In In Fading Light: The Films of the Amber Collective, James Leggott offers the first full-length scholarly study of the films produced by the Amber Film & Photography Collective through over five decades of engagement with the working-class communities of North East England. This is a valuable and insightful contribution to a neglected area of British film history, writes Tom Draper, that will hopefully inspire further work building on this foundational text.

In Fading Light: The Films of the Amber Collective. James Leggott. Berghahn Books. 2020.

The Amber Film & Photography Collective first came together as a meeting of like-minded film students at Regent Street Polytechnic in 1968. Spurred on by the efforts of founder-member Murray Martin, the group soon departed the capital for Newcastle upon Tyne, kick-starting what has become more than five decades of engagement with the working-class communities of North East England. Despite earning plaudits at international film festivals and receiving support from Channel Four throughout the 1980s, there remains a sense that Amber’s contribution to British film history has been underappreciated. James Leggott’s In Fading Light: The Films of the Amber Collective, the first full-length scholarly survey of their films, aspires to offer a corrective to this lack of recognition. This welcome book aims to ‘heighten the collective’s standing within international film culture, and thereby encourage further viewing and discussion of this remarkable body of work’.

The Amber Film & Photography Collective first came together as a meeting of like-minded film students at Regent Street Polytechnic in 1968. Spurred on by the efforts of founder-member Murray Martin, the group soon departed the capital for Newcastle upon Tyne, kick-starting what has become more than five decades of engagement with the working-class communities of North East England. Despite earning plaudits at international film festivals and receiving support from Channel Four throughout the 1980s, there remains a sense that Amber’s contribution to British film history has been underappreciated. James Leggott’s In Fading Light: The Films of the Amber Collective, the first full-length scholarly survey of their films, aspires to offer a corrective to this lack of recognition. This welcome book aims to ‘heighten the collective’s standing within international film culture, and thereby encourage further viewing and discussion of this remarkable body of work’.

Amber’s multifaceted legacy has attracted a range of scholarly approaches. Significant work has been done on the collective’s radical practices and unique egalitarian wage structure, participatory-based decision-making and vertical integration model. Amber’s ‘early manifesto for an ideas factory’ (‘Integrate life and work and friendship. Don’t tie yourself to institutions. Live cheaply and you’ll remain free. And, then, do whatever it is that gets you up in the morning’) has appealed particularly to sociologists. Less attention has, however, been placed on the films themselves. Leggott’s objective is to give ‘the unfamiliar reader an entry point into a body of work that is potentially intimidating in its range and diversity’. The task is to trace the threads which run through 50 years of documentaries and dramas, and explore the shifting concerns provoked by changing historical circumstances.

If there is a grand narrative which structures Amber’s work, it is the North East’s troubled economic history: deindustrialisation and decline, struggle and hardship, deprivation and poverty – recurrent concerns which may account for their obscurity. ‘The question remains of whether Amber have flown beneath the cultural and critical radar, willingly or otherwise, as a result of being perceived as “regional’’,’ writes Leggott. Or from another perspective: ‘it is easy to imagine how a casual observer of Amber’s work and reputation might align it within the apparently regressive school of “northern realism’’.’

Such readings usually bring the attendant charges of nostalgia, romance and parochialism: criticisms which have dogged the collective over the decades. In Fading Light wants to move past such easy judgements. Leggott’s in-depth analysis of individual films demonstrates that there is more to Amber than a mere celebratory nostalgia for a bygone age. The collective’s sustained experimentation with the form of documentary and drama, and ‘commitment to authentic and responsible representation of people, places and experiences’, warrant detailed critical engagement and scholarly interest.

