Only a ‘tiny minority’ is affected by benefit sanctions, according to the government. This claim relies on weak data, writes Sumi Rabindrakumar. She looks at the data for single parent sanctions and explains why the risk is not only far greater than suggested, but has also increased compared to a decade ago. So although the government has resisted a full review of the sanctions system, the data suggests this is long overdue.

Only a ‘tiny minority’ is affected by benefit sanctions, according to the government. This claim relies on weak data, writes Sumi Rabindrakumar. She looks at the data for single parent sanctions and explains why the risk is not only far greater than suggested, but has also increased compared to a decade ago. So although the government has resisted a full review of the sanctions system, the data suggests this is long overdue.

The government maintains the risk of benefit sanctions is very low, and that it affects a ‘tiny minority’ of claimants. However, this interpretation relies on a peculiar understanding of risk. It focuses on a monthly rate, rather than looking at the risk over a longer period of time (most people claim Jobbseeker’s Allowance for longer than a month).

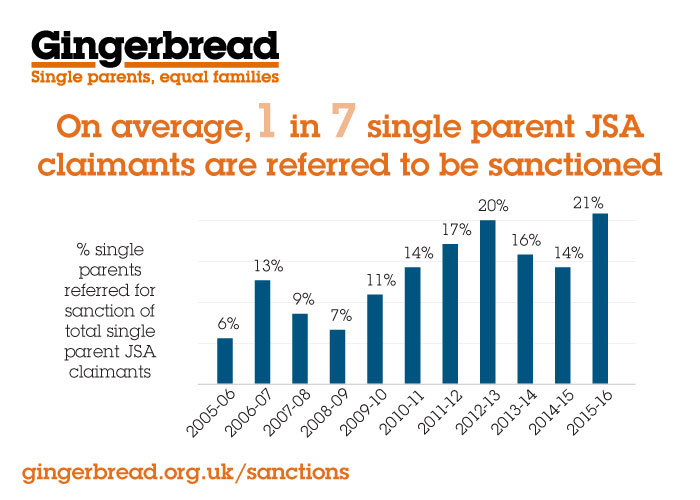

This approach isn’t a dry statistical curiosity: it is fundamental to understanding the extent of sanctions. And as new research from Gingerbread shows, it results in a remarkable underestimate of the actual risk. The new analysis finds that around one in seven single parents receiving Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA) were sanctioned in a single year. That’s over twice the 6 per cent rate the DWP has previously quoted.

In fact, at its recent peak, around one in five single parents were referred for sanction. This is particularly worrying as, even if some of those are dismissed before a sanction is imposed, this indicates a much more widespread reach of the process than previously known. Just being referred for a sanction drags single parents into the administrative burden of warning letters, phone calls, and evidence-gathering to defend themselves.

Beyond this, the data portrays a picture of both change and continuity. The risk of a sanction referral (and having one imposed) has increased compared to a decade ago – up from around 10 per cent and 4-6 per cent respectively. The data also reflects a tightening sanctions regime. Once single parents are referred for a sanction, they’re more likely to end up having one imposed than before. Low-level sanctions are also much more likely now than before – in just two years, they jumped from six in ten single parent sanctions in 2013/14 to around nine in ten single parent sanctions in 2015/16.

At the same time, single parents continue to be more likely to face unfair sanctions than other claimants. Overall, around one in five single parent JSA sanctions gets overturned. This is higher than the overturn rate for other claimants; however, single parents also more likely to challenge their decisions. Yet even when we look at formal challenges – so, all things being equal – there are still differences. 62 per cent of formal challenges are successful for single parents, compared with 53 per cent for other claimants.

Pulling this data together raises worrying questions for sanctions policy. In the absence of any evidence that claimant behaviour has changed, why are sanction rates going up? What is driving the increased use of low-level sanctions? And why are single parents still more likely to be unfairly sanctioned than others?

But there is also a more fundamental question regarding the system that still needs to be answered: is this policy working? This is a question that has long been ducked, by both the coalition and present governments. This might well be because they cannot answer – as the NAO recently pointed out, the DWP knows little about the impact of its sanctions policy.

From Gingerbread’s experience, the signs don’t look good. Sanctions are intended to ensure those receiving benefits comply with the rules. Yet too often sanctions are applied despite claimants fully intending to seek work – whether that’s arriving slightly late for an appointment when childcare falls through, or not applying for an inflexible job because the school drop-off and pick-up would be unmanageable.

Sanctions, as part of the system of conditions attached to receiving benefits, are also intended to get people into work. There are growing concerns as to whether the financial losses incurred help as intended. At their worst, they risk pushing families into poverty and further away from work. When child poverty in single parents is on the rise, this is particularly worrying.

We are at a crossroads for sanctions policy. The government has started to set out a new approach to help out of work families. It is also due to respond to the Public Accounts Committee inquiry on benefit sanctions. And the reach of sanctions policy is set to extend much further under universal credit, with the extension of job-seeking rules to parents of three- and four-year-olds last week and anticipated conditions for low-paid working families to increase their earnings or hours.

What better time for government to show it is genuinely committed to better support for unemployed families and an effective use of public money, and properly review the use and impact of sanctions?

_____

Sumi Rabindrakumar is Research Officer at the charity Gingerbread, the national charity for single parent families. Gingerbread’s research covers a range of policy areas relating to single parent life, including childcare, employment support, welfare reform and child maintenance. Sumi tweets alongside the Gingerbread policy team @GingerbreadPA.

Sumi Rabindrakumar is Research Officer at the charity Gingerbread, the national charity for single parent families. Gingerbread’s research covers a range of policy areas relating to single parent life, including childcare, employment support, welfare reform and child maintenance. Sumi tweets alongside the Gingerbread policy team @GingerbreadPA.

Sorry but I don’t agree having been a single parent my self through no fault of my own I Brought my children up on my own to be decent honest adults all have Jobs in fact my eldest is a captain in the British army , People split up for many reasons and most of them didn’t expect it to happen if you found a partner that you stayed with then good for you , In my case the man I married was a bully who beat the living day lights out of me because he could, In other cases partners may of died or been killed due to war or ill health what ever the reason couples don’t stay together it does not give the state the right to withdraw food from anyone that is a basic right no matter what your situation , Our Government has twice been accused of systematic abuse of it’s people by the United Nations and chose to completely ignore them and anyone who condones that is a disgrace , It shouldn’t happen not ever but more so in the 5 richest country in the world shocking .

An interesting piece of work, but can I suggest a couple of reason why the state should incentive having children in stable couple relationships and for couples to stay together to raise the children:

(1) In fiscal terms, single parent relationships are more costly for the state whatever the working arrangements of the parents. Whatever your view of state spending, this is potentially revenue that could be spent on, for example, increased spending on mental health services or lower taxes.

(2) ‘while the evidence seems to be patchy and complicated, the evidence seems to support the view that outcomes are better for children raised in couples, especially for boys. While some evidence suggests that single parenthood does not tend to produced worse child outcomes relative to couple parenting once income is controlled for, it might be considered reasonable to include single parenthood as a cause of the low income.

While the state should be non-judgemental about family arrangements, it might seems reasonable to encourage changes in behaviour so that parents and potential parents select good potential parents they get along with and stay in stable couple relationships. I think that this doesn’t happen now.

Having said that, I don’t think there is good evidence that the tax and benefit changes will lead to changes in behaving around parenting.