project to document poverty in British cities: Belfast, Middlesbrough, Liverpool, London, Glasgow, Birmingham and Newcastle. Exit amassed the following in covering the state of British cities in the post-war period: ‘The raw material of the study consists of 797 rolls of 35 mm film (approximately 28,000 negatives) and 93 hours of taped-recordings plus other photographs taken by Exit prior to the study.’ This project took its toll on the photographers – and by the time they came to publish their book, Survival Programmes: In Britain’s Inner Cities, the political landscape had been transformed by the arrival of Margaret Thatcher as Prime Minister.

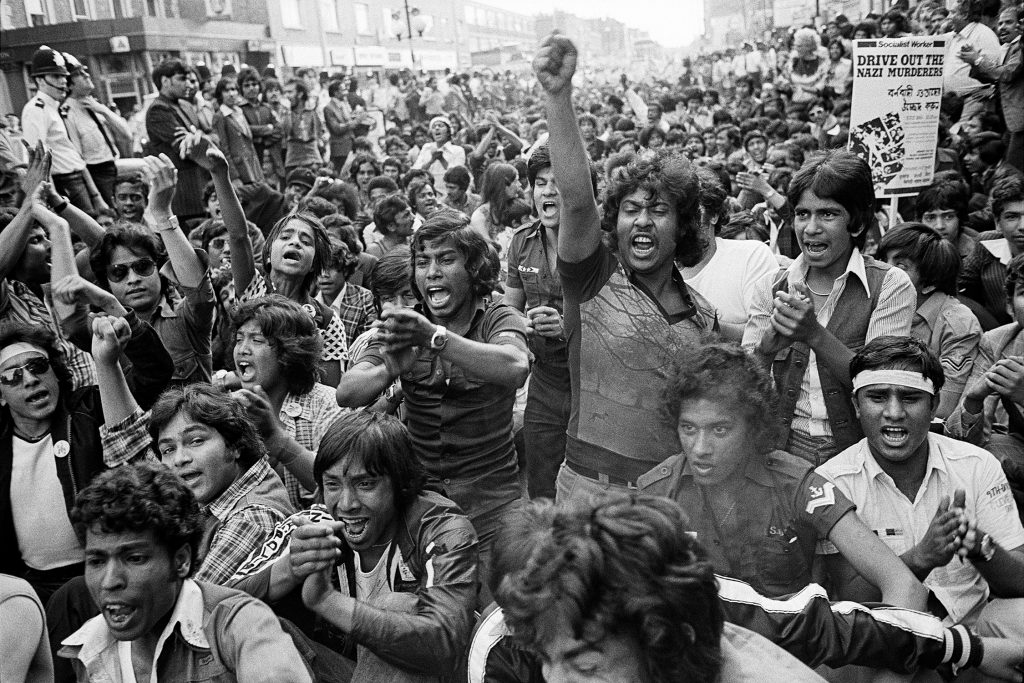

It has been fascinating to read through the whole archive for Exit Photography Group, held in LSE Library. There was a sharp contrast between the orderliness and peaceful nature of the LSE archives section and the narrative of poverty, disenfranchisement, inequality and frankly appalling living conditions that is laid bare in the archive boxes for Exit Photography Group’s book, Survival Programmes. And yet, the photographs also show a sense of resistance and evidence of a strong spirit in the face of hardship – and, most importantly, a more complex and positive image of people of colour in the 1970s. This was at a time of explicit and enduring racism, and it demonstrates the way in which the political campaigns in which Exit and the other collectives were engaged with then still resonate now.

Q: Today, the camera phone and social media have become integral to the representation and distribution of images of contemporary protest. Does this indicate the continued democratisation of photography, or do we still grapple with similar conundrums around representation, engagement, distribution and access as the 1970s collectives?

As I outlined to the publisher of my book, Lund Humphries, the work and photographs that came out of these collectives constituted a sustained political challenge. Today, there is much talk of social and cultural engagement – yet this is an anodyne and in many ways amorphous space. The collectives were immersed in the political events and struggles of the day – often bitterly fought – around equality in terms of gender, race, work and housing. The exhibitions and publications that came out of the collectives bristled with political data and sociological analysis. They evoked and emulated the protests of the Civil Rights Movement, protests at US involvement in the Vietnam War and those of the Women’s Liberation Movement.

Moreover, the collectives challenged institutional structures, in particular the gallery network. Now the work of the collectives is governed by funding sources – which are anathema to overt political discourse – and by its entry into the gallery network, one of the most conservative labour structures in existence. Often permanent curators, tenured academics and cultural producers have a job for life, the latter buoyed by funding which is open to few. This is in no way reflective of the general workforce in either the arts, academia or elsewhere, where many people are employed on short-term or zero hours contracts, or those who are out of work with no prospect of re-entering the workforce any time soon.

The idea that the camera phone is accessible to all – or computers are available to everyone – is a sop. If you take a photograph and put it on social media – who will look at it? What agency does this producer really have? I don’t think that there is greater democratisation of the media today. When you see that the all-powerful corporations that own social media harvest photographs and data for economic gain – where is the democracy in that? Major newspapers and television news stations in the UK are still owned by media dynasties with their own narrow political agendas.

The way in which photography has been circulated by and about the Black Lives Matter movement this year demonstrates the problems around representation: namely, who took the photographs? Have they been edited? Who wrote the accompanying text? Is it the truth? These questions abound, and they illustrate that strong editorial guidelines in journalism are essential. The concomitant concern is the diversity (or otherwise) of people working in the media. All of these issues are current and ongoing.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The interview was conducted by Dr Rosemary Deller, Managing Editor of the LSE Review of Books blog.

Thank you to Dr Noni Stacey and to all the photographers whose work is included in this interview for enabling the use of the photographs in this post. Permission to reproduce these photographs should be sought from the copyright holders.

1 Comments