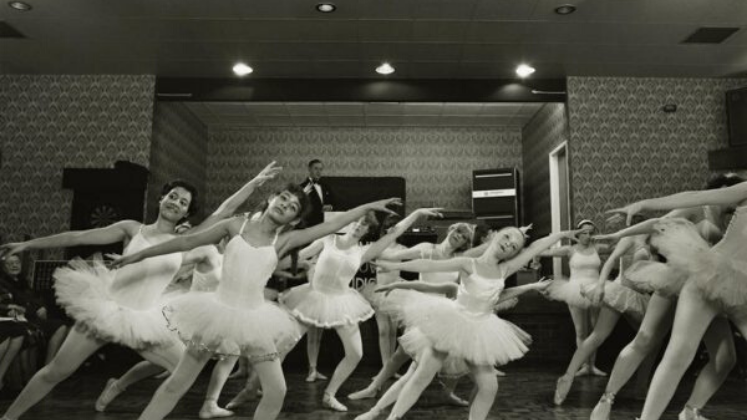

Image Credit: Photography from ‘Step by Step’ collection (1980-1989), exploring mother-daughter relationships through a dancing school in North Shields, REF: 059-001-LBW (© Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen courtesy of Amber CC BY NC ND).

Since Amber’s back catalogue offers ‘a simultaneous sense of coherence and idiosyncrasy’, Leggott believes that it is appropriate to discuss the work through the lens of auteurism. This might seem to ‘undermine the claims made elsewhere for Amber’s non-hierarchical, collectivist identity’, but enough commonality of purpose is found in the collective’s work to justify such an approach. Their ‘commitment to being credited, on screen and in promotional discourse as a collective’ has arguably been another obstacle to recognition. Amber’s members have themselves acknowledged that their ‘“old fashioned” policy of collectivism has bamboozled critics and left them in “marketing limbo’’.’ The elevation of a figurehead would likely help to improve the collective’s standing. Murray Martin is usually proposed as such a candidate. Leggott, however, devotes a whole chapter to the films of Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen. The rest of Amber’s work is discussed collectively.

In Fading Light divides Amber’s history into distinct periods. Leggott’s method is broadly chronological and yet there is space to discuss the thematic bonds shared by individual films. ‘The number of cross-references I give between films, and across chapters, is testimony to the manner in which many productions have developed organically out of, or in tandem with, other projects,’ he writes. Amber’s first decade constitutes an ‘apprentice period’, in which craft skills are acquired and the concerns which will animate the next four decades of output are identified. This includes a commitment to oppositional politics and a recording of changing working-class communities, an interest in the impact of structural economic forces on individual lives and an experimentation with both documentary and dramatic impulses. Amber’s early short documentaries predominately focus on traditional industries in decline, the lost worlds of shipbuilding, coal mining and glass production ‘salvaged’ by the filmmakers.

The 1980s through to the early 1990s were one of Amber’s most prolific periods. Leggott devotes three chapters, the bulk of the book, to this moment in Amber’s history, citing ‘the sheer range of experimentation’ and ‘intense flowering of ideas, commitments and, at times, some very personal preoccupations’. The financial security supplied by Channel Four enabled the collective to pursue several different trajectories. The Current Affairs Unit (1983-87), a ‘means to develop film and photographic work in quick response to local and current issues’, culminated in the release of T. Dan Smith (1987), ‘one of the most singular and ambitious documentaries of the 1980s’, and From Marks & Spencer to Marx and Engels (1989); two films given ample coverage in the book. Konttinen’s Byker (1983), Keeping Time (1983), The Writing in the Sand (1991) and Letters to Katja (1994), deeply personal works grounded in her photographic process, shifted Amber’s focus from the working world of men towards leisure and the feminine sphere, while dramatic features such as Seacoal (1985), In Fading Light (1988) and Dream On (1991) eschewed the experimental programme of the films above. They are among Amber’s most accessible and recognisable films and fit ‘relatively comfortably within the tradition of British social realist cinema’.

Subsequent decades would bring a turn to the periphery, towards the former mining communities of East Durham whose struggles are recorded in four dramatic features, as well as a retrospective look at the collective’s own history. It is telling that Amber have recently engaged in the type of contextualisation and analysis of the past usually conducted by independent film critics and historians. Scholarly distance allows Leggott to discuss some of the criticisms absent from Amber’s own publications and historical short documentaries, despite his desire to support and celebrate their achievement. This book has introduced several lines of inquiry which will surely intrigue scholars working on the visual representation of the North. In Fading Light offers a valuable and insightful contribution to what has been a neglected area of British film history. The hope is that further work will build upon this foundational text.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Banner Image Credit: Kendal Street, Byker, 1969. REF: 032-001-LBW (© Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen courtesy of Amber CC BY NC ND).